The Polar Expedition That Went Berserk

When Antarctica hits you with the worst storm in decades, sinks your boat, and drowns your crew, there’s only one way to react: get another ship and go back for more

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Samuel Massie wasn't superstitious until the day he saw the crows. Two of them, gliding above the Antarctic Plateau. Sure, he’d hardly slept in 48 hours, and it was 60 below, and he was 18 years and three months old, which is to say he knew nothing, and he hadn’t heard from his three shipmates in days. When you’re that cold, that tired, you see things.

There were 188,000 square miles of flat white ice, and Samuel and his 33-year-old captain, Jarle Andhoy, were somewhere in the middle of it. If they didn’t find their way to McMurdo Station in less than a week, they’d be stranded for the entire Antarctic winter of 2011.

Samuel didn’t know that, at this very moment, the Norwegian and New Zealand governments were working to get them kicked off the continent. He didn’t know that Jarle, the man for whom he’d abandoned his life back home in Norway and sailed to the bottom of the world, would soon be engulfed in legal battles. He didn’t know that they were the lone survivors of the most controversial polar expedition since Robert Falcon Scott’s fatal trip, 99 years earlier. That even if they made it off the ice, they’d be flying home to a nightmare of paparazzi and grief. All he knew was that the crows were above him, circling. All he knew was that, for sailors, crows mean death.

At that time, and for years after, Samuel and Jarle were huge in Norway—their stories lingered in op-ed pages and gossip rags alike, although only the occasional, hazy detail made its way across the Atlantic. I followed their saga because Samuel—Sammy to everyone who knows him—and I had attended the same tiny Norwegian boarding school two years apart, and because I related to him. We were both kids who’d sought out deep wilderness as a proving ground, drawn to grandeur and discomfort. But I’d never met Sammy, nor Jarle, until the spring of 2017. That’s when I decided to seek them out, to learn what I could about the boy next door and his evasive, pale-eyed mentor. What I discovered was darker and colder than I could have imagined, a lesson about how one charismatic man can lead his followers into the sea, and the blade-thin distinction between calling yourself a Viking and being one. It’s a story that begins and ends with Sammy Massie.

Sammy was not someone you’d expect to do great things. Later he would learn that there were words to describe his problems as a kid (dyslexia, ADHD, depression), but growing up in Bergen, the middle son of a single mom, he figured he was just a loser. Words crawled on the page when he tried to read them; he dropped out of the tenth grade. His one gift, he thought, was that he was socially adept. He liked girls and partying, and he liked talking to people, because then he felt OK. He felt even better when he sold drugs. (“Everything but needles,” he notes.) He wasn’t happy, exactly, but at least he seemed important.

The only mail he ever got was from his granddad Arne, who liked to travel, so he didn’t know what to make of the acceptance letter that arrived in June 2009. It came from 69° North, a sailing- and adventure-based folk school in Tromso, so high in the Arctic that it seemed exotic even to Norwegians. Folk schools are yearlong recreational boarding schools, remnants of 19th-century democratic idealism, which have developed a reputation as a gap year for aimless granolas. Typically, the letter read, the minimum age for students was 18, but 16-year-old Sammy’s passion for seafaring (which he didn’t have) made him such an ideal applicant that the principal had decided to grant an exception.

Sammy had never heard of 69° North; as it turned out, his mom had sent an application in his name. But the school was desperate for students. It had half the applicants it normally did and was at risk of losing government funding. The past few principals had attempted a series of ill-fated new courses on Icelandic ponies, reindeer-drawn skiing, revue theater. Now, in an effort at recruitment, a new principal, Paal Faerovig, had decided to produce a reality show, Sea Spray, about his students and hire a famous adventurer as the teacher.

At first, Sammy was all set to refuse. “What was I going to do up there, roast fucking marshmallows?” he asked me in Norway last April. Then his neighbor mentioned that he might be able to bang a reindeer-herding chick. It was as good a reason to attend as any other.

