It's been ages, if ever, since Alabama was this good in men's basketball. The program has certainly never been this entertaining or cutting-edge.

The Crimson Tide's road win against Mississippi State over the weekend clinched their first regular-season SEC title in 19 years. At 14-2 in the conference, Alabama's won its most league games since 1986-87.

Nate Oats came to Alabama in 2019 via Buffalo, where he built a mid-major behemoth in short order and made the rapid ascent from public high school coach (and math teacher) to one of the hottest mid-major coaches in a few years' time. Oats has overhauled Alabama in less than two years by deducing simple equations out of complex problems. His players and colleagues have bought in along the way, and because of that, the calculus for what Alabama's expectations should be in basketball — not within the SEC, but nationally — have shifted.

It's now March. No. 6 Alabama (19-6) is in the hunt for something it's never accomplished: a No. 1 seed (it's projected a No. 2 seed in the latest Bracketology). How it's done this so quickly is no accident, but it's also not much of a secret. Oats is disposed to disclose his methods for success; he knows it takes more than a cheat sheet and a willingness to love modern analytics in order to scale to the highest level of college basketball. Watch Alabama play and be riveted. The Tide fly. They defend like hell. They shoot fun shots while ebbing and flowing with avidity, rubber-banding back and forth to both ends of the court. At their best, Alabama's ceiling might be as high as any team not named Gonzaga.

Look deeper into why and you'll see Bama is pulling off a gambit that has rarely been duplicated. The Tide rank third nationally in adjusted defensive efficiency according to KenPom.com, yet they have the second-quickest offense in the sport (their average possession is 14 seconds on a 30-second shot clock) and that translates to an adjusted tempo of 74.5 possessions per game, which is the seventh-fastest in college basketball. Fast teams normally aren't great on defense. Alabama breaks the concept.

"I think a lot of people don't get it," Oats told CBS Sports. "Some coaches think you can't play fast and still be great on D. Well, no. You can. Offensive pace shouldn't dictate defensive effort."

Defense is winning games in real-time for Alabama, but Oats' strategy behind his offense is giving the Tide an edge before the game even tips.

Enterprising 3-point-shooting philosophy — from frequency to spacing to utilization in myriad schemes — has seen constant refurbishing in the past decade across all levels of basketball. For the past three months of the college hoops season, it's easy to argue no team at the power-conference level is treating that notion as gospel the way Alabama is. Last season, Oats' first with Bama, the Tide led all teams among the Major Seven conferences in percentage of 3-pointers attempted vs. percentage of 2-pointers attempted with 49% of its shots coming from beyond the arc. But it was barely a winning strategy on its own. Alabama finished 16-15 thanks to a suboptimal defense (114th at KenPom) amounting to a middling inaugural season.

Oats and his staff overhauled their defensive accountability in the offseason, improving from a sub-100 unit to top-three. (This is outrageous.) But they also held steadfast in their belief that the 3-point shot could be their meal ticket. A season after 3-pointers accounted for nearly half of its total attempted shots last season, Bama has turned to launching from distance again, with 47.4% of its shots from 3 powering the program's best offense in nearly two decades. Once again, it's a pace well ahead of the rest of the teams in the power conference hierarchy.

The results have been jarring. Several times this season the Tide have set program records related to 3-point shooting, including two 100-plus-point explosions against LSU and Georgia. Alabama's 115-82 win over Georgia on Feb. 13 was a program record for most points in an SEC game. Firing from afar is in itself a strategy, but Alabama has a specific deployment of shots.

The concept is not novel, though it is still fairly progressive at the college level: shoot almost exclusively either 3-pointers or at-the-rim 2-pointers. Bama bombs away from anywhere on the court when it comes to the 3-point shot, but it is avoiding mid-range shots like the plague. Alabama operates like an NBA team in a college world and has separated itself philosophically in the process. The Tide's focus is on dashing in dunks, layups, put-backs and bunnies to buttress its 3-point attack. This combines two of the most efficient shots in the sport to account for nearly 85% of the team's total shots. That tiny remaining slice of pie is reserved for non-layups and non-3-pointers.

Also known as the shots Oats detests.

"Modern basketball, you're not catching a ball and putting it on your hip and staring at the defense for five seconds before you do anything. That's not how basketball's played anymore," Oats said. "But I'm sure dad, uncle, grandpa, professional skills trainer, you're gonna do all this mid-range, triple threat, all this old-fashioned garbage."

Alabama's win at LSU on Jan. 19 is the best example of this strategy. The Tide won 105-75 without a single mid-range jumper. Thirty points came from drives to the rim, six from the free-throw line and the remaining 69 from making an SEC-record 23 3-pointers. The shot chart is a sight to behold and a testament to Oats' arithmetical belief system.

