Trending

Co-working goes corporate

As the flexible office industry sees explosive growth in New York and beyond, it’s increasingly ditching the freelancer market and targeting blue-chip clients at a rapid rate

The 11-story Beaux-Arts building at 88 University Place in Greenwich Village is the kind of property every co-working company dreams of occupying.

Sitting just south of Union Square and partly owned by fashion designer Elie Tahari and WeWork co-founder Adam Neumann, it has small floor plates that can be easily turned into cozy, communal work stations, and the nearby NYU campus promises a steady supply of young, well-heeled freelancers and aspiring entrepreneurs.

In late 2015, WeWork signed a lease for eight floors, totaling 70,000 square feet, at the building, with plans to convert it into a huge co-working hub. But it didn’t turn out that way.

By 2017 the flexible office industry had changed, and so had WeWork’s plans for the building. That April, news broke that 88 University would not house freelance graphic designers and other creative types in the East Village. Instead, computing giant IBM agreed to take over the entire property as a temporary New York office while it searched for a more permanent space.

WeWork — which is now Manhattan’s largest office tenant and occupies more than 7 million square feet throughout New York City — would still furnish the building, staff the reception desk and keep the coffee and beer flowing.

But for all intents and purposes, the property became an IBM corporate office.

“Real estate’s not IBM’s core business,” said Glenn Brill, a managing director at FTI Consulting, which advises co-working companies and landlords. “The less time they spend on it, the better.”

Related: The co-working space race

The booming co-working industry, which has grown its footprint in New York City by 600 percent since 2009, isn’t what it used to be.

Marketing materials often depict groups of young, attractive colleagues bonding in shared office spaces, sitting on couches with laptops and working in between pingpong matches.

But in reality, co-working — or at least that version of it — is no longer driving the bottom lines of flexible office providers. The rapid growth of firms such as WeWork, IWG, Industrious and Knotel now has almost everything to do with serving the basic office needs of established corporations like IBM and UBS. And what’s been branded as a revolutionary answer to office life in the 21st century now more closely resembles a business model that’s been around for decades: commercial property management.

While shared office space for freelancers still exists of course, industry leaders say it’s a shrinking portion of the business.

“Co-working doesn’t work,” said Marcus Moufarrige, COO of the Australian company Servcorp, which has offered flexible space services since the late 1970s. “The latest iteration of it is not that new; it was around pretty extensively during the dot-com boom. And it didn’t work then, either.”

A different tune

While some potential co-working users are still being sold on the entrepreneurial community and the freelancer economy, investors and landlords are increasingly hearing a very different proposition.

In 2012, Jamie Hodari, a former hedge funder who had just launched the co-working startup Industrious, dialed into an investor call with a group of podiatrists in Michigan who wanted a piece of the action.

The co-working concept — which started more than a decade ago with the aim of bringing lone Silicon Valley hopefuls together under one roof — had become an international phenomenon with more than 2,000 locations worldwide. Hodari was selling the latest way to curate shared space for budding entrepreneurs.

But a year later, Hodari’s pitch to another group of investors had changed: Industrious wanted to target more than just graphic designers and app developers. It would also go after traditional office tenants with short-term leasing needs — a large market that was neither new nor deserving of a neologism.

“We had a very boring observation: This is an outsourcing industry,” Hodari told The Real Deal in a recent interview.

In the five years since, the top co-working companies have made the same observation. Rather than catering to individual freelancers and small early-stage startups, the industry is increasingly targeting much larger tenants.

Companies of at least 1,000 employees, which WeWork calls its “enterprise clients,” now make up a quarter of its memberships and revenue. Knotel, which never tried the individual-member model, claims companies with multiple offices and more than 100 employees account for 95 percent of its customers.

Manhattan’s top commercial brokerages — some of which now compete with co-working companies in office services — are acutely aware of the shift. News broke late last month that CBRE is launching its own flexible office management arm, called Hana. That business will compete with WeWork, Knotel and others for partnerships with landlords.

