Chidera Eggerue, AKA The Slumflower, is a social media star, south-east London homegirl and feminist. She first came to prominence in 2017 when she created the hashtag #SaggyBoobsMatter on Twitter in order to promote the body-positive message that women’s breasts and bodies are fine just as they are. It’s an important idea and antithetical to a beauty industry that berates us for our imperfections. A year later Eggerue published a self-help motivational book, What a Time to Be Alone: The Slumflower’s Guide to Why You Are Already Enough, which entered the Sunday Times bestseller list the week it was published in 2018, when she was 23. In her very pink, zanily illustrated book, Eggerue, a self-styled “guru, confidante and best friend” to her readers, offers advice on self-worth and self-acceptance. An earlier booklet called Little Black Book: A Toolkit for Working Women, by Otegha Uwagba, became a bestseller in 2016, paving the way for Eggerue. This, in turn, was probably influenced by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2014 essay We Should All Be Feminists.

These are unprecedented times for black female writers, in no small part due to the internet. It has reconfigured how we present ourselves to the world at large, as well as bringing previously marginalised social groups and writing to the fore in ways hitherto unimaginable. As a society we are beginning to recognise and take seriously the ills and pitfalls of social media, but it is still the most exciting channel of mass communication since history began.

And these times really are extraordinary. The ripple effects of 2013’s #BlackLivesMatter moment, and the movement that followed, saw renewed interest in writings about race in the US, which spilled over into the UK. We are used to the spotlight on racism being beamed across the Atlantic while little attention is paid to the perniciousness of systemic racism in Britain, about which there is much denial. Yet when #BlackLivesMatter gained momentum, it precipitated an unprecedented interest in non-fiction books by black writers. In 2016, David Olusoga published Black and British: A Forgotten History, which accompanied an acclaimed television series and reached beyond the usual niche market for such books. Reni Eddo-Lodge’s bestselling Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race (which began as a blog post which went viral) was published in 2017. However, while Eddo-Lodge acknowledges African American feminists of yore, she is silent on our own trailblazers. In 1985, The Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain, edited by Beverley Bryan, Stella Dadzie and Suzanne Scafe, recently reissued, was one of the first non-fiction books that investigated the subject. Heidi Safia Mirza later published Young, Female and Black (1992) and Black British Feminism (1997). Much of this history has been lost: it is rarely taught at universities, nor does it appear in the timelines of what is effectively a whitewashed British feminist history.

But all of these recent commercially and critically successful non-fiction books have sent the publishing industry into an unprecedented buying frenzy. Last year, Slay in Your Lane: The Black Girl Bible, by Yomi Adegoke and Elizabeth Uviebinené, hit the shelves, a book that celebrated the achievements of black British women while offering advice on how to get ahead. This summer, Chelsea Kwakye and Ore Ogunbiyi’s Taking Up Space: The Black Girl’s Manifesto for Change was published. It examined the experience of black students in predominantly white higher-education institutions, and also started off as a blog post written when the two women were graduating from Cambridge University in 2018. Television presenter and academic Emma Dabiri is the author of Don’t Touch My Hair (2019), a treatise on black hair and its political, cultural, historical, philosophical and personal resonances. Also published this year was Safe: Black British Men Reclaiming Space, edited by Derek Owusu, co-host of the popular black-focused literature podcast, Mostly Lit. In Black, Listed, Jeffrey Boakye offered a witty and hard-hitting take on black British culture with a quirky dictionary of terms, while No Win Race by Derek Bardowell examined sport and race, family and legacy, spanning three decades from the Brixton riots of 1981 to the EU referendum.

The field had been so arid up to this point that each of these works feels urgent, essential. Perhaps none is more transgressive than The Grassling, by Elizabeth-Jane Burnett, also a poet, whose 2019 “geological memoir” explores the Devon countryside where she was raised. Burnett’s deeply poetic communion with nature reminds me of Ingrid Pollard’s 1988 Pastoral Interlude series of photographs, which captured, radically, and in a way that was ahead of its time, solitary black figures in the English countryside. Similarly, the play Black Men Walking, written by Testament, featured three northern black men who go on walking trips in the wilds of the Peak District – and talk. Seeing black British people, especially men, extracted from their usual depiction in an urban environment makes you realise how limiting that portrayal has been, how black life has become synonymous with the metropolis. Black Men Walking was a refreshing, progressive look at male friendship in a pastoral setting, while Burnett’s memoir connects us at a primal, immersive level to the topography of a country that is as much ours as anyone else’s.