To be sure, plenty of teams are toying with and even implementing ever-evolving analytics concepts to diversify their respective offensive portfolios. Gonzaga and its second-ranked offense shoots a heavy dosage of 2-pointers as opposed to 3-pointers. What's resulted is one of the most lethal inside-the-arc offensive attacks in history. Gonzaga's making 64.4% of its shots inside the arc, which is on pace to set a Division I record. Elsewhere, Baylor boasts a top-five offense. It strikes a balance between 2-pointers and 3-pointers, but it's elite because it makes 42.1% of its treys. Bama, by comparison, hits 35.5% of its triples. Baylor is first in the country, Bama is 90th.

Another element to this: most teams prefer not to run with Alabama for 40 minutes. They want to tap the brakes. That in turn helps Alabama's transition D. Opponents also tend to send fewer players to the offensive glass — to help get back on defense — so that allows the Tide more second-chance, at-the-rim opportunities off missed 3-pointers.

Scan any and all national title contenders. The shot charts do not lie. No team commits to such a bold-yet-basic offensive doctrine: treat mid-range shots like poison. Alabama's adherence to it has powered the program to a runaway SEC regular-season title, and in the process given the Tide their most realistic chance at a national title in school history.

Oats' background as math teacher-cum-college coach links an unmistakable numerical belief system between the two vocations that has helped put him in command of one of the hastiest turnarounds in college sports. To understand why Alabama is now even more fun to watch on a basketball court than on a football field, you need to understand how Oats made it to this point.

Oats does not have a name for what he runs, but his system — call it Ball & Oats? — has been in place since his time at Romulus High School, on the outskirts of Detroit. He got hooked when he discovered a coach at a junior college in Fresno, California, had devised a new style of offense. The man's name is Vance Walberg. He'd eventually coach Pepperdine and then spend years in the NBA. Walberg is credited with inventing the dribble-drive motion offense. The basic concept — popularized by John Calipari during his time at Memphis — is to spread out the offense as much as possible by putting four players on the perimeter to create as much space to allow for slicing attacks to the rim. The ball handler, and each subsequent one, can create commotion by rippling the defense before, ideally, forcing an overcommit and thus allowing for an open shot from deep or an attempt near the rim that doesn't include a double-team.

Oats was in on this years before it went mainstream in the college basketball community, back when Walberg installed the scheme at Fresno City Community College. Oats, then in his 20s, reached out and asked Walberg if he had any instructional videos. Walberg didn't have any. All he had was game tape. So he sent Oats six game DVDs.

"Nobody really knew who he was yet," Oats said. "I was a junkie, so I kind of knew who he was. And I just made the calls and he sent me the DVDs, we studied them hard, kind of figured out the system enough."

When Walberg got the job at Pepperdine in 2006, Oats flew out with his then-high school assistant, Josh Baker, who would go on to work in college with Oats. Walberg spent about a week teaching the two about the dribble-drive. They returned to Michigan, where Oats would hold a 222-52 record, win seven conference championships in a row and take a state title in 2013 using similar concepts then to what has vaulted Alabama into the top 10 today.

"We had athletes, we spent a ton of time in the gym developing them," Oats said. "I didn't want them to turn into robots, so we played open, fast, free. Our entire offseason, even during the year, we're in the gym at like 6 a.m. doing all skill development. When you're going to spend that much time in the gym developing players, you don't want to run flex or, you know, Bobby Knight motion offense. You're trying to open the floor up, let your skill players have some space and freedom to play."

Oats' reputation soon grew large enough — he was coaching a public school to top-25 status nationally — that he left his Romulus classroom behind and joined Bobby Hurley's Buffalo staff in 2013. When Hurley left for Arizona State in 2015, Oats was promoted and led Buffalo to three NCAA Tournaments in four years. The pinnacle was a record-shattering 32-4 season in 2018-19 that was highlighted by a second straight season with an NCAA Tournament victory and a program-record No. 6 seed. It's what got him the Alabama gig, and he brought his philosophy with him to Tuscaloosa.

In his first week Oats brought the team in for math class. He had every player's numbers on a whiteboard and he compared their averages to the Buffalo team he just left behind that finished 22nd at KenPom with a 32-4 record. It was a team that ranked 21st in offensive efficiency, 31st in defensive efficiency and was the 11th-fastest team in college basketball. It ranked in the top three in transition defense efficiency that season as well, according to Synergy Sports. Positively an elite combination for a mid-major team to pull off.

So Oats explained how to calculate points per possession. For example, 40% on a 2-point shot equates to .80 points per possession.