A few weeks after the school year started, the celebrity teacher came sailing into the harbor. He was supposed to be famous, but Sammy hadn’t heard of him. All he knew was that the guy had been sailing his whole life, which to Sammy meant that he was probably “a fucking douchebag, a 70-year-old stinking seaman who hated people.”

Except he wasn’t. Jarle Andhoy was young and intensely charming. He talked about girls and put his feet up on tables. He considered himself a modern-day Viking, heir to a fierce heritage of blood and salt.

Jarle had launched his first sailing trip around the world 14 years before, in 1996, when he was only 19. He painted his 27-foot sailboat with sharp white teeth and a grinning shark’s mouth, and named it the Berserk, after the frenzied state in which Vikings entered battle. He shot a TV documentary about his mostly solo, 18-month voyage and soon became a household name, then translated that fame into a career as a professional adventurer, selling TV series and books about his expeditions. In 2002, he sailed as far north into the Arctic ice as possible, and in 2007, he traversed the Northwest Passage. The journeys cemented his renegade status. In 2002, he and his crew members were charged with disturbing a polar bear by singing opera to it. In 2007, he was caught smuggling a wanted man into Canada.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that two people with little regard for the rules would bond. At first, Sammy struggled with life at the folk school. He fumed when his fires didn’t light and his smoker’s lungs gave out halfway up a mountain. But Jarle helped mold his anger into determination.

“At that point,” Sammy told me, “I’d been a problem for everyone my whole life. But Jarle gave me responsibility. It was a chance to impress people for once. He was proud of me.”

At the school, it didn’t matter what a person could do; it mattered what they wanted to do. Partway through the year, Jarle took Sammy aside and invited him to join an expedition to Antarctica. Even Jarle was surprised by how quickly Sammy said yes.

The Berserk launched from Tromso in January 2010. Jarle’s plan was to crisscross the globe for almost a year—Norway to Siberia to Japan to Indonesia to Australia to New Zealand—before reaching Antarctic waters. Once there he planned to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Roald Amundsen’s first successful voyage to the South Pole by retracing the route on all-terrain vehicles. There were only five sailors on the boat, but within seven months of the launch, three people—two crew members and a visitor—had been seriously injured. A lady friend of the first mate fell overboard and woke up in a hospital after four days in a coma; the machinist was attacked in Kamchatka, Russia, and ended up with 11 stab wounds and a broken neck; and another sailor disappeared in Indonesia and surfaced in a clinic with a split face.

To fill his dwindling ranks, Jarle recruited men he met in bars along the way. He was funding the trip in part by filming it for television, so he staged dramatic but fake rescue stories for the new guys. Lennie Banks, a 32-year-old South African surfer, was supposedly floating on a board in the middle of the ocean, caught in a deadly riptide, when Jarle hoisted him aboard the Berserk. Edwin Kumar, a 26-year-old Indian American aerospace engineer, was filmed as if he was trying to escape angry locals through the jungle in Papua New Guinea when the crew found him screaming on a riverbank. “Jarle paid natives to act like cannibals,” chasing him, Edwin told me. “He wanted to portray himself as Captain Perfect.”

Sammy waited for the school year to end, then flew down to join the crew in Darwin, Australia. He took to sailing life immediately. His favorite moments were on deck with the men, shouting songs against the wind. Haul away, you rolling kings… It was an ancient feeling, leaving land, his palms on the mast, clutching this solid thing that could take them anywhere they wanted to go. They were brothers, their voices tangled and deep, and they were splitting the sea.

They played like boys. Lennie instituted a game called Doorknob. (Whenever someone yelled “doorknob,” he could pummel the other men until they touched a doorknob.) They climbed into each other’s bunks and fed reef sharks by hand. Robert Skaanes, the other Norwegian on board, wrestled with a shirtless Sammy and pinned him on the bow. Waves broke over his head, the weight of a bare foot against his chest. “From Berserk you’ll be, from Berserk you’ll stay,” Robert shouted. “You’ll go berserk!” Sammy bared his teeth and laughed and laughed, hair streaming over his face, as seawater filled his open mouth.

