Modern articles about how women have traditionally been portrayed throughout folklore abound; from fairy tales and folktales, to myth and legend, we all know that older women are ugly, evil, and probably a witch who eats children by luring them with candy, or traps helpless young ladies in towers. It follows that women with any sort of power or self-confidence that doesn’t stem from their purity and dainty manner must also be witches – like Snow White’s step-mother – or at least have the innate need to bump off a princess or four. Through myth, fairy tale and legend, powerful women are depicted as dark, cruel and calculating, and they are often naturally associated with winter – a season where all warmth withdraws, and the land is covered with snow and ice, and life is no more than a battle of survival against the elements. This is the place of the winter witch; the realm where the snow queens rule, and all cower in their presence – like C.S. Lewis’ Edmund cowered at the feet of the White Witch, after she had tempted him with the sweetness of Turkish delight, and coldly calculated how to hold the land of Narnia within her icy grasp. So scroll on, dear reader, to learn about the snow queens and ice princesses of old, in all of their frosty glory. Listen well for the tinkling of bells in the distance, of course, that might be drawing closer, as the winter hags watch on from shadowy corners, cackling with glee into the darkness…

La Befana, the Italian Christmas Witch

One of the most famous winter witches is La Befana, who visits Italian children at Epiphany, on January 6th. This day marks the Wise Men’s visit to the baby Jesus, and the bestowing of their gifts. Befana, the Christmas Witch, rides her broomstick through the night to deliver presents to well-behaved children, and coal to naughty little blighters who deserve no more. Want to attract the old witch to your domicile this year? Just leave out a little tipple of wine, and a good old sausage, and she’s sure to pop round.

Here’s the #LaBefana #finishline at the #epiphany #regatta in #Venice … Brilliant! ? #venicelife #Venezia #Italia pic.twitter.com/KqvxKMyQqk

— Dee Dee Chainey (@DeeDeeChainey) 8 January 2018

Babushka

While I hear yells from the back of, ‘What about Babushka, Befana’s Russian equivalent?’, I take no pleasure in stripping away these childish illusions, bestowed on many good-natured British school children in the assembly halls of old: I’m reliably informed by the epic Daria Kulesh that Russian school children know of no such figure – and from a little research, it would appear that this is true. Babushka in the Russian tongue means nothing more than ‘old woman’ or ‘grandmother’. An early mention of the name Babouscka appears in 1915, in an American book of collected tales, Little Folks’ Christmas Stories and Plays, with a brief outline of the tale – probably inspired by the Befana story, and possibly drawing on the Russian figure of Baba Yaga. Later, the infamous childhood story is developed as an American literary tale by Ruth Robbins, illustrated by Nicolas Sidjakov, and published by Parnassus Press in the 1960s no less. Still, it’s a wonderful tale that tells how the Three Kings stayed with Babushka overnight. She refused their invitation to join them on their journey, yet later regretted this. She set out on her own journey to catch up with them and visit the child Jesus, yet never fulfilled this wish, and wanders the earth still. As she does, she leaves gifts for all the children of the world in her search. Be sure to know your folklore from your fakelore this winter folks!

Snegurochka: The Russian Snow Maiden

Though be not disappointed, dear readers: Russian tradition does give us Snegurochka – no less magical, albeit with fewer wrinkles. While Snegurochka’s roots in Slavic mythology are elusive, we see whispers of this figure in Russian folk tales about a girl who is made from snow, yet soon takes on a life of her own, a tale of type 703* in Aarne-Thompson ‘s classification: the Snow Maiden.