Also off the beaten track is Afropean: Notes from Black Europe (2019) by Johny Pitts, whose travels and encounters with black communities offer a counter-narrative to a continent associated with whiteness. Comparisons will too easily be made with Caryl Phillips’s 1987 pan-European travelogue, The European Tribe. But whereas Phillips’s book is a moving account of the experiences of a black man observing an overwhelming European whiteness more than 30 years ago, Pitts shows us today’s black communities on the continent, and reframes our understanding of it. The books are companion pieces, as well as lessons in history, travel and identity. I ventured on to this terrain in my 2005 novel-with-verse Soul Tourists, creating a fictional black couple who travel across Europe by car to the Middle East in the late 1980s, a journey I myself had undertaken. But books about Europe from a black British perspective, fiction or non-fiction, are hard to find.

¶

Writing is a solitary rather than a communal process, and not all writers are community spirited, but the new, mostly female, young activist writer communities use social media to market their projects. These are twentysomethings who employ the term “womxn”, with its inclusive emphasis on women of colour, queer and trans people. These womxn are not waiting for the establishment to fund or publish them; they are getting on with it themselves by setting the terms of their intellectual and creative endeavours.

I include here the influential gal-dem and Black Ballad magazines, the organisers of the Black Girl festival, Octavia poets’ collective and the Heaux Noire womxn of colour poetry events. Their entrepreneurship and self-determination remind me of the 1980s, when I was their age. Back then, I co-founded Theatre of Black Women, Britain’s first such company, with Patricia Hilaire and Paulette Randall. Out of this community emerged other theatre companies, dance troupes, music groups, publishers, arts collectives. We remade and imagined the complexities of our lives through an art we could call our own. We were a sisterhood, sometimes dysfunctional, not always in agreement, but there was a network of support and collaboration, much as I see with the young womxn of today.

In the early 80s, those of us who wanted to write had to look across the Atlantic for inspiration. While there was a literary lineage of black writers in Britain going back to the 1950s and earlier, they were predominantly male and first-generation. In 80s Britain, the Women’s Press imported the successful books of Alice Walker from the US, but with a couple of exceptions, such as the two novels of Joan Riley, was not interested in black British women’s writing. And while Virago championed Maya Angelou, her homegrown counterparts were mostly absent from their lists.

I remember disappearing between the pages of Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (1999), edited by Barbara Smith, during one long weekend and discovering African American female writers who had the confidence and experience to express their realities through poetry and essays. The fragmentary prose-poetry books of the Jamaican-American author, Michelle Cliff, such as Claiming an Identity They Taught Me to Despise (1980), inspired me to be adventurous with my own writing. In her essay “Caliban’s Daughter” (1991), Cliff wrote that her aim was “to reject speechlessness, a process which has taken years, and to invent my own peculiar speech with which to describe my own peculiar self, to draw together everything I am and have been”.

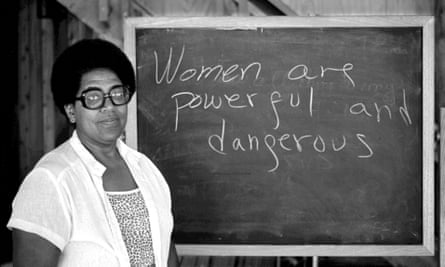

Similarly, Audre Lorde wrote in Sister Outsider (1984): “What are the words you do not yet have? What do you need to say? What are the tyrannies you swallow day by day and attempt to make your own, until you will sicken of them and die of them, still in silence.” She inspired my generation of feminists, much as she now inspires the latest generation, with new editions of her works. I met her when she visited London in the early 80s. She wanted to spend time with young black feminists. At an event at the Drill Hall theatre, with an audience of mostly white women, she demanded that the black women without tickets in the lobby be let in, or she wouldn’t take to the stage.

And how enriching and motivating it was to read interviews with so many great writers in Black Women Writers at Work (1984) edited by Claudia Tate. These African American women spoke of their process and practice long before you could trawl through online interviews and find authors doing the same. I am indebted to the female writers who went before me, whose pamphlets and books shaped me in my formative years and have travelled with me to my many homes over the decades; works that are stained with tobacco smoke, coffee and red wine from the days when I indulged in all three, and, while I have dispensed with thousands of books in my time, these and others from that era I treasure – they still reside on my bookshelves, grouped together to remind me that they were the making of me.

