The shadows are getting longer on Georg-Coch-Platz in Vienna’s first district, and every table outside Cafe Ministerium is full. A group of about 30 people have settled there with palpable trepidation ahead of the rest of their evening: two hours of conversation – not small talk – with a total stranger.

For one of them, that stranger will be me.

The Austrian capital prides itself on its kaffeehauskultur, established over hundreds of years of talking, reading and thinking over an unhurried melange in one of its 100-odd traditional coffee shops. Even some of the original 19th-century institutions remain operational, oases of gemütlichkeit (the German word for warmth, friendliness and good cheer) in Vienna today.

But the associated culture of open-minded, intellectual discussion has suffered from the greater demands on people’s time and attention of the modern age. Like many cities over a certain size, Vienna can be a siloed, even lonely place. One resident, Eugene Quinn, is trying to open it up.

Since March 2013 Quinn has hosted a monthly meetup at a coffeehouse in the city, pairing residents and outsiders for an evening of traditional food, drink and challenging one-on-one conversation. The premise is like speed dating, except participants spend the whole two hours with the same person, forcing them to push past small talk, and there’s no explicit matchmaking intent – though, Quinn says, it has resulted in three marriages.

That is no surprise when everything about the event is geared to foster intimacy between strangers. After a brief introduction, Quinn pairs a Viennese local with a visitor or resident expat, with no other guiding principle than trying to match participants with someone as different to them as possible – by age, sexuality, politics, gender or culture.

“The coffeehouses in Vienna have this lovely intimacy – an old-school, grand quality, which is designed for encouraging conversation,” he says. “That gets you over the first hurdle, but the first few minutes with a stranger are odd – you wonder why you’ve been chosen to sit with that person.”

To help them past that initial awkwardness, each couple is provided with a “conversation menu” of about 30 questions designed to steer the discussion out of the shallows and into uncharted depths – about money, childhood, fears, the future. For instance: which parts of your life were a waste of time? What do you need that money cannot buy? What have you rebelled against in the past – and what are you rebelling against now?

Quinn says the questions are “scandalous” – so personal and probing, you might think twice about asking them of a partner or close friend (though you should, he adds). But it feels somehow permissible to launch into them with a stranger when they’re written down. “Some people don’t answer any of the questions on the menu and some people spend two hours on one. That’s fine – it’s not a test – but they do take you to another place, and give you the confidence to cross the line of trivia.”

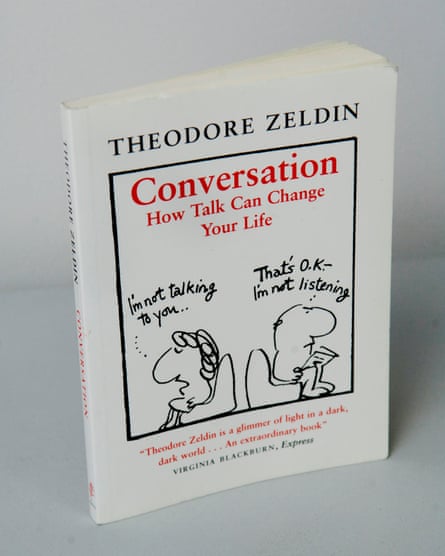

Quinn’s monthly Coffeehouse Conversations adapt the “conversation meal” concept pioneered by the British historian and philosopher Theodore Zeldin at Oxford University, who sought to connect strangers “starved of conversation which is not just superficial chat, or gossip ... or shop talk”.

Zeldin has long rallied to restructure conversation as an exercise in vulnerability and an exchange of self-revelation, forging a foundation for mutual trust. As he sees it, “conversation doesn’t just reshuffle the cards: it creates new cards, and it involves being willing to emerge a slightly different person.”

Since 2001, the Oxford Muse foundation has sought to put Zeldin’s ideas into practice, staging conversation meals at festivals, conferences and even private dinner parties in cities around the world, including Beijing, Delhi, Istanbul, Paris, London and Montreal. Zeldin singles out one held last summer in Turin’s largest church, the only available space to accommodate all 800 people who wanted to come: “They filled the semi-darkness with an extraordinary hum.”

Quinn brought Zeldin’s tischgespräche, or “table talk”, to the German-speaking world for the first time in April 2012 as part of a festival in Vienna organised by Space and Place, the non-profit organisation he cofounded. It aims to reveal a different side of the city to its residents, whether it be through an “Ugly Vienna” walking tour or staging the Austrian citizenship test as a pub quiz. “We tickle Vienna and kind of play with it a bit,” says Quinn. “We don’t take it so seriously. The city needs that – it can be over-intellectual.”

Since he began holding monthly Coffeehouse Conversations, visitors from 68 countries have taken part, and many make a point of returning. The TripAdvisor reviews are rapturous: “Who would have thought that you could spend an amazing evening among total strangers?” reads one.

But as an organiser it can be hard to get the balance of visitors and Viennese right, Quinn concedes. There tend to be more locals, and more women: “Just to generalise, men seem to be less comfortable in conversations about experience and life story – which is a shame.”

Quinn moved to Vienna from London nine years ago to join his Austrian partner. He says he now feels more passionately about Vienna than his wife does, raving about its quality of life – last week cemented by the Economist Intelligence Unit as the best in the world. But at first, he says, he found it stiff, formal and “slightly unforgiving”. Though Vienna receives millions of visitors every year, its popularity as a global conference destination means many see only its airport and hotels, and there are few organic opportunities to connect with residents. “If you wander into a pub in Dublin or a diner in America, you’ll be able to meet locals quite quickly – in a coffeehouse in Vienna, not so much,” says Quinn. “People don’t drift into each other’s worlds.”

The Coffeehouse Conversations are an opportunity to enter those other worlds, if only for a few hours. “People really do dive into very intimate and private ideas, partly because they might not see each other again,” says Quinn. “Sometimes the dialogue does continue, and people email each other weeks later, saying they’ve just thought of an answer to that question.”

It is testament to the trust built up over two hours, the reciprocal frankness and goodwill, that near the evening’s end I feel comfortable telling my partner a slightly risqué anecdote – one of my favourites – that I’d previously only shared with old or close friends. It goes down well, I think.

We part ways warmly, and she emails me the following week to thank me for “a surprisingly nice summer evening in Vienna”. We hadn’t opened the conversation menu once.

- Dates of upcoming Coffeehouse Conversations in Vienna can be found on Space and Place’s website. There will be a similar event on 2 October at the Rothen Baum gallery, Hamburg

- Groups interested in organising a Conversation Meal can contact the Oxford Muse

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion