I have cast my rod into the tidal current flowing around Montauk Point in New York and my lure is chugging across the surface when a bluefish swirls and fails to grab it. There is a heavier swirl. On a third appearance, the fish grabs. The hook pierces. The fish swims one way and abruptly changes direction. It darts deep. Comes up. The fish is struggling. I have never seen a free-swimming fish leap and wriggle as if to dislodge something. But this fish suddenly bursts through the surface, shaking its head energetically. It works. My lure goes flying. The line goes slack. The fish vanishes; escaped.

Was that fish feeling pain? Fear? If a sociopath is someone who disregards the pain of others, and if someone who ignores evidence is in denial, what does that make me? Such questions plague me. I cast again.

The impression that fish are insensate, short of memory and, therefore, can be caught, killed and eaten without guilt, is being revisited. Angling, the so-called “gentle art”, derives enjoyment from the struggles of its quarry. Up to 2.7tn wild fish are caught worldwide every year; a third of which are ground into feed for chickens, pigs and other fish. The ethics of all this depend on what fish do or do not experience. It is a question dividing the science community; forced to reassess in light of new evidence.

Their battle rages. In 2016, the journal Animal Sentience published Australian neuroscientist Brian Key’s essay Why Fish Do Not Feel Pain. Key had earlier written that “it doesn’t feel like anything to be a fish”. Now he argued thus: mammals feel things, and only mammal brains have a structure called the neocortex; ergo fish, lacking a neocortex, feel nothing.

But that is like saying that because we travel using legs, then fish, who have no legs, cannot travel. Key’s essay triggered more than three dozen opposing scientific responses, pressing new evidence that fish are aware; of pain, of anxiety, of pleasures.

Mine was first among the responses. I have devoted my career to conservation and to fish as wild animals. When I was a child on Long Island, I would hear toadfish croaking through the thin hull of my aluminum rowboat. Sea-robins have often grunted when I have caught one. To human sensibilities, their grunts do not sound like growling, or screaming – but what if they are just that? Even when we hear them, we don’t hear them. When you are a fish, no one can hear you scream.

Fish have honed their skills for hundreds of millions of years; humans are just making their acquaintance. Research has shown that various fish show long-term memory, social bonding, parenting, learned traditions, tool use, and even inter-species cooperation. Compared to those, pain and fear are primitive and basic.

Although aquatic farms in a handful of countries, including the UK and Norway, must follow humane slaughter guidelines, there are no standards for considering the tens of thousands of wild fish caught every second. In an essay titled Fish Intelligence, Sentience and Ethics, the Australian researcher Culum Brown suggests that the sheer scale of the global fishing industry makes the idea of legislating for the humane treatment of fish “too daunting to consider”.

But I do not have that excuse. Trying to catch just one wild fish, I have time to consider all the implications.

Asking whether fish suffer means asking whether fish possess the ability to feel at all. Brains offer only circumstantial evidence. Even behaviour can mislead. Yes, my fish jerked from the hook’s jab, but that could be merely reflexive. Yet by examining fish brains and behaviours, then comparing them to a species universally acknowledged to feel pain and pleasure – humans – we can look for clues.

Fish were ancestors to all other vertebrates; their brains were the template for our own brains’ evolution. Lynne Sneddon, director of bioveterinary science at Liverpool University, was the first scientist to discover that fish possess nerves known to convey pain. In 2002, she identified in fish the same nerve types that, in humans, detect painful stimuli. We call such nerves “pain receptors”. Sneddon showed that pinching and pricking fish activates these nerve fibres. “My research has shown that fish have a strikingly similar neuronal system to mammals,” she told me, adding that until 2002, “it was generally believed fish did not have feelings”. Nerves are not proof that fish experience pain – but Sneddon showed that fish have the necessary hardware.

The software to match this comes in the form of brain chemicals called neurotransmitters. Mammals and fish share many identical neurotransmitters including dopamine and serotonin. In humans these are involved in pain, hunger, thirst and fear, and include opiate-like chemicals that reduce pain.

Putting the hardware and software together and watching behaviour in experiments creates strong evidence. When Sneddon’s team gave trout an injection of acetic acid or bee venom – both of which cause pain in humans – the fish began breathing faster and rubbed the injection site on gravel. “Stimuli that would cause pain to us also affect fish,” said Sneddon. “When humans are in pain, we do other tasks less well. Fish consumed by pain do not respond to fear-causing situations and do not show normal anti-predator behaviour.” Yet when Sneddon’s team administered drugs such as aspirin, lidocaine and morphine, the drugs made the pain symptoms disappear. “If fish did not experience pain,” Sneddon pointed out, “then analgesic drugs would have no effect.”