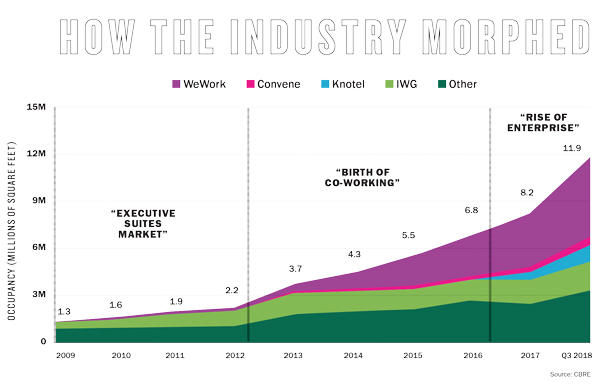

CBRE closely tracks the industry and divided its rapid growth into three distinct phases, starting with the “executive suites market,” which predates 2009, the “birth of co-working,” which took off in 2012, and the “rise of enterprise,” which began in 2016.

Today, the biggest co-working companies vie for partnerships with landlords to manage space for blue-chip clients, while offering everything from coffee and beer to facilities maintenance and IT. Some are also expanding into brokerage, interior design and data services in pursuit of additional revenue, creating a new wave of competition for companies that specialize in those fields.

What the co-working industry has retained from its early days is its aesthetic sensibility — creative office layouts and post-industrial chic.

Insiders see the expanding business as a way to change the entire commercial real estate industry by making leases more flexible and adding more amenities to office buildings. “The change is they’re taking this idea of flexibility and pitching corporate America,” said FTI’s Brill.

“Long live co-working”

As the industry continues its shift, a handful of property owners are even launching their own hip co-working brands.

At Rockefeller Center, Tishman Speyer’s Studio — which gives its members access to Clubhouse by ZO, an exclusive lounge where they can rest in communal “nap pods” and attend meditation classes — is one example.

Thais Gallis, a senior director at the family-owned real estate firm, said one of the reasons behind launching Studio was the hope of creating an “entryway for new companies into our properties.”

Among the city’s office landlords, Tishman Speyer also has one of the highest concentrations of co-working tenants, including both WeWork and IWG, data from the commercial brokerage Avison Young shows. The firm’s two-pronged approach of bringing on co-working tenants and starting its own brand speaks to the rapidly growing demand for such services.

Scott Rechler’s RXR Realty, which has invested in several co-working funding rounds, is also getting into the members-only business. RXR recently announced an agreement with office amenities operator Convene to design and manage an exclusive penthouse club at its 75 Rockefeller Plaza office tower.

Other landlords are taking it a step further and teaming up with co-working companies on development projects.

Knotel partnered with Brooklyn-based EcoRise Development to build an office property in Gowanus that will allow Knotel to manage up to 300,000 square feet at the site, and WeWork joined Rudin Management and Boston Properties to build a 675,000-square-foot office project in the Brooklyn Navy Yard where it will occupy a third of the space.

Megan Spinos, director of strategy at the design firm Vocon, which creates social spaces for both co-working companies and large companies, described a major shift in the U.S. workforce that’s given the communal working trend legs.

“Where we used to be part of a Kiwanis Club, we don’t really do a lot of that anymore. And because we spend so much of our time forging ahead with work life, there are different ways that we’re trying to [create community] in the workplace,” she said. “Sometimes our work is really solitary and we’re looking to form relationships.”

Mark Gilbreath, who runs the online office listing platform LiquidSpace, said the promise of a shared workplace utopia with countless amenities is “intoxicating.” But as companies like WeWork hit the limits of demand from wide-eyed entrepreneurs, they’re catering to bigger firms at a fast-growing rate, he noted.

“Co-working is dead,” Gilbreath said. “Long live co-working.”

Pitching big business

WeWork’s deal with IBM was part of a broader push to distance the co-working giant from its original customer base.

Its Powered by We service line, which it launched in 2017, facilitates full offices and even corporate headquarters for major corporations. This past July, the company announced it would renovate and manage UBS’ 100,000-square-foot office in Weehawken, New Jersey.

The co-working giant is also zeroing in on midsized firms. This August, it launched HQ by WeWork, a service that allows midsized firms to rent out their own floors, implement their own designs and keep interactions with other companies to a minimum while still tapping into perks like regular cleaning and flexible lease terms.