They were headed toward the most dangerous waters in the world. With the extra gear, the Berserk was top-heavy—but not, they hoped, enough to tip over and drown them.

They called each other Womanizer, Rocket, Sleepy Sammy. When Sammy contracted chlamydia from a one-night stand in Singapore, they called him Clammy Sammy. They ate pasta and onions every day. They stole Jarle’s sound equipment to record messages and swatted his camera away when they cried.

Captain Jarle was strict, but even that was part of the thrill. He was, he said, teaching the crew to be men. “I want you to do push-ups, not fuck-ups,” he yelled once on an Auckland dock, with Robert and Sammy at his feet, sweating in their polar layers. Robert did 60 push-ups. Sammy did 27 shaky-armed fuck-ups, then tipped over and moaned before managing three more. Sammy had never worked so hard in his life, but he liked it. Maybe, he told himself, he was becoming a man.

After almost a year at sea (half that long for Sammy), they stopped in Auckland during Christmas 2010 to make final preparations for the pole. Edwin “Rocket” Kumar disembarked for good. Jarle claimed that he wasn’t competent as a machinist; Edwin told me that the trip seemed unsafe, and that as the only crew member of color he felt especially vulnerable in Jarle’s plans to land on the continent without a permit. Edwin had been suspicious of Jarle ever since he developed an infection at sea and Jarle denied him antibiotics. “He was like, ‘You’re tough, you’ll survive.’ My leg was swollen like a friggin’ rhino’s leg. I couldn’t walk. Sammy would come and squeeze the pus out.” Edwin says that Lenny wanted to quit, too, but couldn’t afford to. Lenny hoped that going to Antarctica would open up opportunities for him.

Still, Edwin’s departure did little to dull the mood. He was promptly replaced by Tom Gisle Bellika, a 36-year-old fisherman’s son who flew in from Norway and had piloted the Berserk through the Northwest Passage nine years earlier. Gisle was a pink-faced giant in wool fishnets, and he would serve as second-in-command, a responsibility he took seriously. “Sailing the Berserk,” he liked to say, his glass eye fixed on the horizon, “is like fucking a fat woman on a waterbed. You have to find the rhythm, or else you’re just fighting.”

Jarle brought two ATVs for driving to the pole, and the men painted the machines red, with sharp white teeth. They named them Fram and Endurance, after Amundsen’s and Ernest Shackleton’s ships. Sure, the Endurance had been crushed by ice, but most of its men came home safely.

When they left their final port in New Zealand, the Berserk carried five men and ten tons of equipment, including the ATVs, two kayaks, a dinghy, tents, metal ladders for bridging crevasses, food to last them six months, and matching wool socks and skull-and-crossbones hats knit by Robert’s grandmother. They were heading toward the most dangerous waters in the world, where waves could rise 80 feet, three times the length of the 27-foot boat. With the extra gear, the Berserk was top-heavy—but not, they hoped, enough to tip over and drown them. To this day, nobody knows if they were right.

Three weeks out of New Zealand, the Berserkers cheered at their first iceberg, its turquoise base rocking in the dark sea. But soon enough, finding a safe channel even on clear days was exhausting. They worked double shifts as the little boat crossed the Antarctic Circle, the surface of the water crusted with milky scales of ice. The Berserk churned through frozen plates that hesitated, cracked, split. Gisle pushed growlers away with a pole, his body bent over the front rail. Around the boat, swells crashed against icebergs and sank away in skirts of white foam.

