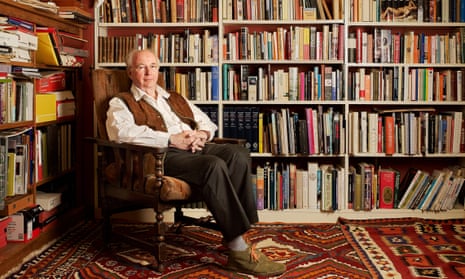

Philip Pullman, Antony Beevor and Sally Gardner are calling on publishers to increase payments to authors, after a survey of more than 5,500 professional writers revealed a dramatic fall in the number able to make a living from their work.

The latest report by the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS), due to be published on Thursday, shows median earnings for professional writers have plummeted by 42% since 2005 to under £10,500 a year, well below the minimum annual income of £17,900 recommended by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Women fare worse, according to the survey, earning 75% of what their male counterparts do, a 3% drop since 2013 when the last ALCS survey was conducted.

Based on a standard 35-hour week, the average full-time writer earns only £5.73 per hour, £2 less than the UK minimum wage for those over 25. As a result, the number of professional writers whose income comes solely from writing has plummeted to just 13%, down from 40% in 2005.

The median income of the writers surveyed – including part-time and occasional authors – has declined in real terms to £3,000 a year, down 33% since the last survey in 2013, and 49% since the first ALCS report in 2005. Professional writers are defined as those who dedicate more than half their working hours to writing.

Pullman, Beevor and Gardner claim the crash in number of professional writers is threatening the diversity and quality of literary culture in the UK. They lay the blame at the door of publishers and online booksellers, which over the same period have failed to share a greater slice of their rocketing profits. In 2016, UK publishers’ sales of books and journals rose 7% to £4.8bn, a trend repeated in 2017 as UK books sales alone passed the £2bn mark. Since 2005, Amazon’s global turnover has risen from $8.49bn (£6.4bn) to $177.87bn.

“The word exploitation comes to mind,” said Pullman, bestselling author of the His Dark Materials series and president of the Society of Authors. “Many of us are being treated badly because some of those who bring our books to the public are acting without conscience and with no thought for the future of the ecology of the trade as a whole ... This matters because the intellectual, emotional and artistic health of the nation matters, and those who write contribute to the task of sustaining it.”

Amanda Craig, whose latest book, The Lie of the Land, was published in 2017, said: “Women invariably do the majority of childrearing, which can mean they have 15 years or more of lower earning, particularly in something like fiction, which demands such a lot of concentration,” she said.

Beevor, author of breakout bestseller Stalingrad, echoes Pullman’s concerns, adding that non-fiction authors face a particular problem if they have little money to fund their research. “Stalingrad took four years’ work, which was funded by publishing deals from the UK and abroad,” Beevor said. “I had tried writing part-time in the evening, but you are too knackered at the end of the day and I couldn’t do it.”

He added that the decline in earnings threatened the diversity among writers and would favour economic advantage over talent. “We need professional writers, because otherwise only those with other sources of income will be able to write.”

Nicola Solomon, chief executive of the Society of Authors, criticises publishers and Amazon for not sharing a greater percentage of their booming profits with the people who supply their raw material. “What concerns us is that during the same period that we see authors’ earnings plummet, the large publishers are seeing their sales rocket,” she said.

Solomon estimates that payment of authors accounted for a mere 3% of publishers’ turnover in 2016. “The industry pays so little for the raw material. Publishers talk about diversity then pay lip service to sustaining writers’ careers. They have a responsibility to see that authors are properly paid and their earnings do not go down,” she added.

“When I started you could still make an okay living from writing. You can’t do that now,” said Sally Gardner, whose bestselling novel Maggot Moon won the Carnegie medal and Costa children’s book award, but came 20 years after her first book.

As a result, she said, the ability of authors to craft their ideas over years and write books that tackled important questions had been seriously undermined. “Now the publishing business wants bestselling novels at whatever cost, but to develop talent and great writing you need patience, encouragement and financial support,” she added.

Publishers being risk-averse had led to a situation where celebrity authors were leaving others with a smaller pool of money to compete for, Gardner added. As a result, authors were finding it harder to get novels that asked big questions into print.

Tony Bradman, children’s writer and chair of the ALCS, said there would be long-term consequences to the underfunding of writers. “It is shortsighted in business terms to say it doesn’t matter [if we have few professional writers], just throw money at the big names and it will work,” the Dilly the Dinosaur creator said. “If they don’t work, where are the authors to replace them?”

The 2018 ALCS survey covers writers from fields including stage and screen, but authors appear to fare worse than their counterparts in the creative arts. “If I had to rely on being a novelist, I would be skint,” said Jonathan Harvey, a novelist who supports his books with a day job as a playwright – his latest is the Dusty Springfield musical called Dusty – and as head scriptwriter for Coronation Street.

“It wasn’t until my 11th book that I started to get royalties,” he said. “How many people can afford to go that long without money from another source?” In contrast, he continues to earn 8%-10% of box office receipts from new productions of his debut play, Beautiful Thing, which opened in 1993.

“Authors are not a special case, deserving of more sympathy than many other groups,” said Pullman. “We are a particular case of a general degradation of the quality of life, and we are not going to stop pointing it out, because we speak for many other groups as well.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion