Where Have You Gone, Dale Murphy?

As a nation of Hall of Fame voters turns its lonely eyes to him, the questions linger: Should a man who never juiced be rewarded for the home runs he never hit? And what if our love was never really his reward?

This story appears in the Heroes Issue of ESPN The Magazine. Subscribe today!

The boy focused his hurt and longing into his love for a baseball player named Dale Murphy. These were feelings he couldn't process or even understand until years later, but he found comfort following the Braves. Joel Bronson was his name. He could have been any kid born between 1972 and 1978 anywhere within reach of the TBS satellite but most likely in the Southeast. Joel grew up in Florida, raised by a single mom. He longed for a relationship with his absent father and filled that hole with admiration for Murphy. Joel loved Dale. He watched all the Braves games on TBS. Finally in 1991, after Murphy had been traded and Joel's grandmother had died, he sent Murphy a two-page letter. Normally he wrote chicken scratch, but on this one he worked hard on his handwriting. Joel told Murphy he'd been a "father figure" to him. Teenage boys often hide their weakness behind subwoofers and cigarettes, but Joel shared his grief over the loss of his grandmother. The pain poured out, and he felt better.

Joel became a teacher and coach. He kept communing with his younger self, shelling out money to attend Braves fantasy camp or to purchase something called the MVP Experience, where fans got to watch a game in a suite with Dale and Nancy Murphy. For years, he'd show up at these events until he actually came to know Dale a little bit. They even exchanged numbers. Last year he decided to go to Braves fantasy camp one last time, now a 44-year-old man with three disintegrating vertebrae who needed physical therapy several times a week just to stay on the field. He wore No. 3.

The first night, with everyone meeting at an Orlando bowling alley, he texted Murphy to see if he needed a ride. To his surprise, Murphy said yes. Joel and his roommate pulled up to an Orlando hotel. Playing coy, Joel didn't tell his passenger where they were going or that he'd gotten to know their boyhood hero. Sitting in the back seat, his roommate saw a tall, familiar man loping out of the sliding doors, getting closer and closer to their car, until he realized that Dale F'n Murphy would ride with them.

"You got to be kidding me!" the roommate blurted.

Murphy got into the car, and Joel told him stories about his childhood. Soon they arrived in the parking lot of the bowling alley. Murphy smiled.

"Hey, I got a story!" he said.

Dale explained that his wife, Nancy, had found old fan letters while cleaning out their home and that he'd taken a picture of one in particular. Murphy handed his phone to Joel, who didn't immediately recognize the careful, neat handwriting in the photo. The letter was dated June 17, 1991.

"Who wrote this?" Joel asked.

"You did," Dale Murphy said.

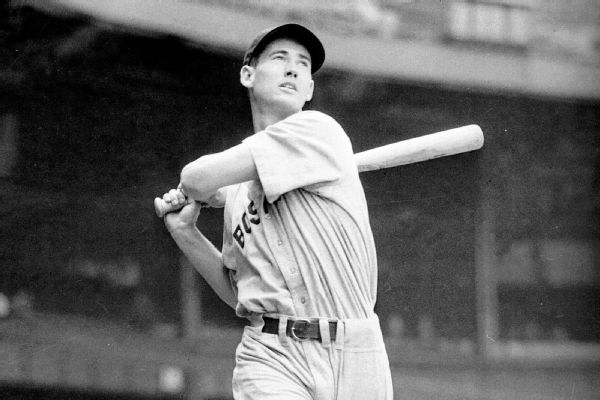

Murphy tried to keep his focus on his family during his playing days -- but didn't always succeed. Getty Images

I SENT A letter too.