In other experiments, zebrafish injected with pain-inducers swam to a normally avoided barren, brightly lit chamber of their tank if a painkiller was added there. With no painkiller to swim to, the zebrafish remained in a chamber of their tank that had hiding places and low light. When I asked Jonathan Balcombe, author of What a Fish Knows, for his take on their behavioural choices, he said: “This shows that fish will incur risk to get pain relief.”

‘How could they not feel?” fumed famed oceanographer Sylvia Earle indignantly when we spoke. “Fish have had a few hundred million years to figure things out. We’re newcomers. I find it astonishing that many people seem shocked at the idea that fish feel. The way I see it, some people have wondrous fish-like characteristics – they can think and feel!”

Fish sometimes recognise particular divers or keepers and approach them to be stroked. Earle calls groupers “Labrador retrievers of the sea”. Her daughter, Liz Taylor, now president of submarine maker DOER Marine, added that at San Francisco’s Steinhart Aquarium, “Ulysses the giant grouper would lay on his side and open his huge mouth to be petted – by certain people. He distinctly disliked some people and would blast them with water. One woman got soaked repeatedly and refused to even pass his pool. She swore ‘he knew’ she was coming. I always got a warm welcome, with eye contact. Such a good fish.”

Seafood sustainability expert Shelley Dearhart recalled “a huge grouper at the Bermuda Aquarium who would squirt water at anyone on the dock if they did not give his head a little rub – no food involved.” She showed me photos of herself obliging his desire for a rub. Pleasure; it implies a capacity for pain.

When we ask if they can feel what a human feels, we imply that that is the best a fish might aspire to. But as Earle said, fish “have senses we humans can only dream about. Try to imagine having taste buds all along your body. Or the ability to sense the electricity of a hiding fish. Or eyes of a deep sea shark.” Many fish see four major colours; humans only see three. Some see polarised light, some see ultraviolet. Some, such as flounders, move their eyes independently, processing two image fields. Archerfish and “four-eyed fish” see above and below water simultaneously, processing four images. Groupers and others signal with changing skin-colour patterns.

The long-held myth that a fish is a naturally unintelligent animal, with no memory, has no basis in research. Bob Wicklund, marine expert and author of Eyes in the Sea, told me he calls the Nassau grouper the “Einstein of the reef”. He has watched a grouper using its tail to wash bait to the edge of a fish trap where they could take a bite. Each bite pushed the bait back to the centre of the trap, whereupon the grouper repeatedly “swept” it back into reach.

Some fish learn by watching. Archerfish squirt water at bugs on leaves overhanging water. When naive archerfish watch fish already skilled at hitting moving targets, they more often hit their target on their first attempt, compared to those who never observed others hunt. How does one explain that unless fish can hold a mental image in their mind’s eye?

Some wrasses use rocks to bash urchins open. Such work cannot be reflexive. They must know when they have accomplished their mission.

Shelley Dearhart, who had bonded with a grouper, also worked at the South Carolina Aquarium, where “a huge, incredibly old cobia – apparently blind – would rest on the bottom of our largest tank,” she says. “At feeding time, a smaller, younger cobia would venture down and nudge the older one up to the surface to feed. They would swim in tandem until feeding time ended. Then the younger fish would take the older one back to the bottom. It happened daily. Seeing a relationship between two fish gave me an entirely new appreciation for the complexity of their world.”

Twenty metres deep off Cuba in 2017, I was amazed to watch several Nassau groupers closely attending two moray eels flowing in and out of coral crevices. They moved together, the eels actively hunting, the groupers expecting that a prey fish might flee its cover so they might grab it. The groupers certainly seemed to understand what they were doing, with the goal in mind.

More impressively, researchers in the Red Sea in 2002 and 2004 watched groupers and morays hunting cooperatively on numerous occasions. After one grouper chased a fish into a crevice, the grouper swam 15 metres to a cave, fetched a moray back to the hiding prey, then used posture to indicate the hiding fish. Such communication is so rarified that before this study only ravens, chimpanzees and humans were known to use “referential gesturing”. It indicates that a grouper knows that a moray, too, can know. That is “theory of mind”, and it is a big deal. Flexibile behaviour shows understanding, reflecting conscious awareness. Biologists at the University of Cambridge and the University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland wrote that groupers “perform at an ape-like level”. (But groupers came first, so we could say that apes perform at a grouper-like level.) Behavioural flexibility is the strongest evidence that – however their brains accomplish it – being a fish certainly feels like something.

Fish anatomy, neurochemistry and behaviour all indicate that fish experience sensations including wellbeing and pain. And fear. Wicklund, who dives regularly, told me about being in the middle of a massive herring school. “Suddenly, all the fish turned. Soon they were pelting us like hail stones.” Based on the time it took for the divers to see that a pack of large bluefish was on the attack, Wicklund estimated that the small fish “were communicating danger and panic throughout the school from as far as a mile away”.

