Understanding the ‘rise’ of the radical left in Europe: it’s not just the economy, stupid

A considerable amount of attention has been paid to understanding the electoral rise of populist radical right parties in Europe. However, much less research has focused on understanding the recent electoral fortunes of the populist radical left across Europe. James F. Downes, Edward Chan, Venisa Wai and Andrew Lam argue that three key factors, in the form of the 2008–13 economic crisis, the decline of the centre left and Euroscepticism can partly explain the post-crisis electoral growth of populist radical left parties in Europe. In addition, it is important to note that this electoral growth is higher than centre left and right parties, but considerably lower than populist radical right parties.

Picture: Thierry Ehrmann, via a (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) licence

Picture: Thierry Ehrmann, via a (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) licence

Defining the radical left

The radical left party family is diverse and there are a number of different definitions in the literature. Recently, some scholars have suggested that there is a general consensus in the core features that make up the radical left. In summary, these are:

- Far-left parties encompass two main subtypes; ‘radical’ left and ‘extreme’ left. They are not merely on the ‘left’ of social democracy and are clearly distinct. Notably, while the radical left tends to support forms of direct democracy, the extreme left denounces liberal democracy.

- Scholars such as March and Mudde argue that the radical left is ‘left’ in its identification of economic inequality as the basis of existing political and social arrangements, and its positioning of economic and social rights as its core agenda.

- It is ‘radical’ in that it proposes deep-rooted change to the socio-economic structure of contemporary capitalism that involves redistribution of resources from existing political elites.

- It is internationalist in terms of its focus on cross-national networking and solidarity, and in its aim to put themselves in the vanguard of opposition to globalisation, neo-liberalism and imperialism.

Electoral success

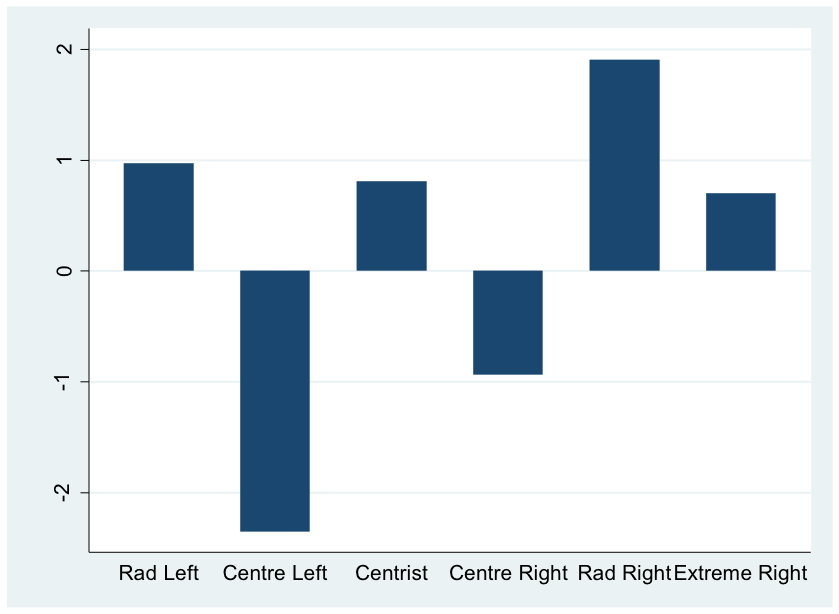

Figure 1 depicts the overall percentage change in vote share for different types of political parties in the last two national parliamentary (legislative) elections that cover roughly the electoral periods between 2011 and 2018 in 28 EU member states, and which coincide with the ongoing refugee crisis. Figure 1 demonstrates that radical left parties increased their overall vote share by around 1% point and is higher than both centre left and centre right parties. However, this figure is fairly small when compared with the rise of radical right parties. Figure 1 also depicts a bleak picture for centre-left parties, who saw their overall vote share decrease by more than 2% points. Recent cases such as the ‘rise’ of Podemos in Spain (2014), Syriza in Greece (2015), Left Bloc in Portugal (2015), Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France (2017) and the shift of the UK Labour Party (2015) under Jeremy Corbyn further demonstrate these patterns. The Catalonia crisis that began in October 2017 also indicated the significant power that radical left politicians can wield. It is important to note that electoral success for the radical left is not uniform, with some parties faring less well electorally.

Figure 1: Percentage vote share change for different types of political party (last two national parliamentary elections amongst the EU28)

Source: Author’s own dataset; notes: N= 224 parties

Figure 2 below demonstrates these uneven patterns further. For example, Podemos formed a leftist alliance with the former Communist Party (United Left) in June 2016, yet they failed to build on their momentum which earned them 21% of the total vote share in 2015. The newly formed alliance could not overtake the Socialist Party as the largest party among the left in Spain. Syriza suffered a hiccup in the snap election in September 2015, when their vote share declined, arguably as a result of accepting a new EU bail-out package. Nonetheless, they were still able to remain the incumbent party.

