How Hong Kong government helped put independence activist Andy Chan back in the spotlight

Before co-founding Hong Kong National Party in 2016, Chan’s first taste of protest came during Occupy campaign in 2014

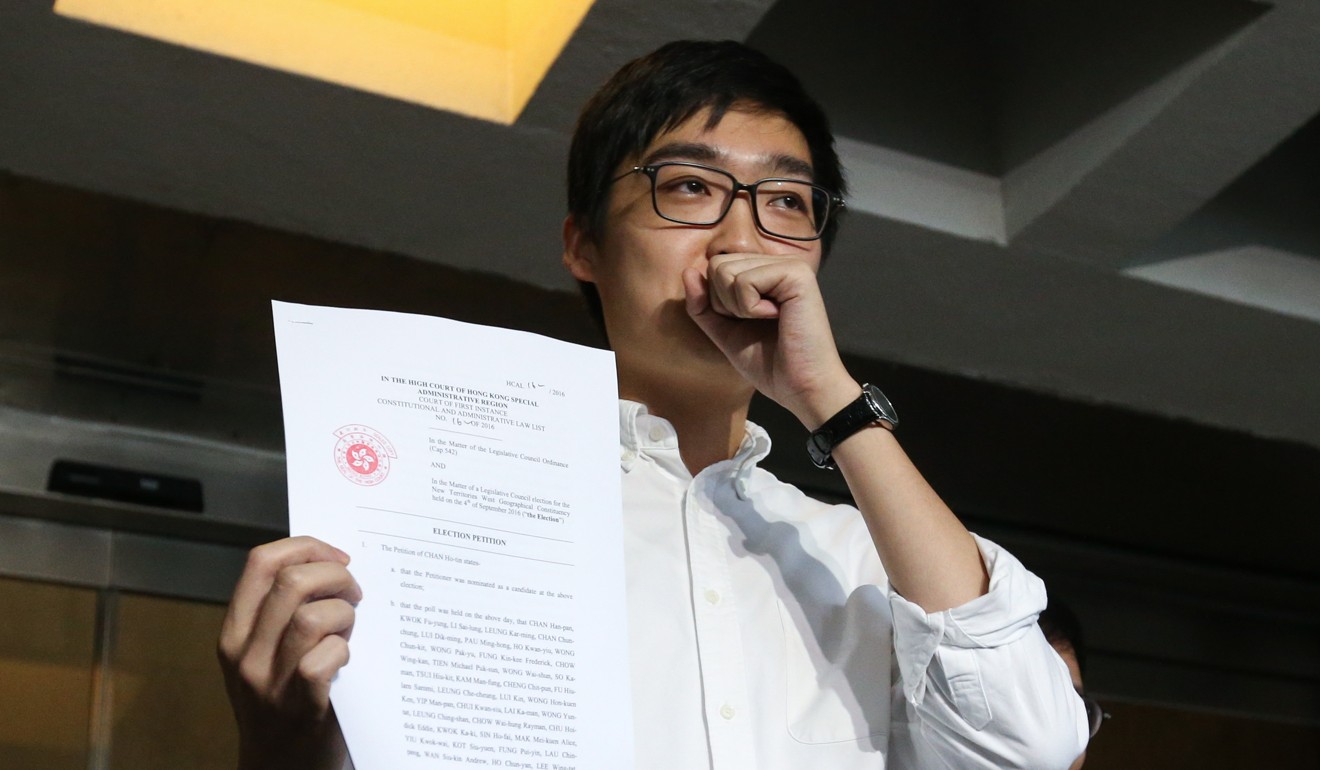

Andy Chan Ho-tin has found an unwitting ally in his efforts to keep the faltering Hong Kong independence movement in the spotlight – the city’s government.

A relative newcomer to the scene, Chan’s Hong Kong National Party is facing the likelihood of becoming the first political group to be banned by the government since the city’s return from British to Chinese rule in 1997.

The government’s move puts Chan and his small band of followers – and calls for independence from China – firmly back in the political spotlight after fading away in recent months.

So just what has Chan been up to and what may have prompted the authorities to act?

Chan, born in Hong Kong in 1990, has been involved in social activism for less than four years and said in an interview in 2016 that he used to be a “keyboard warrior” – someone who conceals his true identity but vents his anger in aggressive posts online.

Shortly before graduating from Polytechnic University with a double degree in marketing and industrial and systems engineering, Chan spearheaded his first campaign in 2015. It called for the PolyU student union to split from the Hong Kong Federation of Students, an alliance that was criticised by young people for not being “progressive and well managed enough” after it took a leading role in Occupy.

Hong Kong separatist party faces unprecedented government ban

Chan’s first attempt at activism succeeded in April that year, as 1,700 PolyU students voted in a referendum triggered by his campaign, including 1,190 who were for dissociation and 403 against.

After graduation, Chan reportedly worked for an engineering firm, but little is known about what he currently does for a living.

At that time, Chan said the party would use “whatever effective means” available to push for independence from China, including fielding candidates in the Legislative Council election in September that year and coordinating with other pro-independence localist groups both locally and abroad.

“Regarding the use of violence, we would support it if it was effective in making us heard,” Chan said at a press conference he conducted alone.

Pro-independence party crackdown ‘raises alarm bells’ for Hong Kong

But Chan was unfazed by the criticism. Asked in April that year if he would consider organising an armed revolution to achieve the party’s goals, he said that while there was no need to do so at that time, he would not rule out such a possibility in the future.

In May 2016, the party set up street booths with about 30 supporters to promote its political ideas.

Two months later, in July, Chan announced his bid to run in the Legco election in September that year. The announcement came just as the government introduced a new form in which election candidates had to declare they would uphold the Basic Law, which states that the city is an “inalienable part” of China.

Chan and several other pro-independence candidates did not sign the declaration form, and were banned from running in the election.

Britain calls for respect of Hong Kong freedoms as party faces shutdown

In August 2016, Chan and four other independence advocates banned from the election defiantly vowed at a rally that they would press on with their cause and campaign for wider public support. He claimed that more than 10,000 people attended the protest, but police said the turnout peaked at 2,800. Chan also said at the rally that his ultimate aim was to have his camp govern Hong Kong.

A month later, as the new school year started, Chan distributed pamphlets and stickers promoting Hong Kong independence outside several secondary schools.

He also claimed at the time that more than 100 young people had joined the party’s “secondary school pupil political enlightenment programme”.

Chan also took part in numerous political meetings abroad.

In November 2016, Chan met Mongolian exiles at the inaugural meeting of the Southern Mongolia Congress, in Tokyo. The act was strongly criticised by pro-Beijing politicians in Hong Kong, as the activists supported the independence of parts of Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang from China.

A month later, Chan was among a group of activists who spoke at a press conference in Taiwan on the topic of “prosecutions of human rights and self-determination in Asia”.

Hong Kong localists now spout extreme nonsense

Locally, Chan tried to bid to operate stalls at the city’s largest Lunar New Year fair in February last year, but was barred by the government due to public order and safety concerns.

This month he attended another press conference in Taiwan, organised by the International Monitor of Hong Kong Civil and Political Rights.

The bureau and police have declined to disclose the case’s details.