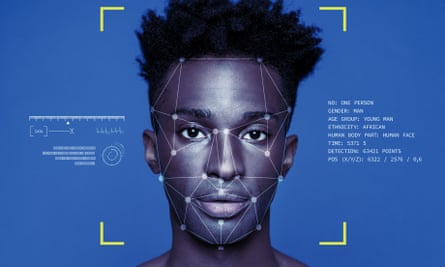

Last week, all of us who live in the UK, and all who visit us, discovered that our faces were being scanned secretly by private companies and have been for some time. We don’t know what these companies are doing with our faces or how long they’ve been doing it because they refused to share this with the Financial Times, which reported on Monday that facial recognition technology is being used in King’s Cross and may be deployed in Canary Wharf, two areas that cover more than 160 acres of London.

We are just as ignorant about what has been happening to our faces when they’re scanned by the property developers, shopping centres, museums, conference centres and casinos that have also been secretly using facial recognition technology on us, according to the civil liberties group Big Brother Watch.

But we can take a good guess. They may be matching us against police watchlists, maintaining their own watchlists or sharing their watchlists with the police, other companies and other governments. Our faces may even be used to train the machine-learning algorithms deployed by oppressive regimes such as China, which uses facial recognition technology to monitor and control its people, particularly its Uighur Muslims, more than a million of whom are interned in concentration camps.

Sounds far-fetched? If only. This year the FT also reported that Microsoft built a training dataset of 10m faces taken from 100,000 people and shared it with military researchers and Chinese companies, while NBC News reported that IBM had taken millions of online photos from Flickr, a photo-sharing app, and used them to train facial recognition software. The training datasets Microsoft and IBM created were shared widely, even though neither obtained people’s consent before taking their faces – a common practice that Prof Jason Schultz, of the New York University School of Law, has called “the dirty little secret of AI training sets”.

A British company called Facewatch has been using its facial recognition software to match people against police watchlists – and against watchlists compiled by its customers. In February, it was reported that Facewatch was “on the verge of signing data-sharing deals with the Metropolitan police and the City of London police”, was “in talks with Hampshire and Sussex police”, and was testing its software in “a major UK supermarket chain, major events venues and even a prison”. The software, which was trained on the faces of people without their knowledge or consent, has already been deployed in football stadiums, shopping centres and gyms in Brazil.

With more than 6m CCTV cameras in the UK, and 420,000 in London, we are primed to think that facial recognition technology is like CCTV and any concerns are soothed by arguing that “if we have nothing to hide, we nothing to fear” and that it’s worth sacrificing privacy and civil liberties if it helps to catch criminals. This misses the dangers that this technology poses. It does not work as well on people with darker skins, women and children – well over half the population – who are at risk of being misidentified and having to prove their innocence. This violates a core tenet of living in a liberal democracy – that we are innocent until proved guilty.

Even if it worked to a high degree of accuracy (it will never be 100%), it still transforms us all into possible suspects, whose innocence must be proved by continuously checking us against watchlists. It risks a chilling effect on our rights to assemble and to free speech, because people may not want to exercise these rights if it means they will end up on a watchlist. Our biometrics can be stolen, as the Guardian reported last week, but we cannot reset our face the way we can reset our usernames and passwords. It makes us vulnerable to tyrants, for whom a technology that tracks us without our knowledge offers new possibilities to persecute according to our ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality, immigration status or political beliefs.

Even as facial recognition technology metastasises in the UK, it’s unclear whether it’s legal. The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, doesn’t know, which is why he wrote to Argent, the consortium that, at King’s Cross, is taking our faces without our knowledge or consent, to ask it what it thinks. The information commissioner, Elizabeth Denham, doesn’t know, which is why she launched an investigation into Argent’s use of facial recognition. She has not yet indicated whether she will widen the scope of her investigation to include all of the other companies and organisations found by Big Brother Watch to be using the technology too.

The police don’t know, but they’re about to find out. Denham is also investigating the police use of facial recognition technology; and the human rights organisation Liberty took legal action against South Wales Police – the verdict is due imminently. The odds don’t look good: researchers at the University of Essex warned in May that the use of facial recognition by the London Metropolitan Police would be unlikely to withstand a legal challenge.

What we do know is that our face is not protected under British law, unlike other biometrics such as DNA and fingerprints. That is because the government has failed since 2012 to pass legislation updating our biometrics protections. Its efforts have been so dismal that all three data regulators (the surveillance camera commissioner, the biometrics commissioner and the information commissioner) have said that the government’s biometrics strategy is “not fit for purpose and needs to be done again”, while the science and technology committee in the House of Commons has called for a moratorium on the use of facial recognition technology.

Now that the UK’s “dirty little secret” has been revealed for all the world to see, the government has run out of excuses. Parliament must protect all our biometrics in law immediately, so that Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four can be fiction of our lives, not a fact.

Dr Stephanie Hare’s book on technology ethics will be published later this year