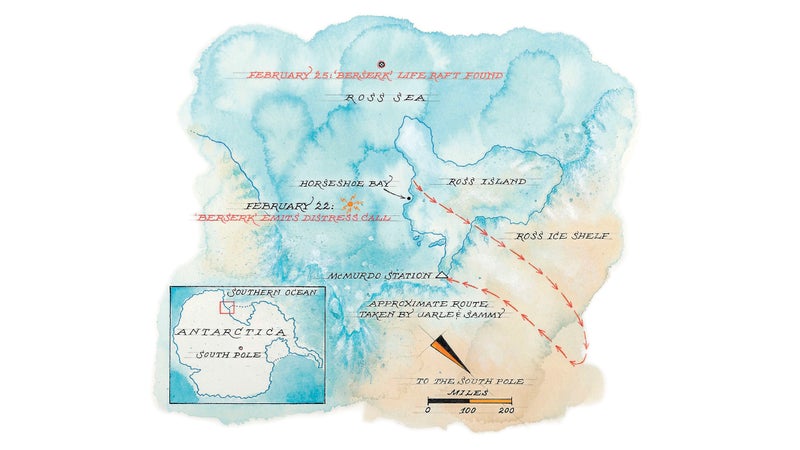

The safest month for overland Antarctic travel is November, the Southern Hemisphere’s equivalent of May, when a bright sun dulls the continent’s worst storms. The Berserk reached Horseshoe Bay, along the Ross Ice Shelf, in mid-February, after other experienced captains had sailed northward for the season. “If I were there, with all my experience in the Ross Sea, I would have been shit scared,” says explorer Don McIntyre, who has captained 55 trips to Antarctica. But the sky was clear, and Jarle decided to tie off to the ice and try to rush through his plan before the season turned. The Berserk would stay here, in relatively safe harbor, while Jarle and a companion drove their ATVs 1,000 miles to the pole. Then the ship would sail 15 nautical miles across the Ross Sea and meet them near Scott Base for the journey north. Jarle chose Sammy to join him on land, maybe because he needed the stronger men to handle the boat, maybe because the kid made for a better story. (He won’t say.)

Jarle and Sammy straddled their machines and gunned it south, leaving the Berserk silhouetted against a pink sky. They drove through the nights, traveling 30, 40 hours at a stretch without rest, racing the winter. At times, spinning in snowdrifts, they averaged less than six miles per hour. It was not fast enough. On their tenth day, the season’s first storm hit from the southeast, wind and snow whipping past at 110 miles per hour. A nearby ship, the Wellington, later reported that it was the worst storm in 19 years.

For Sammy, the storm brought the gift of rest, under a tarp, sucking chunks of frozen salami while six feet of snow fell on him. When he woke up, Jarle was angry. The men on the Berserk weren’t answering the satellite phone. But a friend of Jarle’s in Norway told him that the Berserk had fired its EPIRB—an emergency alarm that sends a rescue signal—around 5 P.M. on February 22, just one day earlier. For some reason, the men had left their safe anchorage in Horseshoe Bay and sailed or drifted 18 nautical miles into the thick of the storm.

“What does that mean?” Sammy asked. As if Jarle could answer.

So they called their mothers, who’d thought they were dead. All of Norway thought they were dead. The storm had made the expedition a media obsession: “Berserk Missing” was on the front page of nearly every major newspaper in the country.

The Berserk was gone, they were alone, and in just five days the last flight of the year was leaving Antarctica from McMurdo Station, the American research base. Sammy isn’t sure how close they came to the pole, but it had taken them 11 grueling days to get wherever they were.

“I hope you’re rested,” Jarle shouted, mounting his machine, the white plateau endless in every direction. “This’ll be a hell of a race.”

They didn’t stop to rest or eat, clinging to the ATVs for 48 hours at a time. Sammy saw things: The teeth of the Berserk grinning through a white storm. The lurch of an iceberg slicing the hull; water filling the cabin, covering the cots and dirty dishes; the ragged world map. Onions floating. His tears froze to his face. Hours passed in a rattling daze, punctuated by stops to refill diesel and updates via satellite calls to the New Zealand coast guard and authorities at McMurdo.

