How deal for SABMiller left AB InBev with lasting hangover

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It was a deal that was meant to complete a two decade-long acquisition spree to turn Anheuser-Busch InBev into the undisputed king of beer.

Instead, the “megabrew” takeover of rival SABMiller has given its Belgian-Brazilian owner an extended hangover. AB InBev shares sit 26 per cent below the level they were at in October 2016 when the £79bn deal completed, despite a sharp rally since the start of the year. The world’s biggest brewer is still carrying $106bn in debt taken on to pay for the deal, which was intended to boost its position in Africa and Asia where SABMiller was strong.

Over the past year, AB InBev has hastened efforts to win back investor confidence by halving its dividend, replacing its chairman and promising to sell assets. The turnround arguably matters most to AB InBev’s biggest shareholders — US tobacco group Altria; Colombia’s Santo Domingo family; the three Brazilian founders of 3G Capital; and a group of Belgian families, who combined hold more than half the shares.

The latest twist in the saga came last Friday, when AB InBev recovered quickly from the failed listing of its Asian operation by unveiling the sale of its Australian business to Japan’s Asahi for $11.3bn.

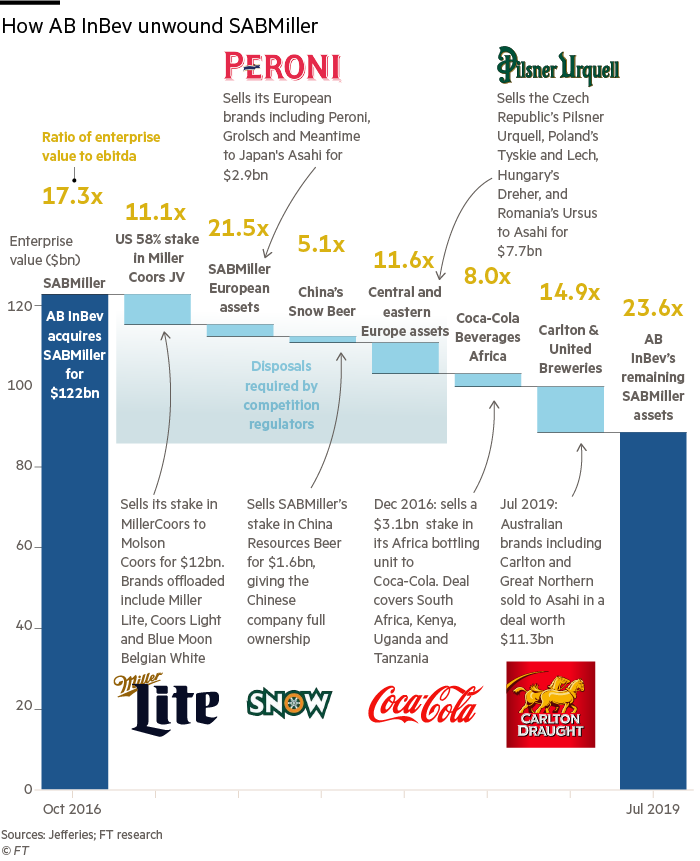

The Australia unit is only the latest chunk of what was SABMiller to go on the block. Soon after the “megabrew” deal was signed, competition authorities forced the two brewers to sell operations in the US, Europe and China to compensate for geographical overlap.

With the Australia business sold off to chip away at the debt, some industry executives and bankers are quietly questioning whether the deal for the London-listed brewer was really worth it. Adviser fees and taxes alone cost $2bn.

“Every single disposal has been done at a dilutive multiple to what they paid for SABMiller, the share price is lower, and they still have a mountain of debt to deal with,” said one top consumer industry adviser.

AB InBev disputed that critique, saying that the SABMiller takeover brought with it geographic diversification, massive cost savings, as well as a portfolio of strong brands. “Through the combination, we became a truly global brewer,” it said. “The combination had a strong strategic rationale in 2016 and it continues to have a strategic rationale today.”

Nevertheless the numbers are undisputed: to get the deal approved by regulators and then to manage debt, AB InBev has sold off parts of SABMiller worth nearly one-third of the target’s one-time enterprise value of $122.5bn. In doing so, AB InBev lost just under half of the $7.1bn in earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation that it acquired through the SABMiller, according to Jefferies analyst Ed Mundy.

The average multiple fetched by the disposals was 10.2 times ebitda, against the 17.3 times that AB InBev paid for the brewer.

On balance, Bernstein analyst Trevor Stirling still thinks AB InBev came out ahead on the acquisition because it picked up strong market positions in Africa and India, and Colombia, Ecuador and Peru where it had not had a presence before.

“We have always said the deal made strategic sense, but AB InBev paid a very high price for it,” said Mr Stirling. “Even after the asset sales, AB InBev is left with some really attractive, growing businesses with good long-term prospects.”

One bright spot from SABMiller is that AB InBev is now among the top four brewers in Africa, where the population is largely young and expected to drink more beer as economic growth gathers pace. It acquired a 20 per cent stake in the Africa business of privately held Castel, which is widely seen as a potential takeover target if the 92-year-old French billionaire owner ever wants to sell. In Colombia, it commands a near monopoly position.

AB InBev has also executed the ruthless cost-cutting for which it is known, wringing out synergies at SABMiller worth some $2.2bn annually. Much of the profit uplift from that, however, has been leached away by emerging market currencies weakening against the dollar. Since 2016, Jefferies estimates that adverse foreign exchange has cost AB InBev $2.3bn.

With the exit from Australia, emerging markets are even more important to AB InBev’s fortunes and will hold the key to whether “megabrew” lives up to its name.

Comments