"I told them what their defensive efficiency numbers were the last year, I said, 'You'd lose every game if you're getting 0.80," Oats said. "Your defense isn't going to be that good. It's impossible."

But a layup? If you can make 60% of your layups — an achievable number — the points per possession inflates to 1.2. At that rate, Oats told his new team, they'd have won around 90% of their games instead of finishing 18-16. And the 60% from 2 equates to the same as if you're 40% from 3-point range; both are 1.2 points per possession. Even 35% is a hair over 1.0.

"Anywhere between 1.0 and 1.2, you got a chance to win," Oats said. "I said, 'Here's the deal, we're not going to shoot very many mid-range shots. The only way it's going to be a good shot for you is if you're 50% or above,' and I gave them some of the best shooters in the NBA, some of the best mid-range shooters are still in the 40s. Most of them are."

Oats put a scoring system in place for practices that is as simple as it is clever in getting his ideology across. The team plays games to 8 or 12 points. You get one point for a mid-range jumper or long 2-pointer, two points for a layup or a shot very close to the rim, and three points for a 3-pointer. Oats' staff charts everything in practice. He does not believe in information overload. Activity begets data which begets analysis which begets areas to improve. Always.

"[Jahvon] Quinerly comes in, he thinks that's his shot," Oats said. "OK, so we let him shoot it still. He gets one point for them, but we don't make it where you can't shoot it. Then, after a month of data in practice, we show them: Bro, you're shooting 30%, like that's 0.6 [points per possession]. We can't win games like that. The offense isn't efficient when you're doing that, and eventually you kind of break them of their bad habits."

There's even a 4-point line (about four feet behind the NBA 3-point line) on Alabama's practice court that enables effective, expansive spacing. (It shows the players how they can materialize wide-open shots in the flow of their offense with their cadre of capable long-distance shooters.) These hyper-competitive scrimmages also have incentives in the scoring system that award bonus points for the right pass in the right spot that leads to a made shot.

Alabama’s practices include highly competitive scrimmages to 8 or 12 points. This is how Oats has broken mid-range shooting habits. The breakdown:

— Matt Norlander (@MattNorlander) March 2, 2021

1 point: mid-range/long 2

2 points: at-the-rim 2

3 points: college 3

4 points: Steph/Dame-land

Here’s what the court looks like. pic.twitter.com/SJtiVhDcBm

There's defensive penalties as well. If a team gives up an uncontested layup, even if the score in a game to 8 is 7-0, the leading team that gives up the layup loses 8-7.

"This year, nobody's going to play if they don't want to guard," Oats said. "We're not giving up transition layups, period."

Through repetition, the team will understand what is an efficient shot and what is not. Oats de-incentivizes the needless. Soon enough, the guys don't want to take those shots in practice because they don't want to lose. And then those habits transfer almost in full in games.

"Most people can understand the numbers behind it. It's not that complicated," Oats said. "But you've got to be able to have an offense that generates at the rim and open 3s. You don't want to just jack up 3s, that's bad basketball. If your offense generates a lot of mid-range 2s, but you talk about the numbers, it makes no sense. If you're going to run Bobby Knight motion, you're gonna get a lot of mid-range 2s … You've got to have an offense that generates at-the-rim 2s and kick-out 3s."

Now Alabama's in program-record territory this season the way Buffalo once was.

There's one more important edge Alabama has this season that most other teams don't: its own independent analytics department.

Every NBA team nowadays employs, at minimum, a small in-house analytics staff. Some are much deeper than others, but you can't run a franchise without that type of objective analysis informing your front office. At the college level? No. That's not happening. No university can, or chooses, to afford to employ a team of people solely dedicated to studying the trends, diving into the numbers and swimming in the data to give you an upper hand. Some schools have a person assigned to look at some data, and that can provide gains, but it's a far cry from paying people a full-time wage to track data drifts and uncover layers and layers of new-age analytics.

Enter: HD Intelligence.

It's a two-year-old company that outsources itself specifically to college programs, playing the part of full-time analytics department in the process. HD Intelligence (HDI) is owned and operated by two men in their 30s: Colton Houston and Matt Dover. The former was a director of operations at Alabama for almost a decade; coincidentally, when Avery Johnson left the program in 2019 it coincided with Houston leaving Alabama to start HDI. Dover's background comes from the political world, where he worked with analytic think tanks and was involved in Barack Obama's and Hillary Clinton's presidential campaigns.

Right around the time Oats was using a whiteboard to explain points per possession to his new team in Tuscaloosa, Houston was making the pitch to Oats about what his new company was doing and why it could make Alabama a lot better a lot quicker.