She is mentioned in a 1868 literary fairy tale from Alexander Afanasyev’s second volume of his work, The Poetic Outlook on Nature by the Slavs, but soon comes into her own in, Snegurochka, a play by Alexander Ostrovsky a few years later in 1873, and then an opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, The Snow Maiden: A Spring Fairy Tale. She is the daughter of Grandfather Frost and Spring-Beauty, and pines to live with normal people, yet still does not have the ability to feel love herself. When her mother bestows this gift upon her in pity, the girl warms and falls in love, but soon melts as a result of this and is no more. A version of the tale from Slavonik Fairy Tales (1874), ‘The Snow Child’, retold later by Andrew Lang in The Yellow Fairy Book, recounts how an old couple long for a child. They make a little girl out of snow, which became a real, living child who grew and grew by the hour and had flesh as white as snow – called a Snyegurka, meaning ‘snow-child’. Yet fate is cruel. The girl soon melts when she jumps over a fire in the St John’s Day rites, and becomes a white cloud that floats away into the sky forever. In later stories, the girl develops into the granddaughter of Old Father Frost, or Ded Moroz, and becomes the equivalent of a Santa’s helper. Clad in white fur, with hair and skin as pale as the snow itself, she acts as his assistant in all things. By 1935, Snegurochka was accepted as a common part of Father Frost tale, and just a year later her part in the story was sealed on New Year 1937, when she appeared in the story along with her grandfather at the New Year matinee in the prestigious Moscow House of the Unions. Since then, this fairytale snow maiden has inspired music and films alike to this day:

Mother Holda and Frau Perchta

This ‘cool’ old lady (excuse the pun) takes many forms, and is known by many names. She is Berchte and Berchta in some regions, thought to be the leader of elves, and Grimm says a goddess of earth and weaving. In Swabia and Slovakia she is known as Frau Faste, the lady of the ember days – a time for fasting and prayer. Her most well-known form is as Frau Holle in the regions of Hesse and Thuringia to the north-east of Frankfurt in Germany – anglicized as Mother Holda – with ‘tumbled hair’ or a ‘tangled distaff’ for spinning, she is called a witch by Grimm, and appears in the brother’s tale of the same name. In this story, she is famous for rewarding two sisters with exactly what they deserve: the hard-working sister is showered with gold which covers her skin, while the lazy sister gets nothing more than a kettle of pitch emptied right over her head! Incidentally, of course, the hard-working sister was said to be pretty, while the lazy one ugly. It’s thought that Mother Holda brought snow to the earth each winter when feathers flew into the air as she made her bed. In Harz, she is a wizened old crone with a hunched back, and can make herself large or small at will.

In Alpine regions, Frau Perchta or Perahta (meaning ‘bright’ or ‘shining’) can either be young, pale and beautiful, or an elderly hag, with one large foot – some say that of a goose or duck. While a few people blame the size on using a trestle in spinning, in actual fact early accounts say that depictions of this strange animalistic foot do pre-date the introduction of the trestle, hence can’t be the reason at all… Some link her associations of spinning with an ability to control the fates of the world, and even say she has roots in an old winter goddess; yet what we do know for sure is that she originally acted as an enforcer of social taboos. She would check that each maiden had spun her allotted portion of flax for the year in wintertime, used as a punishment against a lazy approach to spinning work, and a warning against spinning on holy days. She soon developed into an entirely different kind of punisher: Perchta visits homes during the twelve days of Christmas, rewarding good children and servants with a silver coin in their shoe, yet slitting the bellies of uncouth little brats, removing their innards and stuffing them full of old straw and stones for their trouble. In the Middle Ages, folk would leave out food for the figure in return for good fortune, and some still leave out a bowl of porridge today. It was said that anyone eating a morsel of food, other than the allowed fish and gruel on her feast day, would have their bellies split in two. Charming.

In some Alpine regions today, people still dress up as Perchta, accompanied by a brood of animal-masked perchten, they trail through the snow ringing bells in a Krampus-like fashion in the perchtenlauf, or processions, around mid-winter through to Epiphany, and today in Fastnacht carnival parades early in the year. Many call her ‘guardian of the beasts’.

In some areas, for instance Upper Franconia, people dressed as ‘Eisen-berta’, and other versions of this winter hag, and would give candy and nuts to good children, yet hit at naughty ones with a rod, all the while swinging their cow bell! Grimm tells is that Dame Holle also rides after the hunter – presumably in the wild hunt, as do Perchta and her other embodiments – leaving a whirlwind in her wake, and anyone who sees her in this procession will either go mad or blind.