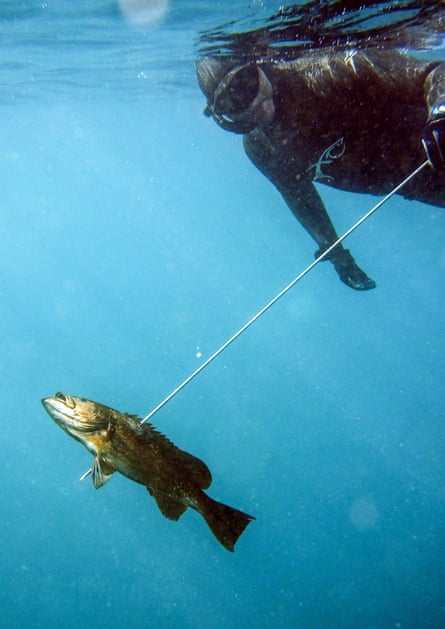

Fish act as though they remember fear. Earle recalled five cobia who were acclimated to scientific divers around an underwater lab. After spearfishermen killed three of the fish, the remaining two were – understandably – “strikingly wary”. After experimenters used a fake predator to frighten fish crossing the centre of an apparatus, fish avoided the centre. If they did cross, they sprinted, indicating a memory of feeling fear.

Undersea photographer David Doubilet, on a shoot in the Gulf of St Lawrence off Newfoundland, wanted to capture the fish’s perspective inside a herring trap. “At first the fish were swimming in slow, calm circles as I floated above them,” he said. Then the net began to rise. Tailbeats (movement in the tails) and breathing rates increased. “Chaos ensued as they lost the space between them,” Doubliet recalled. “Fish searching in vain for an exit slammed into each other.” Doubilet himself was engulfed in panic. The net tightened, concentrating the fish until, from the look in their eyes, “I could see and feel resignation set in as they stopped struggling and awaited their fate. I slipped out of the net.”

My lure and another fish have found each other. The fish tries everything it can to shake or break the connection. I work the fish alongside, and hoist it into the air. I slide the fish into an ice slurry that near-instantly chills it to stillness.

My fish has not died the way it was supposed to die. But the fish lived as it was supposed to live, by catching its own food. So if the fish could comprehend anything about me, my killing to eat might be the one thing the fish could understand.

My fish would not understand a life lived in a pen, crammed to the gills by the thousands. Most pen-raised animals – in water or air – are forced to live far worse than they are made to die.

In cold-flowing water, I have stood watching salmon returning to their birth streams from 1,000 miles away, negotiating rapids and falls, feeding bears and eagles, and people too, their life profound, nourishing and metaphorically potent.

But I once dived 20 metres into a salmon-farm pen. Their life, one slow cyclone, seemed divorced from instincts, devoid of experience. Repeatedly I was hit head-on by slow-motion salmon in a seeming stupor who made no effort to avoid bumping my face-mask or body. All senses blunted, their existence appeared robbed of meaning. It was not that their lives were over; it was as if they had never lived. Zombies.

I have been in open water hand-feeding 400kg bluefin tuna who rocketed past to snatch my handouts, yet never brushed me with a fin-tip. But I have also been on deck as one of these giants, exhausted by a long struggle with the line, was brought alongside, its eye swivelling as the gaff hook sank and its warm blood spread upon the sea. And I have watched nets that strain the sea hauled up, their strings loosened to dump the condemned on to the deck where they writhed to stillness, and only then were the desired sorted from the unwanted dead. I have seen mighty swordfish during moments of peace in warm sunlight, dozing, fin out of the water, then suddenly struck by the harpoon and shooting down, down and away while hundreds of metres of rope emptied from the baskets. A flagged buoy followed, and after dragging that rope and a length of chain for hours, the fish died 200 metres down.

Is this the relationship we want with our food? Is this the kind of people we want to be? Must we even all agree that fish suffer, when there are so many reasons to treat them better? The pain question aside, animal health specialist Ben Diggles says fish farmers “need to avoid stress at all stages to optimise health, growth and post-slaughter product quality”. He adds that “recreational angling stress can be minimised using best-practice guidelines”. But he also acknowledges that “there may be intractable issues around the inability to control injury and slaughter humanely while taking large numbers of fish in nets”.

Nerves, brain structure, brain chemistry and behaviour – all evidence indicates that, to varying degrees, fish can feel pain, fear and psychological stress. Must we insist on denying them even that paltry acknowledgment? If we do insist, let us be honest about why: it is too painful to contemplate. Fish feel pain because we refuse to.