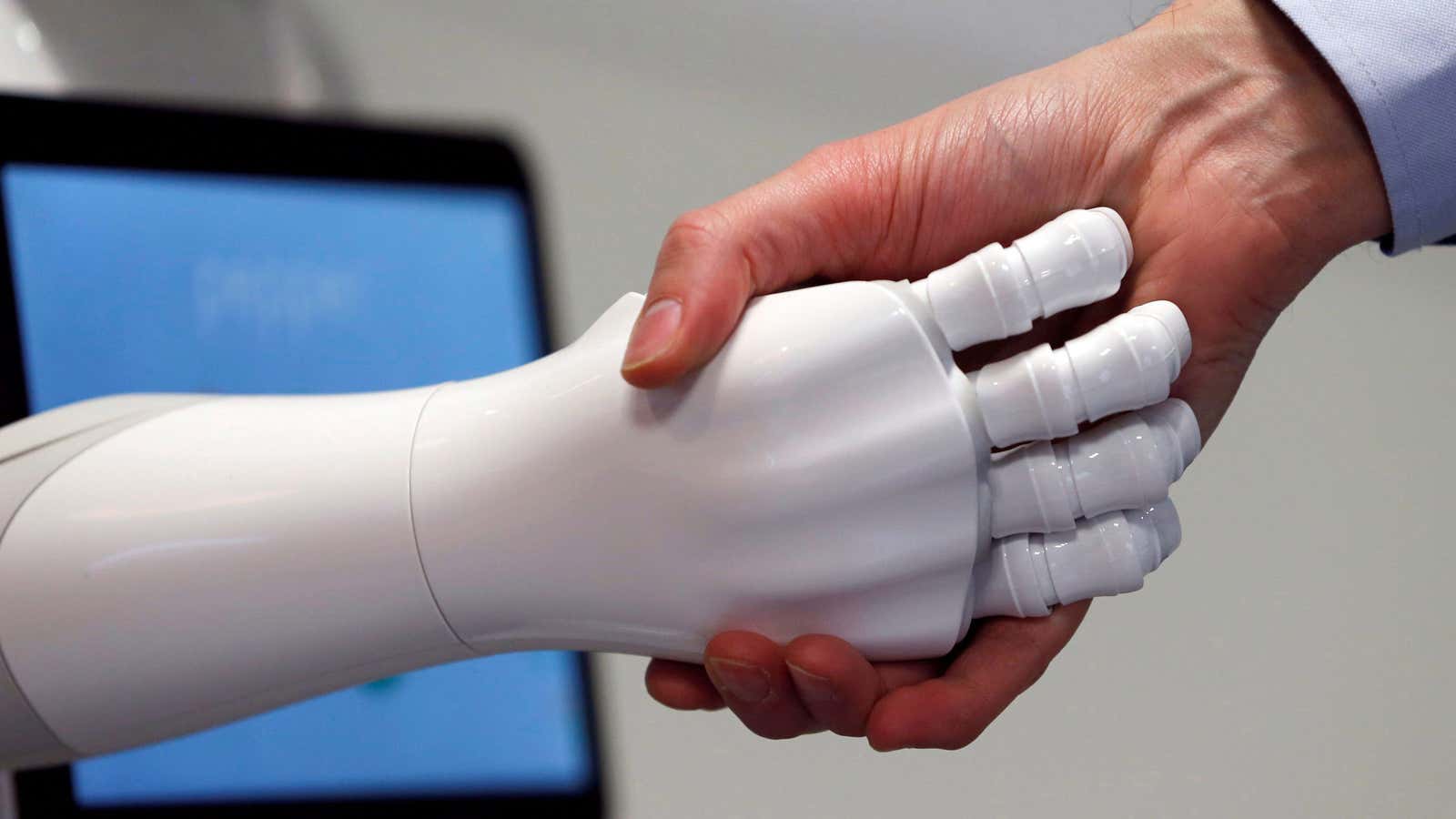

Of all the economic anxieties facing workers today, there is something particularly disquieting about the potential of automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and other technologies to replace human jobs. Self-cleaning robots, cloud-based computing, kiosks at nearly every retail store: rapid technological advances such as these have already begun to upend entire industries, with millions of more jobs in their path.

While there is significant debate among economists over the severity and speed of these changes—some studies indicate that as many as 47% of today’s jobs could be replaced by technology, while others are much more conservative in their forecasts—there is little disagreement that automation is a real and growing threat.

One would assume, given the potential size and scope of these changes, that there’d be robust discussion around how best to prepare for this coming economic transformation. There hasn’t been. Even the few policy proposals that have emerged to respond to technology-driven job displacement, such as the idea of a universal basic income, largely just cushion the harms brought by job losses.

The primary goal of policymakers grappling with the future of work should be to ensure that individuals and communities don’t just “get by” after losing a job to automation, but are equipped to lead new lives, with new jobs in new industries. A monthly stipend from the government is a good and needed start, but it only goes so far if an unemployed worker isn’t able to find a new, reliable source of income.