Through the sat phone, they got news: a search crew had found a lifeboat.

News: it was empty.

News: its registration code matched the Berserk.

News: Sammy found chocolate in one of his sleds. It broke in his mouth with a frozen crack. He could feel the energy streaming into his hands, his feet.

What if the Berserk was fine and the lifeboat just got knocked loose by a wave? What if the mast broke, and Lennie and Gisle and Robert were drifting, waiting to be rescued?

One more day on the machines, in that endless roaring moment, and then mountains rose and a city came toward them. Metal buildings painted dull colors, labs and dormitories. As soon as they arrived at McMurdo, security personnel escorted the Vikings onto the last flight of the season, a military plane already humming on the runway. Jarle’s frostbitten cheeks were peeling off in meaty chunks. Sammy felt as if invisible hands were shaking his body, rattling every bone.

Sammy didn’t know that, in choosing to launch an expedition without the approval of the Norwegian Polar Institute, which governs citizens’ activities on the continent, Jarle had become the first European to break the 50-year-old International Antarctic Treaty. Military satellites had tracked their every movement for weeks. Sammy was barely alive, he was 18 years and four months old, and his problems were only starting.

When Sammy and Jarle landed in Christchurch, New Zealand, reporters swarmed the runway. How do you feel? Are you optimistic? What’s the first thing you’re going to do when you get home? Sammy heard himself say something about holing up in a dark room with his PlayStation. Why did he say that? He tried again. “I just lost three family members.” That was better. That was true.

Back in Norway, Jarle and Sammy flew to their homes, near Oslo and Bergen. They talked on the phone often, and together they clung to the idea that Robert, Lennie, and Gisle were floating on an incapacitated Berserk, waiting to be discovered somewhere on the ocean. The boys had enough pasta and onions to last for months. They could take care of each other, sing together, drift north toward safety.

But when he hung up the phone, Sammy was alone, even with his own family. He felt hyperaware of his facial expressions, startled by the feeling of touching his own skin in the shower, jumpy at the sounds of doors. When he walked down the street, strangers hugged him. When he bought his first-ever legal beer, the cashier did a double take and said, “You’ve been in the newspapers a lot lately, and now you’re out partying?”

With a coast guard ship close behind, Jarle popped a can of spray paint and scrawled “BORN FREE” across the sail, scrambling in a haze of red mist.

It was Sammy’s granddad who saved him. Arne was a ladies’ man in his late seventies, wry and charming. He wanted to paint his cabin, a fishing shack on one of Norway’s westernmost islands, and Sammy joined him. Sammy had never gone to the cabin voluntarily before, but there on the island of Hellesoy, without his cell phone or the Internet, surrounded by water, he felt like he could breathe again. “We sat there. Drank tea. Walked to the lighthouse,” he said. “I isolated myself. That was the time when we got to know each other. I feel lucky to realize how important my granddad is, now, while he’s still alive.”

They didn’t talk much about the Berserk, but they talked about dreams. Arne had wanted to ride a motorcycle through South America. He wanted to be a whaler in the Southern Ocean, to join his friends in adventure, but a priest had convinced him to enlist in the military instead. Sammy may not have made it to the South Pole, but Arne hadn’t, either.

Sammy stayed on Hellesoy for four months. Every day it seemed less likely that his lost brothers were alive. On the mainland, Jarle faced public scrutiny. Why had he chosen to stop in the most dangerous waters in the world? Why hadn’t he established a plan for search and rescue?

In 2011, the Norwegian Polar Institute reported Jarle for the illegal trip, and he was charged with breaking the country’s Antarctic regulations. In response, he offered up a rhetorical false choice: he could pay the $3,600 fine, or he could look for answers about the Berserk’s movements in the days before the tragedy, do it for the boys. Which was more important? He accused the New Zealand coast guard of covering up vital information from the search and of stealing the equipment he’d left in caches for the drive from the pole back to the boat. Lenny’s twin sister and Gisle’s mother petitioned Jarle not to make a TV documentary about the trip, saying that he had refused to share information with crew members’ families and would be “profiting from the deaths of our brothers and sons.” Jarle argued that the voices of the dead needed to be heard—never mind that, in many cases, the footage had them performing scripts he himself had written.

