The Doorbell Company That’s Selling Fear

An Amazon-owned firm is hiring editors to push local crime news to its users.

When news organizations think about competition from tech companies, it’s usually in terms of the audience’s attention and advertisers’ dollars. But if Amazon has its way, a new sort of competition may be coming from a mixture of surveillance, fear, and doorbells.

Amazon is currently looking to hire someone with the title “Managing Editor, News.” But it’s not for the entire Amazon empire—it’s for the small slice of it that makes security-focused doorbells, Ring. (Amazon bought Ring last year for more than $1 billion.)

Here’s the job description:

The Managing Editor, News will work on an exciting new opportunity within Ring to manage a team of news editors who deliver breaking crime news alerts to our neighbors. This position is best suited for a candidate with experience and passion for journalism, crime reporting, and people management. Having a knack for engaging storytelling that packs a punch and a strong nose for useful content are core skills that are essential to the success of this role. The candidate should be eager to join a dynamic, new media news team that is rapidly evolving and growing week by week.

The job requires at least five years’ experience “in breaking news, crime reporting, and/or editorial operations” and three years in management. Preferred traits include “deep and nuanced knowledge of American crime trends,” “strong news judgment that allows for quick decisions in a breaking news environment,” and experience using “social media channels to gather breaking news.”

That’s right: A doorbell company wants to report crime news. It already is, actually. Several people on LinkedIn describe their jobs as “news editors” at Ring.

I hope a really thoughtful person gets that job, but I’m going to go out on a limb and say that this is a really bad idea.

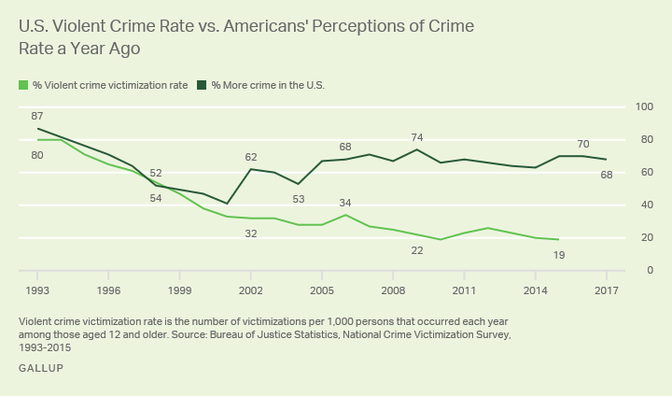

Crime has declined enormously over the past 25 years, but people’s perception of how much crime there is has not. A majority of Americans have said that crime is increasing in each of the past 16 years—despite crime in each major category being significantly lower today than it used to be.

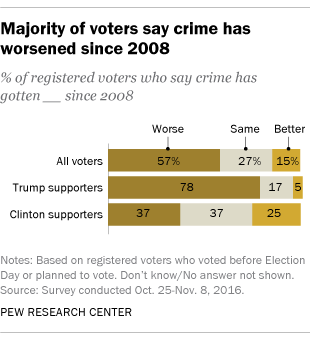

A 2016 Pew survey found that only 15 percent of Americans believed (correctly) that crime was lower in 2016 than it had been in 2008—versus 57 percent who thought it had gotten worse. (Those inaccurate beliefs are not evenly distributed politically, with conservatives, Republicans, and Trump supporters each more likely to see dangers the statistics don’t support. A couple of hours spent watching Fox News makes the approach pretty clear.)

Gallup data show that a majority of Americans have only said that crime was getting better in their community once in the past 47 years—October 2001, when presumably they had other concerns to focus on.

These mistaken beliefs are driven largely by the editorial decisions of local media—especially local TV newscasts, which are just as bloody today as they were when murder rates were twice as high. There’s a term for it: “mean world syndrome,” the phenomenon where media consumption makes people see the world as more violent and dangerous than it really is. And TV has historically been the worst offender; a body of past research has shown that people who rely on local TV most for their local news are more fearful of crime; that local TV’s crime news disproportionately shows black criminals and increases racial fears; and that the more local TV news you watch, the more fearful you get.