We British female writers were emboldened and encouraged by their literature as we began to produce our own. Anthologies were a good way to start to showcase our burgeoning talents and to give us the confidence that comes with publication. There were several anthologies, such as Black Women Talk Poetry (1987), which featured 20 poets, including Jackie Kay, Dorothea Smartt and Adjoa Andoh, published by the newly formed Black Women Talk Poetry Collective of Da Choong, Olivette Cole-Wilson, Gabriela Pearse and myself; and Watchers and Seekers (1987), a mixture of poetry and fiction, edited by Rhonda Cobham and Merle Collins.

In creating an alternative space for our politicised creativity, we were challenging the status quo. We were too often excluded from white feminist endeavours, just as we were excluded or marginalised from much of the contemporaneous black male arts production. Many of us were queer, either transiently, as it turned out, or for life. This meant that we were more likely to organise as women together, and less reliant on male opinion and approval. Like today’s young arts activists, we were doing it for ourselves rather than hoping to be cherry-picked by this country’s white cultural producers.

We never imagined that we would be taken as seriously as we are at this moment. I was thrilled to win the Booker prize earlier this week, just as I was overjoyed when Lubaina Himid won the Turner prize in 2017 for her exciting, innovative and spectacular work, four decades after she began her career as an artist. Similarly, Adjoa Andoh recently co-directed and starred in the first all-women-of-colour Shakespeare production on a major stage in Britain, Richard II at the Globe.

I wonder what my generation might have achieved had social media been around when we were in our 20s. How would our lives have been enriched by the rapid interconnectivity of today? Many of us have campaigned to improve access to publishing and the arts industry for people of colour for decades, and we are finally seeing the results. I founded The Complete Works poetry mentoring scheme (2007–17), which selected 30 poets to be mentored by many of Britain’s leading poets in order to redress the fact that less than 1% of poetry books published in the UK were by poets of colour. Now that proportion stands at 16% and the mentored poets are winning many top poetry and literature awards.

One thing I have learned is that the future won’t look after itself. We cannot take any developments for granted. If those of us who are considered marginal stop campaigning, we experience social regression. I wonder what will happen if the support systems, networks and development programmes for people of colour cease to exist. The plethora of books currently being published is astonishing, but we must be wary because today’s boom is not the result of a steady, incremental transition. It has exploded out of a void.

Where are its foundations? I have written in the past about fads in the literary world for writers of colour, especially the period in the mid-to-late 90s when there were more young black men and women publishing fiction than ever before, with a tendency towards coming-of-age narratives. By the noughties most of these writers had disappeared.

What happens when the big advances do not deliver on their promise? What happens when second-book syndrome kicks in? What about those who have become authors almost by accident, via blogs leading to instant book deals? We want the field of writing to be wide and abundant, spanning the very young through to the very old. We want our writers to have long careers spent producing work that matures as they do. Yet the emphasis in publishing and the media focuses on the new and the young, although new and young isn’t synonymous with fresh and original. Some of these writers become shooting stars, and when their moment has passed we wonder what happened to them. History tells us that books can too easily disappear from literary and cultural memory, until such time as they are rediscovered, if at all. Alice Walker resurrected the once-celebrated Zora Neale Hurston in 1975, 15 years after her death. Hurston’s books had been out of print for decades. Obscurity has been the fate of too many black female writers.

What is the role of books in our brave new world where knee-jerk reactions predominate, moral outrage is the prevailing orthodoxy and ideas must be compressed to sound bites? Chidera Eggerue, with a hefty 244,000-plus Instagram followers and 79,000-plus on Twitter, sagely advises: “Instagram might shut down one day and suddenly nobody will care about your 80,000 followers. Relevance in the offline world is key.” Conversely, the older writers, artists and activists who eschew social media are missing out on bringing their wisdom, experience and perspective to these debates. It’s an exciting political, intellectual and creative space, and we need to be a part of it – and if not, we must ask ourselves if we are relinquishing our responsibility towards the future.

Eggerue, and other arts activists of her generation, are benefiting from the desire of the multinationals to be aligned with woke young people and to exploit their marketability. The revolution, or rather what we might think of as this countercultural moment where those previously without a platform are having their say, has already been commodified. Those of us who are alert to the capriciousness of this should trumpet a note of caution to those who are swept up in the glamour of the moment. We need to ask ourselves how best we can effect change for our constituencies that is sustainable rather than fashionable. My answer is that the spirit of entrepreneurship, community and arts activism will sustain us long after it’s no longer woke to be “woke”.