Fortunately, we already have a federal model that, with some modifications, can prepare us to respond to the challenges of technological unemployment: the federal Trade Adjustment Assistance program (TAA). Created in 1962 at a time when Congress was seeking to bolster public support for trade liberalization, the TAA helps groups of workers that are negatively impacted by trade stay afloat during hard times and find new paths to employment. If an individual loses his or her job primarily due to trade—say, if their company moves production overseas—they can become eligible for enhanced reemployment services.

As international trade has increased over the years—and with it, the impact on American workers—so too has the TAA evolved and expanded. Today the program has a two-pronged approach: first, it lessens the hardships faced by displaced workers (through benefits like extended income support, wage insurance, and maintaining of employer-based health insurance); and second, it redeploys human capital (through support for a wide variety of retraining programs, including post-secondary education, classroom training, and apprenticeships; relocation allowances; and reemployment services such as career counseling).

The TAA is not without its flaws. It has earned a bad rap from some on the left as an attempt to cover up grim economic realities, and by some on the right as an ineffective program. But a closer look at the program’s overall results speak for themselves. In 2015, 73% of TAA participants found employment in the quarter after completing the program, with 92% of those who did still remaining in their jobs six months later. Compared to a similar group of long-term unemployed workers who did not collect TAA, workers in the federal program were 11.3% more likely to be employed. Moreover, TAA recipients who completed training and found a job in that field received a $5,000 to $6,000 per year earnings boost.

In short, TAA represents a prescient solution to a looming crisis. It provides a ready-made, comprehensive model for the delivery of assistance to workers who experience a shock from the economy, one that is not only relevant to trade-related unemployment, but technology-related unemployment as well.

As I outline in a new report for The Century Foundation, updating TAA can be done relatively seamlessly, by porting the program’s structure to both trade and technological unemployment, creating a new “TTAA,” so to speak. A new certification scheme could be instituted whereby the U.S. Department of Commerce designates a list of occupations at risk of being automated, and in turn, states, firms, or unions apply for federal help once occupation levels drop below a designated threshold and there is evidence of technology-driven job loss.

While we don’t know exactly which jobs will be replaced by technology, we do know with some certainty the types of occupations that are at risk. By pre-certifying specific occupations, this streamlined process would take advantage of existing expert consensus, allowing us to prepare a more robust and rapid response to deliver support to workers whose jobs are suddenly made obsolete. In this way, if millions of long-haul truck drivers become unemployed due to the proliferation of self-driving fleets, Congress and state governments will be ready to help them get back to work.

TTAA participants would be eligible for similar benefits available in the TAA program, such as wage insurance, subsidized COBRA, and career counseling and job placement services. They could receive up to two years paid retraining with income support so they could pay their bills while also preparing for a new career. Workers in TTAA-certified occupations could even begin this training while they’re still employed, which would give them a head-start if they were to lose their job, in addition to increasing their chances of finding a new role within their existing company. A machine operator in a factor, for example, could be trained to operate a computer-controlled tool that was replacing his old job.

For years, political leaders have recognized the need to expand active adjustment programs, on which other major nations spend 0.6% of GDP, compared to just 0.1% in the U.S. Updating TAA would provide an easier glide path for Congress, since it expands an existing program (something always done easier than creating a new program) and has enjoyed bipartisan support for decades (many dislocated workers live in conservative districts). And, a TTAA would be directly responsive to changing free market conditions, in the same way that unemployment insurance benefits rise in downturns.

Policymakers could start small, too, and develop a TTAA pilot to study the program’s effectiveness. Based on my estimates, a pilot program from 2020-2025 would see roughly 103,000 workers participate, at the relatively small cost to the government of $1.8 billion. Were the program to be successful and its price-tag rise, lawmakers could consider a number of paths to fully fund benefits without adding to the deficit or cutting spending elsewhere. A vehicle-miles tax on self-driving cars, for instance, could be directed toward retraining programs. As Bill Gates put it last year: “The robot that takes your job should pay taxes.”

To be sure, a TTAA program is no panacea for the millions, perhaps tens of millions, of jobs that are likely to be affected by automation and AI. No amount of planning or policy proposals can fully prepare us for what’s ahead; there’s no way of knowing what jobs will be lost, or how many, or where, or when. What we do know is that many Americans will experience job loss as a result: workers will miss out on pay, their skills will become of little value, and some will face a long and difficult road to finding new work.

A TTAA program would make that road as navigable as possible, not only helping workers and their families stay afloat during hard times, but also strengthening our workforce overall and making America more competitive on a global stage. It is a fiscally-responsible and politically-feasible approach, based on a model with a long track record of success.

While we can’t predict our economic future, we can prepare for it. A technology adjustment assistance program is as good a place to start as any.

Andrew Stettner is a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank, and author of the new report, “Mounting a Response to Technological Unemployment.”