‘Comfort women’ statue missing in the Philippines as Japan’s wartime legacy under focus

- The monument was dismantled by Rodrigo Duterte’s government before a 2018 ADB summit to avoid antagonising Japan, and later ‘stolen’ from the sculptor

- Despite Harvard professor Mark Ramseyer arguing they were paid prostitutes, archives show Japan’s military establishment forced Filipino women to become sex slaves

President Rodrigo Duterte said the next day that while the monument was “freedom of expression … it is not the policy of government to antagonise other nations” and it should therefore be placed elsewhere.

“It was removed from Roxas Boulevard [beside Manila Bay] by pressure from Japan, directly to Duterte,” said Teresita Ang-See, co-founding director of Kaisa, an ethnic Chinese NGO which led the memorial project.

Harvard professor under fire for ‘negating’ Korean ‘comfort women’

The statue depicting a blindfolded woman wearing a traditional gown was returned to its sculptor Jonas Roces for repair and storage while the project funders looked for another location. But once they had found and landscaped the new setting, the artist “ghosted” the NGO.

“When he was finally traced, he said it was stolen from his studio,” Ang-See told This Week in Asia. But he could not produce any police report “and it weighs a tonne, it can’t just be stolen”.

Roces could not be reached for comment.

Lawyer Dennis Gorecho said Roces claimed the statue, valued at 1.2 million pesos (US$25,000), “was spirited away by unidentified men from his studio”.

After the monument was removed, a Philippine lawmaker received an unverified tip that then ADB president Takehiko Nakao had categorically told Duterte that dismantling the statue was “a condition for a loan for the construction of a subway” in Manila.

On Friday, ADB director for media and external relations David Kruger said this was “incorrect”.

“No one in ADB has ever made such a statement. We did not and do not place such a condition on any loan project in the Philippines. All project loan documents are publicly disclosed for transparency.”

Kruger added that the bank was “not involved in any loan negotiation for a subway project in Manila in 2018”. Last week the first 700-tonne tunnel boring machine for the subway project arrived in Manila, three years after the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), not the ADB, agreed to lend 104.5 billion yen (US$1 billion) for its construction.

OPPOSITION

However, the Japanese government has publicly voiced its opposition to any kind of memorial depicting the military abuse of Filipino women.

On January 9, 2018 – a month after the statue was unveiled in Manila – the government under former prime minister Shinzo Abe sent a high-level delegation led by his internal affairs and communications minister Seiko Noda to Manila to pay Duterte a “courtesy call”, according to Kyodo News.

Statue honouring wartime sex slaves removed in Philippines

Noda later told Japanese media that she had “frankly” told Duterte it was “regrettable for this kind of statue to suddenly appear” and that he understood Tokyo’s concerns.

Duterte’s foreign secretary at the time, Alan Peter Cayetano, also warned about the effect the statue could have, saying “you can’t strengthen your relationship long term if you keep bringing up things that you think are settled”.

Tokyo is Manila’s largest source of official development assistance, making up 39 per cent of all ODA, or US$8.5 billion loans and grants, in 2019. The Japanese-led ADB contributed another US$5.7 billion or 26 per cent of the total.

Rounded up in their communities against their will, kept as sex slaves, they were not paid

Tokyo was not done protesting, however. In January 2019, a second smaller bronze statue dedicated to wartime sex slaves – showing a young woman seated with hands resting on her lap – was removed by a mayor in Laguna province southeast of Manila two days after it was unveiled, even though it was inside church property.

This came after the Japanese embassy in Manila issued a statement saying, “We believe that the establishment of a ‘comfort woman’ statue in other countries, including this case, is extremely disappointing, not compatible with the Japanese government”, according to The Daily Manila Shimbun.

Coincidentally, Laguna hosts an 11-hectare memorial park built by Japan for its war dead. In 2016, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko went there to offer flowers.

South Korea orders Japan to pay damages to group of ‘comfort women’

Kaisa and other groups like Lila Pilipina and Flowers4Lolas demanded to know why the government has questioned statues that “memorialise the sufferings and sacrifices of our Filipino mothers and yet allow the presence of shrines that commemorate soldiers who killed our compatriots”.

Notable, Ang-See said, is the Kamikaze Peace Memorial Shrine in Mabalacat, Pampanga on a former airfield where Japan’s suicide pilots took off from.

According to Filipino war historian Ricardo Jose, the shrines were allowed by then dictator Ferdinand Marcos “who wanted to build up stronger ties with Japan. It was very meaningful to them because this was the biggest battleground for the Japanese during the war. They lost so many men here”.

TOUCHY SUBJECT

Jose, who has a PhD in history from Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, told This Week in Asia that the Japanese government remains touchy over the “comfort women” issue.

“They have a victim mentality because they lost the war. To the Japanese, technically, all the war things were resolved when the (1951) Treaty of San Francisco was ratified.” This ended the US occupation of Japan in exchange for Japan’s acceptance of the verdicts of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

The military tribunal, however, did not cover sex slavery although some women did testify to being raped, he said. These testimonies, kept in the US National Archives, remain sealed.

New ‘comfort women’ memorial opens in Manila, defying Japanese pressure

Randy David, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of the Philippines, recalled there were two types of “comfort women” in the country. “Karayuki” were brought in from abroad to become “sex slaves … to satisfy the sexual needs of Japanese soldiers”. The other type “were rounded up in their communities against their will, kept as sex slaves, they were not paid”.

Philippine ‘comfort women’ demand Japanese Emperor address history of wartime sexual slavery

Jose agreed with this, adding there were enough books using archival material to show that so-called “comfort stations” had forced women to become sex slaves.