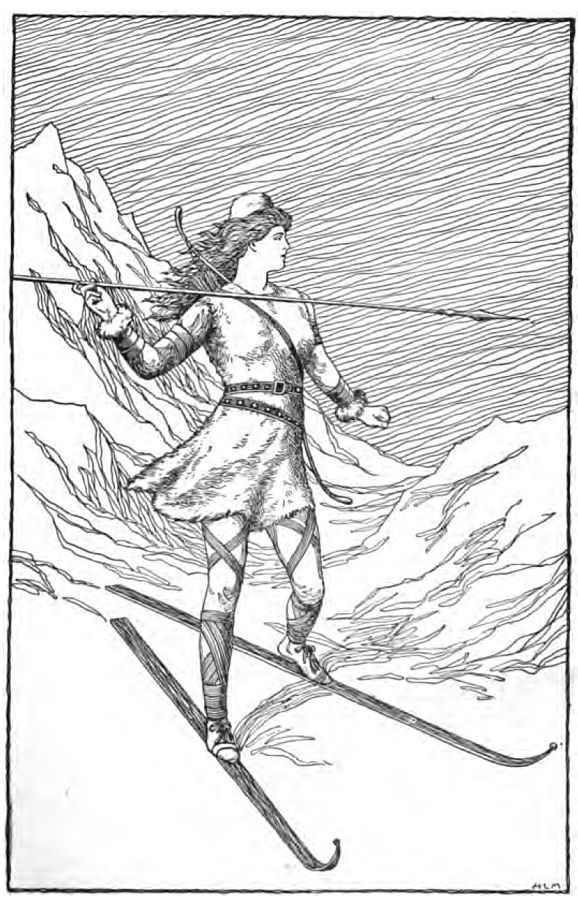

Skadi

While many people question Perchta and Holle originating from a winter goddess, other goddesses of snow and winter are not uncommon. Skaði, or Skadi, is one of the most famous, coming from Norse myth and mentioned in both the Prose and Poetic Eddas. In Viking myth, Skadi was a jötunn, often thought of as a race of giants who lived as counterparts to the gods. As a goddess she is associated with winter and snow, and like other jötunn she is associated with cold and darkness. Her home is in the mountains, where the snow never melts. She hunts with her bow, and is renowned for being clad in either snowshoes or skis, and often linked to the skiing god Ullr because of this.

Her somewhat sad tale begins when her father, the giant Thiazi, was killed by the Æsir gods in pursuit of Loki. Skadi set out to gain vengeance, yet was placated by the gods. They offered to place her father’s eyes as stars in the night sky, and said that she could choose any husband from their kind, yet with one condition: she could only look at their feet before choosing. Being a little sweet on the infamously handsome Baldr, she agreed, thinking she would be able to tell his feet from the others easily! Yet it turned out that this was not the case: much to her dismay, she instead chose the feet of the sea god Njord, due to his dazzling tootsies. The offer was binding, and she took the salty gent as her husband. As you might expect, things ended badly. The newlyweds decided to split their time between Skadi’s home in the snowy mountains, and Njord’s coastal abode. In the end, Njord couldn’t take the howling of the mountain wolves after just nine nights, so they moved to the sea. However, Skadi couldn’t sleep with the screeching of the coastal gulls. The ill-fated couple decided to call it quits, and each returned to their own home. Skadi also played a role in the torturing of Loki, setting a venomous snake above his face while he was bound, as payback for his part in her father’s death.

Certain scholars suggest that Skadi might be a deity from the north of the country, as she has attributes linked to the Sami way of life, like skiing and hunting. Because of this, she also has links to the völvur, or witches, who practiced a form of magic called seiðr during the Viking age, a skill mainly used by women, and linked to the shamanic practices of the Sami.

The Snow Queen

Some suggest that certain historical figures had reputations varnished with remnants of Skadi and the Finnish witch Louhi, in an attempt to tarnish them with the stereotype of evil northern women dealing in dark magic, a trope perpetuated for centuries, grounded in racism and propaganda against both indigenous peoples and unpopular women alike, in an attempt to slander and discredit; in any case, we see yet more examples of self-assured women being cast as evil and murderous. One example here is the Viking Queen Gunnhild – an evil sorceress raised by ‘Finnar wizards’ (the shamans of the indigenous peoples of Finland and northern Norway) and schooled in secret dark magic and witchcraft. Some speak of links between all of these figures and Hans Christian Andersen’s enchanting fairy tale, ‘The Snow Queen’, as they all contain elements of evil witches, linked to snow and ice, hailing from the north. Here’s a fabulous reading of Andersen’s famous winter tale:

Gryla, the Monstrous Giant of Scandinavian Tradition

Talking of Scandinavian giants, Gryla is a monstrous ogress who wins a firm place on this list of wintry women. A giant troll, with many tails and sporting hooves instead of feet, she has an insatiable hunger for human flesh. Her favourite meal? You guessed it: naughty little children. In fact, she makes a seasonal delicacy by trundling down her mountain each Christmas Eve to collect her fill of local little ones. Finger-licking good – literally. She’s also the mother of the infamous Yule Lads: mischievous trolls who play pranks in the lead up to Christmas, with one appearing each day to hail the big day.