Joel and I are two of the thousands of TBS Kids, or Generation Murph, or whatever you'd like to call us. Most of us were born during the presidency of Gerald Ford or Jimmy Carter, and we fell in love with baseball watching the Braves on the Superstation. We hung the posters of the lanky center fielder in loopy midswing stride -- too wide a loop and too long a stride, time would prove -- and we wanted to grow up just like him. We told him so. Our letters arrived at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, 50 or more a day for a decade, as Murphy perennially battled Mike Schmidt for the NL home run title and won back-to-back MVP awards, one of four outfielders in baseball history to accomplish that. We read the stories about Murphy's kindness and charity, how he didn't drink or smoke or curse and how he signed every autograph. We imagined meeting him over big glasses of milk and talking about his moonshot home runs. Around the South, we fought over who'd wear No. 3. For Ron's Heating & Air in Clarksdale, Mississippi, I won the fight. Everyone on the team had his name ironed on except me; my parents forbade me to get "Murphy" on the back, and I told them I'd rather have no name at all if I couldn't wear the name of my hero. My jersey stayed blank.

Generation Murph has grown into middle age. We are 35 years removed from his peak as a player. He lives mostly anonymously in Utah with his wife and eight grown children. The last time he entered a news cycle was five years ago during his final year of regular eligibility for the Baseball Hall of Fame. He never really came close to selection and dropped off the ballots, despite his two MVP awards, his 398 career homers and his status as one of the most beloved players of the early and mid-1980s. You either idolized Dale Murphy or you don't remember much about him.

"There's a very specific historical and cultural moment that he's forever associated with," says his oldest son, Chad Murphy. "For the Southeast in particular, it was something larger than life. There was some mythmaking, but the reality was, that was him. That was just literally him."

Next year Murphy will be eligible again for the Hall of Fame through the Eras Committees, composed of journalists, executives and former players. There's a statistical case to be made for his inclusion in Cooperstown, but to past voters, his numbers have fallen just short. That's what makes his candidacy so interesting. The steroid era ballots prove that morals matter. The voters believe a person can be bad enough to discount statistics that exceed any barrier to the Hall -- yet they don't believe someone can be good enough to elevate stats that land just below. "My dad is the perfect case study," Chad says. "You open it up to complex moral questions that people are uncomfortable with."

He isn't complaining, more fascinated than anything else. He's got a Ph.D., and this kind of anthropology intrigues him. He calls it a "bigger American question." Both of us talked about a culture that doesn't seem capable of acknowledging right and wrong -- a culture that still believes in bad people but no longer believes in good ones. "Do we value performance at all costs," he asks, "or do we want to be more holistic in how we value people and their accomplishments?"

DALE AND NANCY Murphy live on a manicured corner in a Rockwell American town. Alpine, Utah, has a white gazebo. Their house is nice but not extravagant. They greet me together at their front door. The only clue inside that a former ballplayer lives here is a photo of Dale at spring training holding two of his grandsons, all of them wearing matching No. 3s. His two MVP trophies are in a closet upstairs. Their eight kids are grown -- Travis, their special-needs son, still lives with them -- and they're looking to downsize. Together, they're hilarious, with Nancy alpha-momming and Dale shrugging and laughing and raising his arms to the sky. The kids compare them to the couple from Modern Family.

"They all say Dale and I are like Phil Dunphy and his wife," she says. "She's a little high-strung, and he's a little forgetful."

We sit down, and they describe how Generation Murph looked from the inside, what they experienced in the gaze of all the TBS Kids. His sudden fame startled them. Chad would see his dad on TV and walk around to the back of the set to look for him. Fans knocked on their door, and at least one walked uninvited into the backyard. With a new kid on the way seemingly every season -- Nancy had two miscarriages, so that's 10 pregnancies in 13 years -- her father closed his medical practice and her parents moved to Georgia to be close. Their Mormon faith helped them navigate the chaos.

The family often waited in the shadows for an hour or more as Dale signed autographs and visited with kids. During one long autograph session, Chad looked at his mom and asked, "Is Dad going home with them?" That hit Dale hard and would never leave him. It's strange that being nice could be a problem, but it became one. Being kind is easy and a huge dopamine hit. For Murphy, the invitations were endless, which meant endless opportunities for immediate positive feedback. He knew people saw him as the guy who said yes, and he didn't want to tarnish that reputation. Nancy found herself eavesdropping on phone calls from the other room, trying to suss out what he might be agreeing to so she could manage it. Once she heard him a few days before Thanksgiving talking to a Boy Scout leader about camping on Thanksgiving eve on top of the Empire State Building. He did eke out a no, with her just shaking her head. "We had our share of conflicts," Nancy says. "For us, it was Dale saying yes to everything."