One night in the winter of 2011, when Sammy was home in Bergen, his phone rang at 1 A.M. It was Jarle. His voice sounded different, excited. He said he’d bought a boat in New Zealand, a 54-foot yacht called the Nilaya. He wanted to take it back to Antarctica. He wanted to look for answers—#fortheboys, as he’d written again and again on Facebook, updating his fans. Now he wanted to know: Was Sammy in?

For months, Sammy thought he’d never get on a boat again. He’d certainly thought he’d never go back to Antarctica, though he’d seen it in his mind every day. But he also wanted “to not be controlled by the tragedy,” he told me. “To shut it behind me. Closure. I wanted closure.” He wanted to do more with his life than be the boy who survived something terrible.

In late December, Jarle and Sammy flew to Auckland, where they would leave once more for Antarctica. Sammy says that immigration authorities caught wind of their plan when they noticed that his girlfriend, who flew down for the launch, had an awful lot of outdoor gear in her luggage. The yacht formerly known as Nilaya, now renamed Berserk, took sail in a mad race for international waters. With a coast guard ship close behind, Jarle popped a can of spray paint and scrawled BORN FREE across the sail, scrambling in a haze of red mist. They made it out of New Zealand waters, 24 nautical miles from shore, just minutes ahead of the law.

“Sailing again was very right, very wrong, very scary. All the feelings you can imagine,” Sammy recalled. The waves, the scales of floating ice, the rocking sickness of the sea. So many things could be signs, omens. But when they came to Horseshoe Bay, where they had last seen the Berserk, they found nothing. They sailed seven nautical miles, to the spot where someone on the Berserk had set off the EPIRB, where Robert and Gisle and Lennie had asked for help, where the Berserk had, for reasons that no one will ever know, navigated into a deadly storm and vanished forever. The Surviving Berserkers threw letters overboard, and the pages floated alongside them. It was time to go home.

It took me weeks to reach Jarle. When I did, I mentioned that captain Don McIntyre, one of the most accomplished seamen in the Antarctic, spoke highly of him. “Don McIntyre is a stuck-up self digging fool who was the first to judge fallen men,” Jarle replied within hours. He would be going to court soon, he wrote. “I can talk to you then on general terms.” The trial was the latest in a tangled five-year battle with the Norwegian Polar Institute, which had reacted to Jarle’s breaches of the International Antarctic Treaty by attempting to enforce it through the country’s own judicial system. After Jarle’s fruitless search for the Berserk in 2012, the police fined him approximately $5,600 for failing to obtain a permit. They took him to district court when he refused to pay; his appeal to the supreme court was rejected.

Not only did Jarle continue to ignore the fine, but he thumbed his nose at the NPI by launching another unapproved 2015 Antarctic expedition, crewed by a comedian and a rock guitarist from the Norwegian band Backstreet Girls. Polar authorities only found out about that trip when they read about it in the newspapers; they again attempted to fine him for his failure to get a permit. Though he was found innocent upon return, the slighted NPI appealed the ruling to a tribunal, which was scheduled to begin on April 6, just four days away. I flew to Tromso immediately.

In the spare Arctic courtroom, 39-year-old Jarle—murine on camera, handsome in person—wears sneakers with torn dress pants, a snug shirt half unbuttoned over a black T-shirt that reads BERSERK. His hair sprouts in uneven tufts, with two tiny rat tails hanging over his collar. He cut it himself, though he didn’t think anyone would notice, just like most people don’t notice the white strands at his temples. He is at once magnetic and defiant, unwrapping gum while the judges address him, taking selfies with fans outside the courthouse. When asked why he didn’t buy insurance this time, he claims that’s “like asking for insurance to jump out this window and land head-first on the asphalt.”