WeWork’s chief growth officer, David Fano, acknowledged that it’s “difficult” to build a global flexible office brand by focusing only on small tenants. “There’s definitely a ceiling on the demand for that stuff,” he told TRD. “And as companies grow, unless you can serve the full life cycle of an organization, it’s inevitable they’re going to leave.”

Related: Who’s keeping it real

Fano insisted that WeWork never saw itself as just a service for freelancers and small-business owners, but said it underestimated the potential demand from larger clients in its early years.

“In the first half of [WeWork’s life], I don’t think we had such clarity on the enterprise potential,” he said.

Other flexible office providers like Industrious, Bond Collective and IWG also say bigger companies make up the bulk of their revenues. Industrious’ rapid shift from freelancer hubs to Fortune 500 office suites was prompted by an unexpected demand from a single customer.

In 2012, as Hodari made his first rounds of investor calls, his company provided a small space for then-two-year-old social media startup Pinterest. A year later, Pinterest expanded. And then it expanded again. Soon enough it had ballooned to the point that its executives said they needed a proper headquarters.

WeWork is moving its corporate headquarters (pictured) from Chelsea to the landmarked Lord & Taylor building on Fifth Avenue.

Today, Pinterest is valued at $12 billion and occupies 100,000 square feet at 651 Brannan Street in San Francisco. “They said, ‘We actually will get a better outcome if you do this,’” Hodari recalled, after Pinterest executives asked his company to manage the new headquarters.

The Pinterest deal made him rethink Industrious’ business model, and the firm’s marketing materials dropped any reference to freelancers and pivoted toward medium to large companies.

“That’s where the dogfight is right now — pitching to Johnson & Johnson, Exxon, Airbnb, Spotify that you are better than anyone else at providing a workspace their employees will be happy with,” Hodari said.

Industrious now has partnerships with General Motors, Lyft, Pandora, Freddie Mac and Chipotle. “We started to shift the balance of our customer set quite quickly,” Hodari added.

The freelance spillover

Knotel, one of WeWork’s biggest and youngest competitors, rejected the co-working label from the start.

Its CEO, Amol Sarva, who co-founded Knotel in 2016, said it’s not just that co-working companies underestimated demand from big firms — they also overestimated demand from small ones.

“A really superficial analysis of the labor market would be ‘Oh, half the market is freelancers’,” he said, pointing to statistics on how many people file tax returns as freelancers and contractors. “But do freelancers work alone? Do freelancers have their own offices?”

Most who do use offices work for larger companies and are often embedded in their spaces on a part-time basis, Sarva said. The industry shift was inevitable, he argued, but it’s having a spillover effect.

“This huge supply of freelancers who work in ever-shifting teams but together at companies — they need an office,” Sarva added.

The transition to bigger clients and a greater focus on property management impacts how firms like Industrious and WeWork design their spaces. “The large enterprise doesn’t want to live in a glass box side by side with a bunch of other startup companies with 47 square feet per person,” LiquidSpace’s Gilbreath said.

It’s not just about open floor plans, either, Vocon’s Spinos noted. “It really is a science based on how clients are going to use that space,” she said. “It’s not just open — it’s enclosed, it’s private, it’s semiprivate. It’s a bigger variety.”

Beth Moore, a managing director at CBRE who leads the brokerage’s flexible space business nationally, said major corporate clients are in the “dating” phase with co-working companies, trying out a variety of them for different office needs.

She said clients now expect much more than an edgy look or hip mission statement; when they tour new locations, they want to see a proven track record with larger companies.

“The worst-case scenario is you leave a space and say, ‘That was a cool furniture showroom,’” she said. “It’s not as easy as desks and comfy furniture and bad posture.”

“The worst-case scenario is you leave a space and say, ‘That was a cool furniture showroom,’” she said. “It’s not as easy as desks and comfy furniture and bad posture.”

“Asset-light”

As the co-working industry targets big corporate clients, the power dynamic with landlords is also changing.

Until last year, all but one of Industrious’ agreements with building owners were long-term leases that allowed it to sublet the space to other companies.

Behind the scenes, though, Hodari was pitching landlords to instead enter management contracts — revenue-sharing partnerships between the building owner and office operator.

While commercial leases often carry terms of 10 or more years, management deals allow third-party companies to occupy the space on a more flexible basis.