"Nancy and I were always battling that," he says. "I was trying to say yes. I knew what I meant to those boys. And Nancy would say, 'No, these are the boys.'"

"When you say yes to that thing," she says, "you're saying no to us."

Murphy had to balance the wishes of his eight kids (and now 12 grandchildren) against the earnest pleas of millions of adoring fans. Preston Gannaway for ESPN

HE MADE A real effort to keep his attention inward on his family. They sold their house in a regular neighborhood after the 1984 season and moved to a 10-acre farm behind a gate. "Murphy" wasn't on the mailbox. Pines and oaks hid the house. They had a pond with two swans. Dale and his family worked together in the garden, growing things like tomatoes, cucumbers and squash. He built them a scarecrow to protect the crop.

In public, he was still Dale Murphy: seven-time All-Star, winner of the 1988 Roberto Clemente man of the year award.

In private, he was Dad.

Nancy kept reminding him to re-center. There's a picture he thinks about a lot. It's a candid of him in the bowels of Candlestick Park on a pay phone. The game is about to start, a crowd cheering and waiting to see its heroes in the flesh, but he's calling Nancy and his family. He's calling home.

He didn't miss a game between 1982 and 1985. His career began a sharp decline after 1987. His home runs slowed, but the strikeouts did not. He was traded in 1990 to the Phillies, hoping to get out of what he called a "rut." His longtime rival Mike Schmidt even sent a videotape that showed some ways of dealing with the effects of age on a swing. Three years later, he took a pay cut to move to the expansion Rockies. Injuries and a staph infection left him hobbled, a shell of his former self. Halfway through the season, and playing in the thin air just two home runs shy of 400, he couldn't do it anymore. A lot of guys would have stayed to get those last two homers, but he missed his family.

He called Nancy and told her he couldn't even run. "I'm coming home," he said.

Now, 25 years later, her voice cracks telling that story. She was pregnant then with Madi, their youngest.

"I can't even explain it," she says. "There are no words. I had a weight lifted off my shoulders: 'Oh, thank you, thank you ...'"

They left Georgia and, after managing Mormon missions in Boston, settled in Utah. Dale faded from the spotlight.

His whole life he'd been a ballplayer.

"He was really trying to find himself," Chad says. "'Who am I now?'"

Dale decided he was a father and devoted himself fully to the kids. He didn't get crazy rich, but he'd made enough as a player to never miss a moment now as a dad. The madness of their home became his life. Eight children, seven of them boys, all big enough that three would play college football. Every day, they collectively drank a gallon of milk and ate three dozen eggs. The boys shared underwear and socks, picking them out of a massive bin. Holes got knocked in walls. Dale would find a Nolan Ryan-signed baseball in the bushes. Nancy did 10 loads of laundry a day. They tried to support everyone's dreams. "The thing we figured out as parents," Nancy says, "you gotta let them find what they love on their own. The thing you have to tell your child to stop doing to go to sleep, that's the thing they love."

Dale drew with his son Tyson or called former NFL players for advice for Jake. He'd come home with records he thought were cool, listening to Death Cab for Cutie because he thought Chad might like them. Chad didn't really like Death Cab, but even then he realized that his dad was trying to find common ground they could share during turbulent teenage years. After Dale retired, Chad told his father he wasn't going to try out for the basketball team. He had other interests. He liked music.

That night, Dale took Chad to a store and got him an electric guitar.

Murphy hit 398 career home runs, nabbed two MVP trophies, and ended his career as a hero to millions, including the members of R.E.M. Rich Pilling/Getty Images

IN THE YEARS after baseball, the Murphy kids don't remember Dale bringing up the Hall of Fame, and with his next window of eligibility coming soon, it remains other people who talk about it most often.