After the three-day trial, Jarle texts that I should meet him “in the yakuuuuuzi” at the Clarion Hotel, and I searched three of them before finding the right one, an old seaman’s haunt overlooking the snowy harbor that once served as the heart of the country’s whaling and sealing trades. Jarle and his crewman Jaffe, a firefighter who served as a witness in the trial, meet me in their boxer briefs, and I try not to blush when I strip to my underwear in a corner of their room before joining them in the hot tub on the hotel’s fifth-story balcony. I would prefer to talk fully clothed, but this feels like a test.

One of Jarle’s terms for talking to me, as it turns out, is that he won’t speak on the record about the expedition. Instead he spends the next three hours chatting with two young American men in the steaming tub. The guys are self-proclaimed liberals, but after a couple of beers they begin slipping into his orbit.

It’s fascinating to witness Jarle’s dudely seduction firsthand. This is his magic: to represent an incandescent masculine freedom, drawing fans and sailors with the idea that the whole world is theirs, gated only by bureaucracy and their own urban cowardice. That night, cheered on by adoring strangers, he drinks until the ground rolls like the sea.

A week later, the judges come back with a verdict: guilty of traveling to Antarctica without a proper license. Jarle receives a 30-day suspended sentence and is fined an additional $7,000. He announces immediately that he won’t pay. He’s an activist, and the court is just one more barrier, one more step in his fight against the oppressive scientists at the Polar Institute. A Viking relies only on himself. A Viking makes his own rules.

“That’s where me and Jarle split,” Sammy tells me over the phone. “He’s chosen the path of lawyers and court cases. I understand him, but he’s… He started to, like, annoy [the authorities] on purpose.”

Two days later, I meet Sammy for the first time on a loading dock outside Oslo, past stacked containers and a wary security guard. “Friend!” he shouts.

Sammy’s hands are greasy, so he hugs me with his elbows instead of offering a shake. He wears a blue T-shirt and a newsboy cap. He is clean-shaven, filthy, beaming.

Sammy’s fame has grown. Both he and Jarle were asked to join Skal Vi Danse, the Norwegian version of Dancing with the Stars. Jarle declined; a Viking doesn’t dance. Sammy thought about it. The opposite of Antarctica was the North Pole, but another opposite was Skal Vi Danse. He found that he loved dancing—the challenge of control, the sensuality—and made it to the show’s semifinals as a crowd favorite in 2015. Then he came back to host a second season. At 22, to the delight of Norway’s gossip mags, he married his cohost, Elsa Maria, who is 11 years older. His granddad was best man.

Still, Sammy couldn’t stop thinking about death. When he wasn’t working on Skal Vi Danse or writing books or speaking at schools, he volunteered at a hospice, talking with residents. Recently, he admitted to me, he smuggled a woman out of the facilities so she could see the ocean one more time. Her favorite candy was Fox, a kind of chewy lemon licorice, and her favorite song was “I Feel Good.” So they drove to a private beach, blasting James Brown and munching squares of Fox. They sat on the sand and watched the waves for so long that they missed dinner. But it didn’t matter; they were full of candy. The woman died two days later.

Sammy is on the loading dock now because he’s co-leading a program in which recovering addicts and other troubled men learn how to repair and sail boats. It is called Hold Fast, just like his 2014 memoir, and he’s been involved for two years, ever since Rune “Super’n” Olsgaard recruited him. Super’n is a fifty-something Hells Angel who once spent a year in solitary confinement for a murder he didn’t commit. He’s also the old first mate of Jarle’s who got stabbed in Kamchatka on the 2011 Berserk expedition, thus avoiding the fateful trip south.

The Vikings perch on scaffolding, sledgehammers cracking in time with black metal from a boom box. The copper gleams, a bright wide line. When the sun hits, it’s blinding.

