A handful of youthful poems by Daphne du Maurier have been found in an archive of letters, with two previously unknown discovered hidden behind a photograph frame.

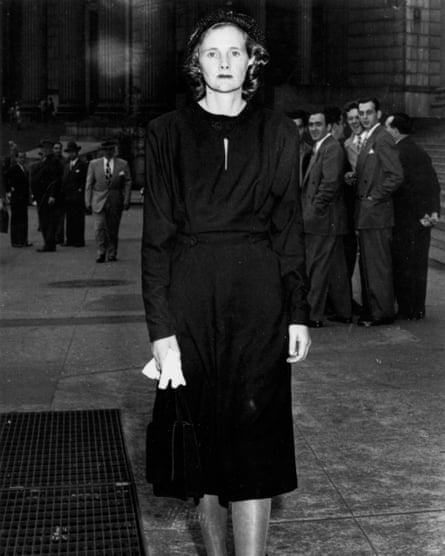

The two unknown poems were found tucked underneath a photo of a young Du Maurier in a swimming costume standing on rocks, which was part of an archive of more than 40 years of correspondence between the author and her close friend Maureen Baker-Munton, now put up for auction by Baker-Munton’s son Kristen.

Auctioneer Roddy Lloyd was cataloguing the archive when he looked more closely at the photograph. “We were going through the last box of documents on my kitchen table, when for some reason I decided to take the picture out to have a better look. When I took it out of the frame, out popped these poems,” said Lloyd. “It looks like they’re from around the 1920s.”

In one of the poems, titled Song of the Happy Prostitute, Du Maurier writes: “Why do they picture me as tired and old ... selling myself with sorrow, just to gain a few dull pence to shield me from the rain.” On the other side of the sheet of paper hidden behind the photograph, she writes in an untitled poem of how:

“When I was ten, I thought the greatest bliss / Would be to rest all day upon hot sand under a burning sun .. / Time has slipped by, and finally I’ve known / The lure of beaches under exotic skies / And find my dreams to be misguided lies / For God! how dull it is to rest alone.”

Lloyd said he believed they were written by Du Maurier when she was in her 20s. “The poems are not juvenile ones of a child, nor the polished products of her later years,” he said. “They show her working on her craft at an interesting time and are perhaps from her early visits to Ferryside, at Bodinnick in Cornwall, where she would write. The Song of the Happy Prostitute is really interesting but not, perhaps, what one would expect from Du Maurier – which might explain why it was hidden away in this fashion, probably by Du Maurier herself. It was then given to her great friend Maureen.”

Along with the poems, the archive contains hundreds of letters, many of them giving an insight into the writer’s relationship with her husband, the Army general Sir Frederick Browning, including his affairs and his alcoholism. In 1957, she writes to Baker-Munton of her husband’s mistresses, “if they see I am determined to stick by Moper [her pet name for Browning] in London or in Timbucktoo [sic] and not leave him, the desire may go out of the game”. In 1959, she writes of how “I couldn’t care less if he buggered his batman in the first world war … we’ve just got to clear it up once and for ever”.

And two years later, she writes of her disillusionment over his drinking over Christmas, “sneaking to the car and drinking half a bottle of whiskey sort of thing”. “Maureen, I could have wept with disillusion,” she wrote. “It just ruined my Christmas, with him all squiffy and with that wild look in the eye ... So you can imagine I was damn glad when Christmas was over, but then had to face Moper’s continued whisky swilling.”

In 1966, a year after Browning’s death, her letters show her still coming to terms with her loss: “I think much younger men and women would get over it quicker, but not after 33 years together. I put fresh rhodies in Moper’s room, and I always feel in a happy way that he is around, almost as if he were saying cheerfully, ‘Good Lord, duck, I’ve been dead a year’ and carrying on with some routy business.”

The archive also contains letters touching on Du Maurier’s relationships with Ellen Doubleday, the wife of her American publisher and with whom the author fell in unrequited love, as well as Gertrude Lawrence, with whom she had an affair. Of Lawrence, she writes to her friend: “Gertrude is not costing quite so much in flowers, because I am sending up daffs and rhodies – also eges, sometimes! It all pays, as I get cooing telephone calls! and the theatre is packed all the time, as she won’t want to chuck it up and go back to the US yet awhile.” Lawrence was acting in Du Maurier’s play, September Tide, playing the part of Stella, who was originally based on Doubleday.

The lot of letters will be sold by Rowley’s of Ely on 27 April.