Down comes Gryla from the mountains,

With forty tails,

Bag on back,

Sword in hand;

Comes to cut out the stomachs of the children

Who are crying for meat in Lent.

— Rhyme from the Faroes in the 1940s

Oshiroi Baba, the Japanese Face Powder Hag

Similarly descending from the mountains in winter are the oshiroi baba, snow hags of Japanese folklore. They are often called the ‘Face Powder Hag’, after their white face make-up like that worn by geisha and maiko. Said to be the servants of the Goddess of Cosmetics, they sport tattered kimonos and drag mirrors behind them, descending from mountains into villages on snowy nights. One reference relates how they bring a reviving drink of sake to anyone in need of some warmth in the snow. While there is no evidence that this alcohol-related story is actually a traditional folk tale, it certainly warms the cockles to think of this bent old hag helping out cold wanderers in the ice. Another story tells how, during times of starvation, a pale, powder-covered woman was seen washing rice at a well. No matter how much rice she removed, it would magically refill as long as there was a single grain left in the bucket, allowing her to feed all the monks of the temple.

There are many more tales to be told of winter goddesses, and wintry women of the ice and snow. In Greek myth, Chione – daughter of Boreas the God of the North Wind – is the goddess of snow. The Cailleach Bhéarra is a wise old Scottish and Irish hag who some see as a creator deity associated with winter and wilderness with many mountains taking her name, while others view her as the personification of winter or a tutelary spirit. She was embellished in the 20th century by Donald Alexander Mackenzie as ‘Beira Queen of Winter’ in Scotland, a giantess with blue skin and white hair. It said that she collects her firewood at the start of February on St Brigid’s Day (Lá Fhéile Bríde) in order to keep her warm if she plans on making winter last much longer; she will ensure fair weather on this day for her wood-gathering – a weather prediction we should all test out this coming year! In Slavic traditions, Marzanna is a goddess who dies at the end of winter, and symbolises the death and rebirth of nature in seasonal rites. There is Yuki-onna, the Japanese ‘Snow Woman’, a ghost or vampire who drifts across the snow during snowstorms as a beautiful woman without feet, sucking out the life-essence from anyone she meets, especially children. In an entirely different kind of Japanese tale, Tsurara-onna, the ‘Icicle Woman’, appears after a lonely man has stared wistfully at an icicle, wishing for a partner of his own who could rival its beauty. These tales always end with either the wife melting, or leaving at the beginning of spring, only to return and find she has been replaced, and avenging her husband’s infidelity by stabbing him with a shard of ice. An Aztec legend of two lovers mirrors that of Romeo and Juliet: Iztaccíhuatl is falsely told that her love, Popocatépetl, has been killed in war, at which she dies in grief. On his return, the man finds his love’s body and, kneeling down next to it, the gods change them into mountains and cover them with snow. This is why the mountains appear side by side to this day.

Yet these stories, dear reader, will have to wait until next year, when the snow and ice return to cover the green earth, and St Helena, the ‘hailstone saint’, walks the Balkan mountains once more, carrying icicles in her skirts…

Maypoles, Mandrakes and Mistletoe: A Treasury of British Folklore by Dee Dee Chainey

Don’t forget, Maypoles, Mandrakes and Mistletoe: A Treasury of British Folklore, is now available from National Trust Books!

‘An entertaining and engrossing collection of British customs, superstitions and legends from past and present.

Did you know, in Cumbria it was believed a person lying on a pillow stuffed with pigeon s feathers could not die? Or that green is an unlucky colour for wedding dresses? In Scotland it was thought you could ward off fairies by hanging your trousers from the foot of the bed, and in Gloucestershire you could cure warts by cutting notches in the bark of an ash tree. You’ve heard about King Arthur and St George, but how about the Green Man, a vegetative deity who is seen to symbolise death and rebirth? Or Black Shuck, the giant ghostly dog who was reputed to roam East Anglia?In this beautifully illustrated book, Dee Dee Chainey tells tales of mountains and rivers, pixies and fairy folk, and witches and alchemy. She explores how British culture has been shaped by the tales passed between generations, and by the land that we live on.