There's no precedent at work, or one to be set, by his candidacy. He's an outlier. He finished his career in the steroid era, the exact kind of player who would have benefited greatly from some anti-aging elixir. His decline happened as the Bash Brothers were born. He remembers sitting in the Braves' clubhouse with Glenn Hubbard and talking about players juicing. Hubbard turned to him and said, "You know how many home runs you could hit if you got on steroids?"

If baseball wants to wash itself clean from steroids, the best way to do it isn't to keep Bonds out of the Hall but to let Murphy in. Induct cheaters but also celebrate Dale Murphy for his 398 home runs and for the dozens he did not hit. He finished just two short of 400, and only four eligible players not linked to steroids have 400 or more homers and are not in the Hall. None was ever MVP. Murphy's recognition is a vote about the culture we want. That's the point Chad Murphy made five years ago in an open letter to Hall of Fame voters. He titled it: "Making the HOF Case for Dale Murphy, or, The Guy Who Changed My Diapers."

In Dale's last year of regular eligibility, his kids all got involved in big and small ways. They tweeted and gave interviews. Chad's letter went viral, and his argument helped drive Murphy's vote percentage higher than it had been in 13 years. Taylor Murphy started an online petition. He printed the names and gave them to Dale, to say: All these people love you. His children's table-pounding felt like the greatest validation of Dale's choices about focusing on his family instead of his fame. In the end, getting in didn't matter nearly as much as seeing how much his children wanted him to get in.

"What the kids did, it was the most emotionally moving time for me as a father," he says. "All those years of saying our family comes first ..."

"... it was about the Hall of Fame," Nancy says, "but it was more about how much they loved him."

Tyson Murphy, a successful video game artist, drew a comic strip that ran in USA Today. Dale says opening the email and seeing the attached drawing remains one of the great milestones of his life, like his wedding day or the birth of his children. The first four panels show Murphy in his Braves uniform holding a bat and signing autographs and looking out from magazine covers. Tyson wrote: "When I was younger, my dad brought cities to their feet. He inspired millions. He was a hero."

The last panel shows an enormous dad and a wide-eyed boy drawing together at a small table.

"But he was more than that to me," Tyson wrote. "He was my dad."

DALE AND I meet in Atlanta on a spring evening and walk to his restaurant, located near the Braves' new ballpark. Murph's has been open a year, part of Dale's attempt to occupy his time now that the kids are out of the house. Truth is, he likes it most because he gets to walk through his dining room and greet his fans, who are always happy to see him. Tonight, within minutes, a grown man tells him that he wore No. 3 in Little League. Someone surprises her husband with Dale on FaceTime and her husband cries.

"It hits you harder," Dale says. "I've got 12 grandkids now, and when people come up to me and share stories, it's hard to put into words exactly what an honor it was to be part of their lives."

He's stopping and starting, searching for the words.

"I'm very thankful," he says. "I'm thankful for that chance to be their ..."

His voice trails off. He can't bring himself to say "hero."

“Dale is definitely one of the only people we trust to baby-sit.”

- Murphy's daughter-in-law Kelsey"When we both turned 60, it really hit me," Nancy says, "and I talked to Dale about it. You look back and you say, 'OK, oh, I get it!' Like, everything we did was putting a brick into building this world ... this life for ourselves. You know? We build this life together. And we have these amazing kids and this beautiful family. I was telling one of my kids, when you stay up late at night talking a child through a problem, you might feel like that time was wasted. It's not. It's one of those bricks that you're putting in your life. And you get to 60, it's so satisfying to look back and say, 'We built this together.'"

He's 62 now. The kids are funny and well-adjusted. They're high achievers. Three sons made it into NFL camps; the youngest just signed with the Rams. One is getting a business-and-law degree from BYU. One is the art director for Riot video games in LA. Another is a professor at Oregon State and an author of comic books written under his pen name, Lord Birthday. (He has 200,000 Instagram followers.) The youngest, Madi, just got her first job and is so much like her father. She too lights up a room.

