Then & Now | Liu Yichang’s death marks end of an era for Chinese literature

For Shanghai-born Liu and fellow writers of his generation, Hong Kong became a refuge from the political turmoils of China post-1949, yet retained a connection to home

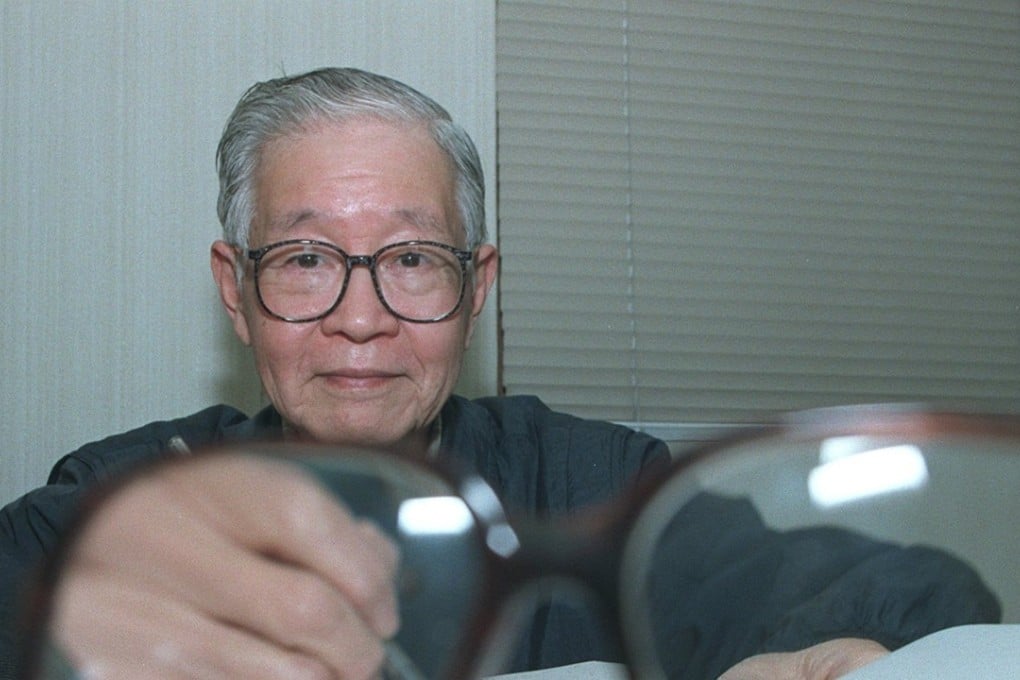

The death this month of Liu Yichang, better known to the Cantonese-speaking world as Lau Yee-cheung, at the age of 99, ends a remarkable chapter in Hong Kong’s post-war literary history.

Born in Shanghai to a scholarly family, Liu graduated from St John’s University. From his generation, the Shanghai institution produced an impressive assortment of writers and public figures; former vice-president Rong Yiren was an alumnus.

The Chinese intellectual circles of 1930s Shanghai that Liu moved in continued to echo with the dispersal of the city’s literary scene to the wartime capital Chungking (now Chongqing) in the early 40s, and overseas in the 50s. Internal and, later, foreign exile sharpened both creative and survival instincts. As China descended into civil war and a Communist assumption of power became inevitable, Liu left Shanghai for Hong Kong in 1948.

From the time he arrived in the colony, Liu recognised that money-focused, proudly philistine Hong Kong was not a place where literary talent would thrive and, from 1952 to 1957, he edited a variety of Chinese-language publications in Singapore and Malaya.

Southeast Asia in the 50s offered émigré Chinese writers such as Lin Yutang, Liu and others – as well as long-term foreign residents such as Peter Goullart and John Blofeld, whose lives and literature were deeply rooted in China – a welcoming (if small and somewhat self-referencing) cultural milieu, and a safe haven from the political turmoil of their home country.

With its brashly mercantile, expatriated-Chinese world, Southeast Asia was, ultimately, too remote from the Chinese cultural mainstream for any serious literary creativity to flourish. For their particular talent to blossom, writers such as Liu needed, somehow, to be in China, yet – during the political campaigns that periodically convulsed the Communist state – remain safely not of it. Hong Kong – neither Communist not Nationalist – offered a solution, and some surprising literary flowers bloomed during this period in the British colony’s otherwise unpromising cultural soil.