For instance, Japan’s Comfort Women, written in 2002 by history professor Yuki Tanaka of the Hiroshima Peace Institute, noted that 51 testimonies of comfort women in the Philippines found “the victims were abducted by Japanese soldiers from home, work, or while walking in the street … taken to a Japanese garrison nearby, where they were raped day after day”.

Usually, around 10 girls ranging from 10 to 17 would be for the exclusive use of a company-size unit and “would be raped by five to 10 soldiers every day. None of the victims were ever paid and some were forced to cook and wash” for them, Tanaka wrote.

DOCUMENTS

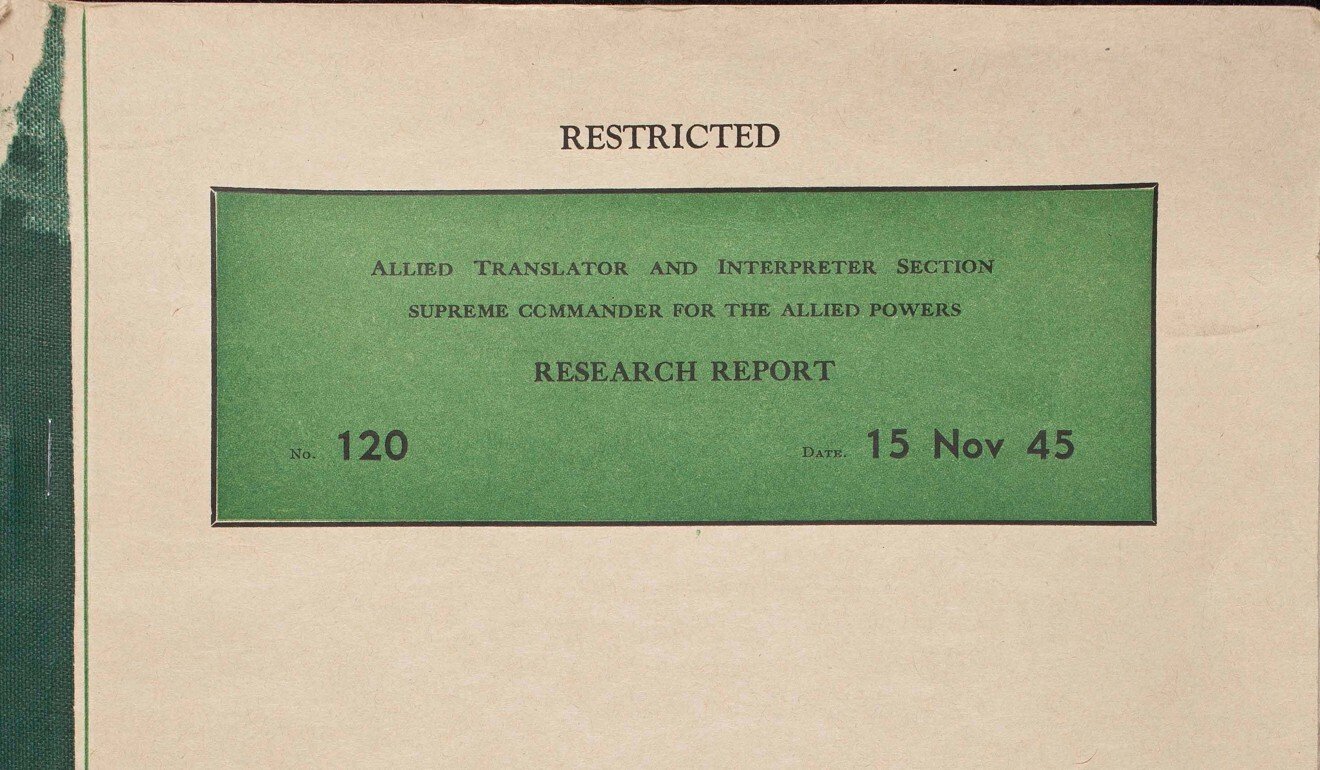

Jose said he knew the late American historian Grant Goodman who broke the story in the early 1990s about the presence of Japanese army-instituted brothels in Manila. Goodman was a translator for the US army assigned to the Philippines in 1945. The translated Japanese documents survived because Goodman had mailed a copy to his home in the US.

One of the documents translated by Goodman revealed that in Manila alone, the Japanese military kept 17 “comfort stations” staffed by 1,064 comfort women for exclusive use of soldiers, plus four officers “clubs” with over 120 women.

Another document, quoting a captured brothel owner, stated: “Every ‘comfort girl’ was employed with the following contract conditions … When a girl is able to repay the sum of money paid to her family, plus interest, she should be provided with a free return passage to Korea, and then considered free.”

In the early 1990s, the Japanese government issued a series of apologies on the “comfort women” issue after historian Yoshimi Yoshiaki found a document titled “Regarding the Recruitment of Women for Military Brothels” in the library of the Self-Defence Agency.

But this official stance was dramatically reversed in 2007 when Abe said no evidence existed that the military had kept sex slaves.

The ‘comfort women’ of South Korea: pawns in a political game?

By 2014, the Abe government “pledged to stage a campaign to correct ‘wrong’ information circulating worldwide”, according to The Japan Times.

This was despite the fact that one of Abe’s predecessors, Yasuhiro Nakasone, had written in his memoir, The Never Ending Navy, that as a young naval officer he saw that “some of the soldiers began to attack the women and gamble. So I took great efforts to build a comfort station”.

When reporters later asked him about this, Nakasone had replied according to The Japan Times: “As a Japanese person, I think it’s something Japan should apologise for … and apologise again.”