As well as looking at the history of this subject, this book lists the places you can go to see folklore alive and well today. The Whittlesea Straw Bear Festival in Cambridgeshire or the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance in Staffordshire for example, or wassailing cider orchards in Somerset.’

When I was born, some relatives told my mom to avoid cutting my nails in the first months. She didn't care and cut them. That sealed my destiny forever. According to @DeeDeeChainey's book… *check image*

Video recommending the book: https://t.co/1lTy2wBtIX#FolkloreThursday pic.twitter.com/saUyJwPbAU

— DanFF 💎 (@DanFF) January 17, 2019

‘Dee Dee Chainey… reveals a hidden Britain full of sprites and sea witches, and wild men and water horses, in this endlessly entertaining and enlightening collection of British customs, traditions and folklore, past and present.’

M.W., The Countryman Magazine

‘I think it’s easy to forget how routed Britain in mythology, legend and folklore, Greek, Norse, and countless others surround us in literature and media. But it is Chainey’s ability to write poetically, to highlight the magic in the everyday woodland or river, that makes this book so interesting. Not only is the writing style beautiful, but it is also engrossing and aims to make you extraordinarily look at the ordinary. It is easy to see how Chainey helped build up the successful online magazine #FolkloreThursday, as her writing style is so unique and entrancing.’

Ruth-Anne Walbank, SCAN, the official newspaper of Lancaster University.

‘Reading @DeeDeeChainey badass new book ‘Treasury of British Folklore’. Love how dark this book can get! Lots of ghosts too. Highly recommended!’

Shanon Sinn, author of The Haunting of Vancouver Island

‘Obviously this book cannot cover all the folklore of these jewelled isles, but it is a treasury of interesting facts about the many byways of our culture, and a guide to many customs that are still followed even today. If you enjoy learning about what makes us who we are, then this is an excellent guide.’

David Gordon

The book can be purchased here, and is now available to send to a friend as a Kindle eBook!

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References and Further Reading

Afanasyev, A., 1868, The Poetic Outlook on Nature by the Slavs, vol 2. [Accessed 30/11/2018]

Andersen, H. C., 1844, ‘The Snow Queen’, New Fairy Tales. [Accessed 30/11/2018]

Chainey, D., 2017, Gunnhild, Mother of Kings: A Viking Witch Queen Slandered by the Sagas. [Accessed 30/11/2018]

Davisson, Z., 2013, Oshiroi Baba – The Face Powder Hag. [Accessed 01/12/2018]

Grim, J. & W., 1812, ‘Mother Holle’, Household Tales, (trans. Margaret Hunt). [Accessed 30/11/2018]

Grimm, J., 1882, Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology, (trans. James Stallybrass).

Lang, A., 1897, ‘Snowflake’, The Pink Fairy Book, London: Longmans, Green, and Company, pp. 143-47.

Meyer, M., 2017, A-Yokai-A-Day: Oshiroi Baba. [Accessed 01/12/2018]

Motz, L.,1984, ‘The Winter Goddess: Percht, Holda and Related Figures’, Folklore 95. [Accessed 30/11/2018]

Naaké, J. T., 1874, Slavonik Fairy Tales, H.S. King & Company.

[Accessed 30/11/2018]

Nikolaevich Afanasyev, Alexander, 1916, Russian Folk-Tales, (trans. Leonard A. Magnus), London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. [Accessed 20/11/18]

O’ Crualaoich, G., 2006, The Book of the Cailleach, Cork University Press.

Ada M. Skinner (Ed.), 1915, Little Folks’ Christmas Stories and Plays, New York: Rand McNally & Co. [Accessed 20/11/18]

Smith, John B. ‘Perchta the Belly-Slitter and Her Kin: A View of Some Traditional Threatening Figures, Threats and Punishments.’ Folklore 115.2 (2004): 167-86. [Accessed 30/11/2018]

Walker, B., 1988, The Crone: Woman of Age, Wisdom, and Power, Harper & Row.