Those fears and mistaken beliefs are important: Consuming more local TV crime news is associated with supporting more punitive anti-crime measures, and reducing exposure to crime news can even increase presidential approval ratings.

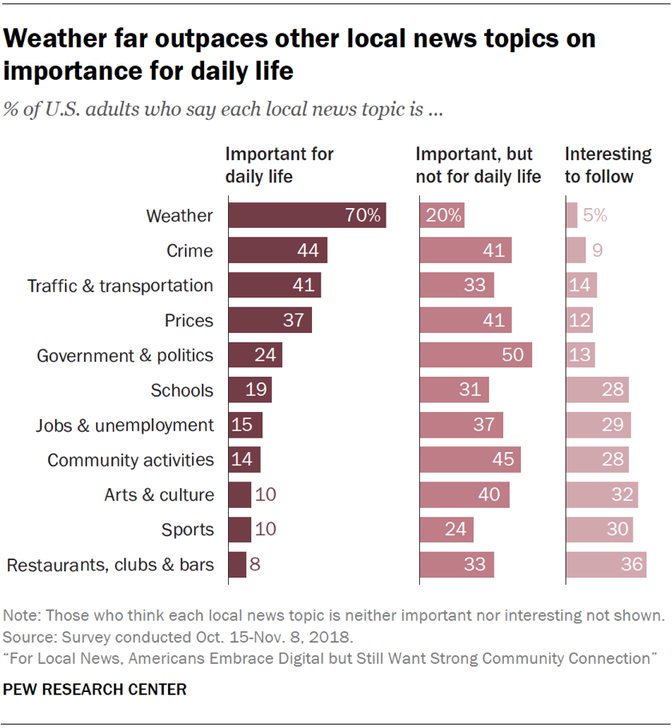

A report from Pew last month asked people about various topics in local news and asked both whether they thought they were important or interesting and, if so, why. Did they consume news about a topic because it was important to their daily lives; because it was important, but not to their daily lives; or just because they found it interesting?

Those surveyed overwhelmingly said crime news was important. But more striking is that so many of them said it was important to their daily lives. To put that in context, the top three “important to their daily lives” topics were weather, crime, and traffic. Weather and traffic really are important to your daily life! Figuring out what to wear or which route to take to work are very useful services that local news can provide. But local TV news has convinced Americans that stories of violence are news-you-can-use at the same sort of level. (Only 9 percent said they followed local crime news because it was “interesting.”)

In recent years, a number of newspapers have decreased the emphasis they put on crime stories in their coverage. There are a number of reasons for this shift. TV is always going to have an advantage when covering day-to-day crime. There are fewer reporters to go around than there used to be. And as newspapers have retooled for digital subscriptions over page views, crime news is less important to what they’re offering readers.

(When I worked at The Dallas Morning News in the 2000s, a consultant once came through telling editors that crime news was what the audience really wanted on the web, and the paper changed its presentation accordingly to chase page views. For a while, the homepage of DallasNews.com was almost as bloody as the 10 o’clock news. But looking at the homepage as I write this—with the paper having pivoted to seeking digital subscriptions—only three of the top 17 stories are about violent crime.)

In an American Press Institute study asking new newspaper subscribers what topics they were most interested in, “crime and public safety” ranked only seventh out of 19; only 18 percent of respondents included crime news in the three topics they followed most. Meanwhile, local TV news stations, fighting for ratings in an environment of declining attention, have mostly stuck to their guns, so to speak, keeping crime news prominent.

In other words, news organizations—for better and for worse—respond to audience incentives. If they think their audiences want more crime news, they’ll probably produce more of it—and vice versa.

But news organizations have multiple and sometimes conflicting incentives that might affect how they present the local police blotter. A company that sells security-optimized doorbells has only one incentive: emphasizing that the world is a scary place, and you need to buy our products to protect you.