After years of focusing inward on his family, Murphy is finding he enjoys being remembered. He likes the card shows. On a family vacation to Disney World, his kids spotted a man wearing a Braves No. 3 jersey and goaded Dale into introducing himself. He never would have done that 20 years ago. "It has been interesting to see him learn how to manage the Dale Murphy Persona," Chad says. "It's this ghost of himself that means a lot to people."

We leave the restaurant and walk across a footbridge toward SunTrust Park.

We pass a billboard for a concert.

"Jason Isbell's coming," he says. "Isn't he something?"

Turns out, Dale liked those records he bought to find a common interest with Chad. Today he is a huge indie-rock nut, which surprises no one more than his own children. On his old blog, he wrote about mashing together Abbey Road and Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. He's gotten to know the guys in Wilco and R.E.M., and Chad once sat at a Mexican restaurant in New York with his dad, Peter Buck and Michael Stipe, trying to process how his square Mormon father now ran with rock stars. The members of R.E.M., of course, came of age in the late '70s and early '80s in Georgia, which makes them prime Generation Murph. Bassist Mike Mills wrote a song about Murphy's failure to get into Cooperstown: "Forget all the liars, all the Sosas and McGwires ... I wanna see Dale Murphy in the Hall of Fame."

"He said it's a great punk rhythm," Murphy says.

Of her family, Nancy says that she and Dale put "a brick into building this world. ... You get to 60, it's so satisfying to say, 'We built this together.'" Preston Gannaway for ESPN

A WEEK LATER, on my last day in Utah with the Murphy family, we drive for lunch up into the fog past a riffling trout stream to the Sundance ski resort. The air is bracing. We hear birds singing through the timberline. Dale likes it up here. Just the quiet and the separation. He used to have to look hard to find silence in the circus of his life, but the kids have moved out. Now it's just Dale, Nancy and Travis.

At the restaurant, we find a big round table in the middle of the room.

Soon Taylor comes in with his family.

"Hey, bud!" Dale says with a grin when he sees them.

"Hey, Dad!" Taylor says.

Dale swoops up the little boy, Hollis, and takes him to the fireplace in the center of the room, pointing at the glowing hearth and making crackling fire gestures with his hands. Because I'm here, everyone rushes to tell Dale stories, which makes the enterprise worth it, because he's forced to sit there and take the compliments. "The one thing I can contribute," his daughter-in-law Kelsey says, "is that he is genuinely the sweetest grandfather I've ever encountered in my entire life, and that's including my dad."

"The kids love him!" Nancy says.

"He is definitely one of the only people we trust to baby-sit," Kelsey says.

"If Nancy's with me," Dale says, trying to steer the attention away.

"You don't get bored," Nancy says. "You'll just sit there forever with them and just play with them."

"That's because I'm just a kid," Dale says.

They tell a story about one of the granddaughters with Dale, who loves inventing activities. He took her to the store to buy seeds, and then they came home and planted marigolds together, a little kid and a lanky ex-ballplayer. Taylor follows with his own story about seeds his father planted. He's old enough to remember the end of Dale's career: the father-son games when they wore matching uniforms and spent long hours in the clubhouse. "Growing up, I thought my dad was cool," he says. "Also, and this is a religious part, but as someone who is LDS, sometimes you feel like, Will people think I'm weird because I'm Mormon? And then I would go in there and everyone loved my dad. Everyone was his best friend. That's what I always tell people. If I can be halfway like that ..."

Dale looks like he might cry.

I wish I could disappear and let this family have its moment, but I'm also glad to witness the rarest thing in the world: a man content with his choices. Baseball was most valuable to him because it gave him the freedom to be completely present as his children grew up, which led him here. All any of us can hope for is to love and be loved like this. Dale covers his eyes for a moment.

"Thank you," he says to his son.

The conversation moves on, but Dale is still running Taylor's compliment over in his mind. He rubs his son's shoulder and again whispers "Thank you," as his voice lowers and he is overcome with his blessings.