Only 1% of British children’s books feature a main character who is black or minority ethnic, a investigation into representations of people of colour has found, with the director calling the findings “stark and shocking”.

In a research project that is the first of its kind, and funded by Arts Council England, the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) asked UK publishers to submit books featuring BAME characters in 2017. Of the 9,115 children’s books published last year, researchers found that only 391 – 4% - featured BAME characters. Just 1% had a BAME main character, and a quarter of the books submitted only featured diversity in their background casts.

This compares to the 32.1% of schoolchildren of minority ethnic origins in England identified by the Department of Education last year.

“It is a stark and shocking figure when you see it in print,” said Farrah Serroukh, who directed the project for the CLPE and presented it to publishers on Monday.

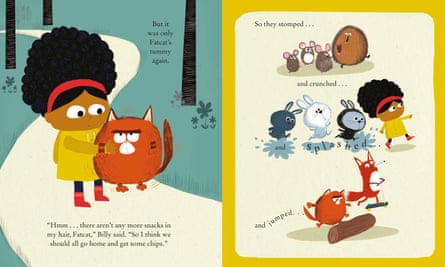

The researchers also analysed the quality of the representation, as well as the quantity of BAME characters. They found that more than half the books featuring a BAME character were classed as “contemporary realism”, and 10% contained “social justice” issues, such as war and conflict. Only one children’s book featuring a BAME character was defined as comedy.

“Do those from minority backgrounds only have a platform when their suffering is being explored? And how does such disproportionate variation of representation skew perspectives of minority groups?” asked the report.

“Topics such as conflict and the refugee experience are valid subjects for authors to explore and unpick. Our concern would be if children only encounter ethnic minority representation in that context and no other,” Serroukh told the Guardian. “We need books like that, but they need to sit within a wider diet of books so readers can appreciate that people from minority backgrounds have as much variety of life as everyone else – yes, there is struggle, but there is also going to the dentist, going to the supermarket. It’s striking a balance.”

The report states that “every child is entitled to feel safe and valued”, and that “in the current socio-political and economic climate the risk of marginalisation is even greater”. It warns publishers that if children do not see their realities reflected in the world around them or only see problematic representations mirrored back at them, the impact can be tremendously damaging.

“To redress imbalances in representation is not an act of charity but an act of necessity that benefits and enriches all of our realities,” the report adds.

Author Nikesh Shukla, who has been a major force behind the push for diversity in UK publishing, sat on a steering committee for CLPE’s report.

“I do feel the industry is getting better but a report like this is a reminder of how much work still needs to be done – and a stark reminder of our readers, and how our readers are not getting what they need,” he said.

“When you’re figuring out the world, being able to see yourself in books, as well as people who don’t look like you, is really important. It means you see your story as valid, and it can contribute to who you imagine yourself to be – and a kid should be able to imagine themselves as anyone in the world. These mirrors are so important.”

His words echo those of the late American children’s author Walter Dean Myers, who wrote in 2014: “Books transmit values. They explore our common humanity. What is the message when some children are not represented in those books? … Where are black children going to get a sense of who they are and what they can be?”

Serroukh said that the CLPE had plans to work with publishers to help them improve. Recommendations include increasing investment in authors from a range of backgrounds, looking for stories where main characters are BAME, and ensuring that they are not “predominantly defined by their struggle, suffering or ‘otherness’”.

“At the moment, every title out there featuring BAME characters shoulders a heavy weight. It has to fulfil so many expectations,” said Serroukh. “It comes back to the issue around volume. If there are more books which are representative, then there is more opportunity for wider experiences to be expressed.”

Serroukh writes in the report’s foreword: “We know that those who work in all areas of children’s books and literacy recognise that there is work to be done. We want to channel the momentum to ensure that this isn’t reduced to an awkward footnote or ‘trend’ in the history of UK children’s publishing because something as integral as a person’s identity and sense of self deserves to be recognised, respected and valued now and always.”

Like a long-running equivalent survey in the US from the University of Wisconsin-Madison – which has charted a slow increase in BAME characters over the last decade and a half – the CLPE report is intended to be annual. A separate piece of research, by the BookTrust, is also currently under way, examining the number of authors and illustrators of colour working in children’s publishing. The BookTrust findings are due in September.

Serroukh said she hoped CLPE’s research would be useful as a starting point to help publishers reflect. “Hopefully in 10 years’ time, or however long, it will become redundant,” she said. “We are really keen for the UK market to develop a more nuanced conversation. We don’t want to be talking about volume in three years’ time, but about quality.”