"A huge part of our value is not just providing data, there's a lot of value in that, but based on my experience at Alabama I'm convinced that the primary way that we bring value to a staff is by helping them interpret and understand the data," Houston said. "There's a lot of written communication. There's a lot of getting on the phone. There's taking calls. There's a relationship, essentially, and so I think all 10 of our clients feel like they could call us or email us to reach out, they're going to get a quick response."

Charlie Henry, one of Oats' assistants, has an NBA background. He saw huge potential with HDI. This was a clear edge. Oats didn't need much convincing. Alabama had the budget — HDI's low-five-figure price for the year was doable — and the coaches believe it's given them a distinct advantage. For Alabama, it's been a windfall this season: experienced roster, a team that buys into the math methodology, and now a third-party analytics department that has given the team a crucial advantage in the margins with statistics and trends most other opponents might not even be aware of.

"Ninety percent of these coaches are looking at KenPom, which is a great site and they should be looking at that, but we're able to go, I think, a little more in-depth with each opponent," Houston said.

HDI provides immersive, eye-catching statistical scouting reports for opponents with next-level data, charts and a lot of written analysis as well.

"Scouting-wise it helps us point out inefficient areas, offense and defense both," Oats said. "They send us leverages in lineup analysis, like when you've got these two players on the floor together you're not good at this, stuff like that. They point out areas and deficiencies that you wouldn't really think of on your own."

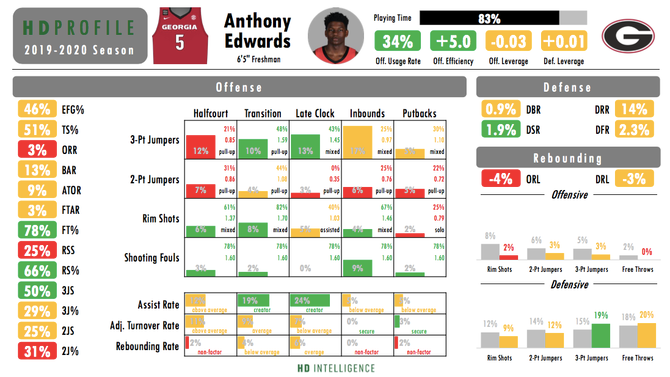

As an example, here's a sampling of the kind of analysis HDI sent to Alabama's staff last season when it was prepping to play Georgia and future No. 1 pick Anthony Edwards.

Oats has come to love the next-level data so much, he normally waits to get the initial postgame HDI box score (sent to his email within 10 minutes of the game going final) before he talks to the media after. This tactic caught Furman coach Bob Richey's attention early in the season. Alabama beat Furman on Dec. 15. After the game, Richey heard Oats referencing a few weird stats and didn't know what Oats was talking about and how he had that data from a game that finished minutes earlier.

So Oats told him about HDI. Then Furman signed up. The company is working with eight men's teams and two women's teams and plans to expand next season. HDI also provides services on optimal scheduling and looking through the transfer market as a completely separate amenity. That service has boosted Alabama even more this season.

"They help with the recruiting and especially in the transfer market, because they can pull up like (Jordan) Bruner for instance," Oats said. "They send us offense leverage, defense leverage — basically, are we better when you're in the game versus when you're out? Well, last year we were 12 points better per 100 possessions on the defensive side when Herb Jones was in the game, which makes sense, he was our best defender. Everybody knew it. But Yale was 18 points better per 100 possessions when Bruner was in the game versus when he was out. So as good as Herb was for us, Bruner was 150% better for Yale."

Oats is a night owl. He'll sometimes send texts to Houston or Dover well after midnight, a signal he's watching tape and looking over HDI's data. Oats landing the Alabama job at the same time Houston and Dover started HDI was serendipitous. Houston pointed out it's not as simple as signing up for HDI. It takes a real craving for wanting to understand all the numbers and to implement them to make it work.

"You have to have a coach and a coaching staff that is kind of on the same page and has an idea of how they want to play," Houston said. "We're taking zero credit for the fact that Alabama avoids mid-range shots. Nate was fully on that before he ever heard of us. It's more about what tools, information and kind of interpretation of the data can we provide to them, to help them do what they want to do but do it better."

With the NCAA Tournament a little more than two weeks away, Alabama's biggest basketball moment might be soon arriving. But the biggest ramification of the Ball & Oats dogma won't be how far Bama advances in the bracket. College basketball is a copycat sport that's nevertheless still slow to change. Alabama is the change. Oats has fashioned a modern model, and within a few years' time there will no doubt be a parade of programs following the path laid down in Tuscaloosa.