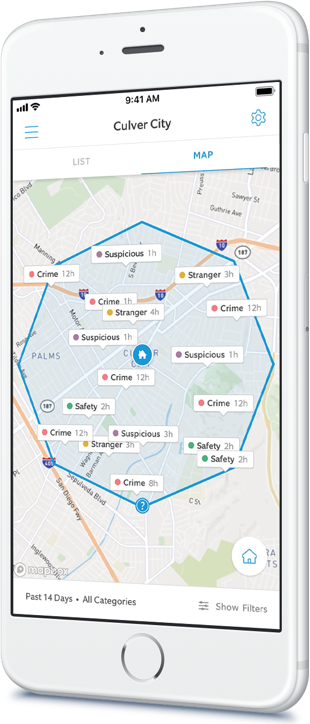

Ring already has an app called Neighbors that, judging by its marketing, encourages people living in bucolic suburbs with wrought iron gates to feel as if they’re in the last un-zombified neighborhood in The Walking Dead (I assume this app is where this new managing editor’s work product will be found):

The Neighbors App is the new neighborhood watch that brings your community together to help create safer neighborhoods. With real-time crime and safety alerts from your neighbors, law enforcement and the Ring team, the Neighbors App proactively keeps you in the know. Criminals target neighborhoods, not individual homes. But with real-time crime and safety alerts from your neighbors, you’ll stay one step ahead of crime.

Basically, it’s an app that makes you want to see your neighborhood the same way that this screenshot does: Suspicious Stranger Crime Crime Stranger Crime Suspicious Suspicious Crime Crime Crime Crime Suspicious Stranger Crime.

So think about this managing-editor job. Ring wants to be “covering local crime” everywhere, down to the house and neighborhood level. So one managing editor, plus however many other people are on this team, is supposed to be creating a thoughtful, nonexploitative editorial product that is sending journalistically sound “breaking news crime alerts,” in real time, all across the country. Are they really delivering news or just regular pulses of fear in push-notification form? If that’s the job, it is literally impossible to do responsibly.

I downloaded Neighbors—you can do so without owning a Ring doorbell—and plugged in my address in boring Arlington, Massachusetts, a city of 45,000 that recorded zero murders and only seven robberies last year. It decided I needed to know that someone in the uniform of a local lawn-care service had recently knocked on someone’s door instead of using the doorbell and, when no one answered, left. Also, there was a building fire two towns away, a couple of days ago.

Also, two young people, one male, one female, wearing identical T-shirts and lanyards with name badges, carrying clipboards—likely trying to get signatures for some cause or another—rang a doorbell and then walked away when no one answered. “Anyone know who they are?” the post from a Neighbors user asked, perhaps concerned about Islamic State infiltration of the Boston suburbs. “Call the police,” one helpful commenter replied. (It doesn’t take a critical race theorist to suspect that that suggestion might turn into action for people of color who dare to approach a front door.)

Now, plenty of other apps aim to turn the magical stew of unverified reports, stand-your-ground ideology, and paranoia into dollars. Citizen—an app that used to have the more-straightforward name, Vigilante—is perhaps the most well known.

But what bugs me about Ring’s approach is that it wants to bring in the credibility of journalism as a layer on top of the state of constant fear it promotes. A company that relies on people feeling unsafe to sell its products will now be able to take whatever trust professional journalism has left and put it to work toward that end. It’s like relying on the people who make antivirus software to tell you about the latest cybersecurity issues: Even when the reporting is sound, it’s still prone to exaggerating the scale of the threat and still aimed at making you so afraid that you give them money.

(A cynic—okay, me—might note that this managing-editor job is listed under “Marketing & PR,” not editorial.)

Is it possible that real journalists can make the product better and less paranoid? Sure, it’s possible. But the reality is that “breaking crime news alerts” are not something the majority of people needs—especially if “two Greenpeace volunteers stood on my porch for 30 seconds” is the bar we’re talking about. It’s not actionable intelligence—it’s puffing a little more air into an atmosphere of fear.

News organizations’ coverage of crime is flawed in a million different ways. But at least they’re operating in a context where crime is one story out of dozens and where not all incentives point in the same direction. Even once you get past the absurdity of it all—a doorbell company writing crime news—it’s a bad direction to be going in. It says it’s selling safety, but it’s really selling fear. And it’s also a reminder that, if local news organizations go away, you might not like what fills the gaps they leave behind.

This post appears courtesy of Nieman Lab.