Figure 2: Percentage vote share and seat share change for selected radical left parties (last two national parliamentary elections) in the post-crisis period

| Country (election years) | Radical left party | % Change in vote share for radical left parties (+/-) | Overall change in seat share (+/-) |

Electoral success? |

| Finland (2011/2015) | Left Alliance (VAS) | -1 | -2 | No |

| Germany (2013/ 2017) |

Die Linke (The Left) | +0.6 | +5 | Yes |

| Greece (Jan 2015/ Sep 2015) |

Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza) | -0.8 | -4 | No |

| The Netherlands (2012/2017) | Party for the Animals (PvdD) | +1.2 | +3 | Yes |

| Portugal (2011/2015) | Left Bloc (BE) | +5 | +11 | Yes |

| Portugal (2011/2015) | Unitary Democratic Coalition (CDU) | +0.4 | +1 | Yes |

| Spain (2015/2016) | Unidos Podemos (Podemos-IU) | -3.3 | 0 | No |

Notes: Electoral success means that a radical left party increased their vote share in the most recent national parliamentary election. A selection of recent elections is presented for the sake of parsimony.

The 2008–13 economic crisis: ‘Pasokification’

The economic crisis hit incumbent parties hard, particularly those on the centre left. A number of European countries such as Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain spiralled into economic recession following the eurocrisis. It is important to note that countries within the eurozone do not have an independent monetary tool and austerity largely became the only solution available for domestic governments. While there are parties calling for a revamped EU democracy that retains complete monetary sovereignty, the austerity policies remain a seedbed for the radical anti-establishment to mobilise public frustration towards incumbent governments and the EU. This has been the strategy for success among radical left parties such as Syriza and Podemos.

Euroscepticism: the cases of Syriza and Podemos

While the mainstream media and the broader European community depicted austerity as the only way out, the disenchanted masses were disappointed about their lack of real choices. Syriza mobilised such sentiments and gained their popularity in the form of a grassroots movement and their vote share skyrocketed from 4% in 2014 to 36% in 2015. Eurosceptism has been at the heart of the Podemos political platform as they confronted the prevailing austerity policies in the European establishment. The radical left reaped their fruits during the post-crisis period. They accounted for 9% of the vote share in their respective national elections during 2008–2014. There was an increase in vote share by 2%. In particular, the collapse of the centre left PASOK allowed Syriza to gain significant electoral space from PASOK. In addition, Die Linke in Germany maintained a sizeable influence in the Bundestag with 69 seats despite the daunting challenge from AfD in eastern Germany at the 2017 federal election. Thus, the radical left has achieved a high degree of electoral success in the post-crisis period.

In a recent paper, the authors argue that nationalism is the common denominator of both radical left and radical right Eurosceptism. The radical left equate nation with class as they are against class exploitation. Civic nationalism is embraced. For the radical left, the EU is often portrayed as a sign of imperialism as they seek emancipation and independence from great powers. However, tensions remain for radical left parties on the issue of nationalism and internationalism, which need reconciling.

Radical left parties’ rejection of the EU stems from the EU’s tendency towards a neoliberal market structure, but not an opposition to European integration. Both Syriza and Podemos espouse a positive integration model based on social and inclusive policies alongside democratic institutions. They do not offer a binary choice between austerity as an EU member and anti-austerity as a non-EU member. They have focused on austerity as an issue while confronting the undemocratic and neoliberal EU political order. Despite being labelled as Eurosceptic, the radical left’s strategy on Eurosceptism is ‘softer’ than the radical right and not in opposition to European integration outright.

Implications for liberal democracy

Recent research has demonstrated that radical left parties are increasingly becoming part of the mainstream in European politics. The electoral rise of insurgent radical left parties in recent years demonstrates two key patterns, namely: the ever-changing European political landscape and widespread patterns of electoral volatility. Recent landmark events such as the eurozone crisis have coincided with the significant decline of centre-left parties. This has enabled a number of radical left parties to perform well electorally in the post-crisis period, in offering credible alternatives on key issues such as nationalism and EU integration that have resonated well with voters.

As we have argued in a recent article for LSE’s European Politics and Policy blog, the electoral decline of traditional centre-left parties should not be taken lightly. Voters have become disenchanted with the policies held by a number of centre-left parties on issues relating to the handling of the eurozone crisis and further EU reforms. A number of radical left parties have clearly cut across these issue domains and appealed to disgruntled voters, who have sought more radical alternatives over mainstream parties. Nonetheless, the electoral gains for radical left parties are considerably lower than those observed for radical right parties in the post-crisis period. This is an important area for future research to explore.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

This article is part of a wider project that examines ‘The Electoral Decline of Social Democratic Parties in Europe’ and involves the creation of an original aggregate level dataset that covers the post-economic crisis. The project details can be found here.

About the authors

James F. Downes (Twitter @JamesFDownes) is a Lecturer in Comparative Politics in the Department of Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is also an Affiliated Visiting Research Fellow (Honorary) at the Europe Asia Policy Centre for Comparative Research. He is also a Data Advisor for the Local Democracy Dashboard project, based at the London School of Economics.

Edward Chan is a Government and Law double degree student at the University of Hong Kong.

Venisa Wai is a Government and Law double degree student at the University of Hong Kong.

Andrew Lam is an MPhil student in Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Radical left parties performed well electorally, but their electoral gains were considerably lower than those of radical right […]