Super’n sold his Harley Electra Glide to buy the program’s first yacht, a 40-foot Colin Archer replica. They then traded that boat for the one that stands before us on the loading dock, a 60-foot seal-hunting ship built in 1907. They’re calling it the Black Swan, and it is, in essence, the anti-Berserk: equipped with survival suits and rescue plans. “Born free, live free, all that kind of shit,” Super’n says. “It’s fine to do that, but buy the fucking insurance.”

In the past nine days, the Vikings in training have replaced the rotted bow and four boards in the hull and scraped the paint down to wood, and they’re now fastening copper plates along the waterline to shield the pine belly from razor-thin ice. They perch on scaffolding, sledgehammers cracking in time with black metal from a boom box. The copper gleams, a bright wide line. When the sun hits, it’s blinding.

“My arms haven’t been this tired since I discovered masturbation!” hollers one of the men, a post-goth Viking with metal cuffs and a New Jersey accent.

Sammy stands on the dock below, spreading tar, humming a waltz. He relates to these men; he remembers being in their situation. When I bring up his past, he grins. “I was hella good at dealing drugs!” Later I mention that I saw one of his dances, in which he wore suspenders. “I like suspenders,” he says happily. “They’re good fun.”

Basically, Sammy likes everything now. He has to: positivity was a conscious decision he made to keep himself alive. One day on the Berserk, he was throwing up on his pants, wanting to jump overboard and drown, when some deep, buoyant survival instinct roared to the surface. Throwing up! It’s just like eating, but in reverse! And sure, he couldn’t keep food down, but at least he had food. And when he opened his eyes in the morning, he could see! “I am always experimenting with how to lift people up,” he tells me. If this incandescent optimism ever annoys his friends, it’s only on land. At sea, sick and exhausted, nobody minds a bright face.

The men work in shifts through the night, and in the morning they’re sleepy, the cabin rich with the smells of bodies and breath. For breakfast they eat 24 eggs and drink three cartons of chocolate milk. Today’s a big day. The 50-ton boat slips on tracks into the fjord, silent in the blue morning. Specks of tar bloom on the smooth water, then shrivel away; oil spreads in tendrils off the hull. There’s a moment, breathless, when we all realize we’re floating. The Black Swan putters toward downtown Oslo, passing the pearly opera house that reflects on the water, the orange cranes lifting in the dawn, the bulbous cruise ships. It docks easily, the men working in unison.

“There was no screaming,” one of the Vikings observes.

“No,” says Super’n. “Screaming is only the Berserk way.”

Proud as he is, Sammy won’t be joining the Black Swan’s maiden voyage. He has his own trip planned. He’s already packed. He’s just waiting for his granddad to plant the potatoes.

For years it’s been gnawing on him that he never actually made it to the pole and that his granddad gave up on his own dreams of exploring. It’s just that now Sammy’s old enough to captain his own ship, and to take his best friend with him. First he and Arne will fly to South America, where Sammy’s already bought a motorcycle with a sidecar—“the stroller,” Arne calls it, laughing—and they’ll joyride south, past the gauchos and the volcanoes, down to the tip of Chile, where a new (insured) sailboat is waiting. Then: Antarctica, past the seas where Arne’s friends whaled 60 years ago, where working-class Norwegians lived farther south than the rest of the world’s great explorers could even reach.

When they reach the frozen continent, they’ll travel by skis, nothing motorized. “We’re from Norway,” Sammy tells me. “The point is being in contact with nature. I’d use sled dogs, but it’s illegal. They eat penguins or whatever.”

He’s been working out; he’s stronger than he used to be. He’ll pull his 82-year-old granddad on a sled if he has to. And they’ll make it to the South Pole this time, together. For Arne. For Sammy. For the boys.

Blair Braverman (@blairbraverman) is the author of Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube and writes Outside Online's Tough Love column. Tomer Hanuka (@tropical_toxic) is an Outside contributing artist.