Movie-Prop Cash Is Fooling Cashiers

The strange psychology of why so many people fail to notice obviously counterfeit money

The Joker torching a mountain of cash in The Dark Knight. Walter White toting around his 55-gallon-drum nest eggs on Breaking Bad. The bags of $100 bills that Jason Bateman’s character launders on Ozark. Each scene was shot with prop money—phony bills that look real on-screen, but up close have certain glaringly obvious tweaks. Where an authentic $100 bill says “The United States of America,” prop money usually has this caveat: “For Motion Picture Use Only.” Look even closer, and Ben Franklin might be smirking.

This kind of nonlegal tender is regulated by federal law and, until recently, was controlled by Hollywood prop houses and closely monitored by the Secret Service. But in the past few years, thanks to new technology, the cost of making fake money has plummeted. Shady merchants have in turn begun selling what they describe as “prop money”—but with little regard for the laws and customs governing movie money.

According to police officials I spoke with, cheap counterfeit bills began proliferating on Amazon and eBay around 2015. Today, one can easily order 100 C-notes for $10. In a story published in the Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Argus Leader in March, a local Secret Service agent, Randy Walker, said prop money is the most popular type of counterfeit bill currently in circulation. “People don’t have to make anything,” he explained.

As the Secret Service has struggled to keep up, other types of fake money with ostensibly legitimate purposes have also popped up online—such as Chinese-made “training money,” designed for bank tellers. In lieu of a “For Motion Picture Use Only” disclaimer, these bills are stamped with pink characters that translate to “Bill to Be Used for Counting Practice.” Russian-made bills are harder to spot; serial-number fields are filled with a mix of numbers and Cyrillic characters (translation: “Souvenir”), while on a $20 note, the image of the White House is relabeled “Donetsk City,” the name of a shopping mall in Ukraine.

Sometimes the cheap money works: The police department in Grants Pass, Oregon, recently received reports of “movie money” being successfully passed at local businesses. Sometimes it doesn’t: Last year, employees of a Safeway in Washington State called the police when a woman allegedly tried to buy a $5,000 Visa card with a fistful of prop money. And sometimes people get killed: In 2017, a Georgia man was fatally shot during an alleged drug buy involving seven kilos of cocaine and $230,000 in prop cash. A Texas teen died under similar circumstances last year in a bungled $200 pot deal.

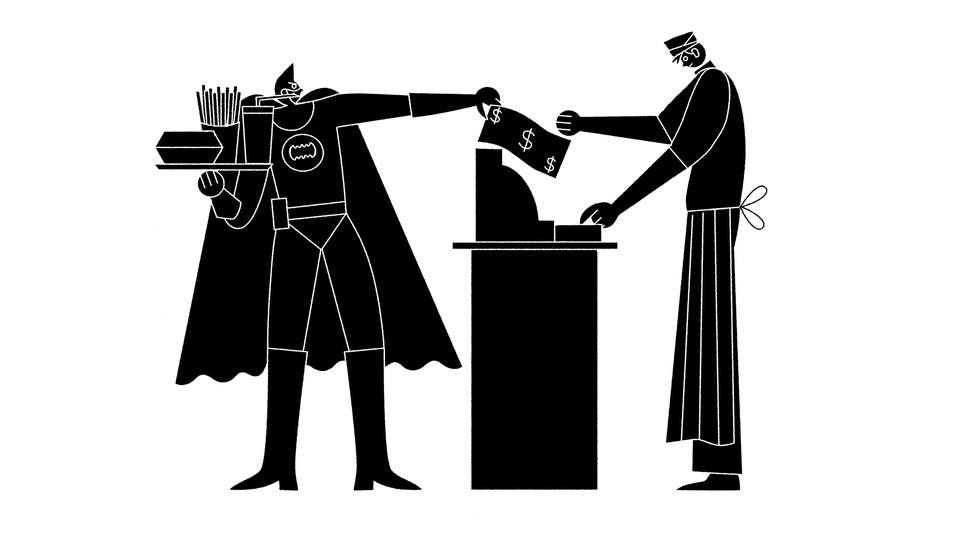

Tip: If you’re going to pay with prop money, you’re probably better off trying to score hamburgers than drugs. Criminals seeking to pass low-quality bills seem to do best targeting businesses where cashiers are bored and customers impatient, such as fast-food restaurants and gas stations. Other tricks include crumpling bills (to disguise the cheap paper stock) and spraying them with starch (which helps evade detection by an iodine pen).

Rich Rappaport, the owner of RJR Props, has supplied millions in prop money to film projects including Baby Driver and The Wolf of Wall Street. (One type is for “fanning, flashing, raining, counting”; a more expensive variety is for close-ups.) “If I broke the law, I could make [the money] much more realistic, but I simply won’t,” Rappaport told me, lamenting that other prop money has gotten too close to the real thing. People “cross the line, and then the money gets used in a felony crime.”

But even if mail-order money is getting better, much of it is still conspicuously fake. The Chinese bills, after all, have pink Chinese characters stamped across them—wouldn’t an average person notice?

Maybe, maybe not. A 1979 study titled “Long-Term Memory for a Common Object” tried to determine how accurately people recall a penny. On each of five tests, which included drawing a penny and finding an illustration of a real one in a group of fakes, subjects performed poorly. “I would guess the same thing is happening with prop money,” says Daniel Schacter, a psychology professor at Harvard. “We generally do not need to remember all the specific visual details that make up bills or coins. So we have poor memory for those details.”

If we’re paying attention to details at all, that is. Carl Bombara, a rare-currency dealer in New York City, says that under most circumstances, we assume money is genuine. “People don’t look at dollar bills,” he told me. “If you give the cashier at Walmart a $3 bill, they’ll give you change.”

This article appears in the June 2019 print edition with the headline “Really Fake Money.”