It took a while for landlords, who were cautious about doing away with long-term guarantees, to warm up to the idea, Hodari said. But the fact that they get a piece of the profits was a key selling point.

In the past 12 months, Industrious’ business model has flipped. Now, 75 percent of its new contracts are management agreements, which allow the firm to take on the office market’s version of a hotel franchise.

Knotel and Convene have also largely followed that model. And while WeWork still relies mostly on leases, the co-working giant has signed management agreements at a handful of locations.

In Silicon Valley’s venture capital circles, the shift into the management world — the so-called asset-light business model — is extremely popular.

Just as Uber refrains from buying its own cars and Airbnb typically refrains from buying homes, co-working companies are increasingly dodging the expensive liabilities that come with owning or leasing office space.

Silicon Valley-based Norwest Venture Partners led a $60 million funding round to Knotel last month, for instance, while the Los Angeles firm Fifth Wall Ventures led an $80 million funding round for Industrious in February.

“One of the most prevalent killers of companies is a mismatch in the duration of a company’s assets and liabilities — master leases are a long-term liability,” said Fifth Wall co-founder and managing partner Brendan Wallace.

Mindspace, an Israel-based flexible office startup that has 28 locations in Israel and Europe and recently expanded into the U.S., is also moving toward partnership agreements, said Itay Banayan, the company’s head of real estate. These deals make it “easier to weather the cycle,” he said, arguing that long-term lease obligations can become a burden to both co-working companies and landlords during a downturn.

Managing expectations

Landlords say their preferences are based on other factors, such as bank financing and prospective buyers.

Bob Savitt, founder of the New York-based office owner Savitt Partners, which operates a co-working spot at its 530 Seventh Avenue office building, said the decision between a long-term lease and a management deal largely boils down to a landlord’s investment strategy.

“If I want to sell a building, and I have a 10-year lease with a decent creditor and a security deposit, I can monetize that,” Savitt said. Long-term commitments can increase a building’s value in the eyes of potential buyers, he added, though “there’s not one preferred structure.”

Some landlords have taken to management agreements for the profit-sharing part of it, but many banks are hesitant to lend on buildings with such arrangements in place. Most traditional lenders still prefer the perceived stability of long-term leases, sources say.

At the same time, banks have greenlighted one of co-working’s riskier business practices. Many of WeWork’s leases have come without corporate credit guarantees, an extreme outlier in the generally conservative office leasing market, said Colliers International investment sales broker Yoron Cohen.

“It was a brilliant business plan,” Cohen said. “Landlords were happy to take [co-working companies] as long as the banks were willing to consider them as [creditworthy].”

He said what lenders see as WeWork’s “bankability” could lead to “spot spots” during a downturn — leaving landlords with co-working tenants that can’t pay rent.

“We all pray that it will end well,” Cohen added.

Inn, the future

While co-working is largely evolving from open floors to corporate suites, many in the industry say its next phase will be most akin to hotel flags.

A growing number of co-working companies will have their own distinct brands and different tiers of service similar to the budget, boutique and ultraluxury models that hospitality firms use. And as with big hotel corporations, it’s not inconceivable that a small number of firms could dominate the market.

WeWork’s executive hires in recent years show the industry is taking more than just a page from the hospitality sector. Michael Gross, its vice chair, used to run Morgans Hotel Group; Richard Gomel, its head of co-working, is a former Starwood Hotels & Resorts executive; and Pato Fuks, its regional manager for Latin America, founded the Argentinian hotel operator Fën Hoteles.

“WeWork is fundamentally trying to create a lifestyle brand,” said FTI’s Brill. “And that’s what hotels do to a large extent. That’s how they market themselves.”

In addition to its gym line and co-living division WeLive, the co-working giant now has half a dozen other lines of business including Off the Shelf, Powered by We and custom build outs.

IWG has also broadened its portfolio with Regus (its predecessor), Spaces, Number 18 and others. For most co-working firms in 2018, the goal is to capture all tiers of the office market — from ground-floor freelancer hubs to executive corner offices.

“Like within Hilton or Starwood, there are a lot of different brands,” CBRE’s Moore said. “We’re already seeing that take shape.”