One of the most significant fiction writers in English is retiring, to the greatest fanfare of his singular and titanically influential career. Alan Moore has promised that the (extremely late) final issue of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen will be his last comic, and his final contribution to an art form he utterly transformed, sometimes to his chagrin. His work in the 1980s on Miracleman, a deconstruction of the superhero myth, inspired so many imitators to darken formerly kid-friendly heroes that Moore has apologised more than once for it.

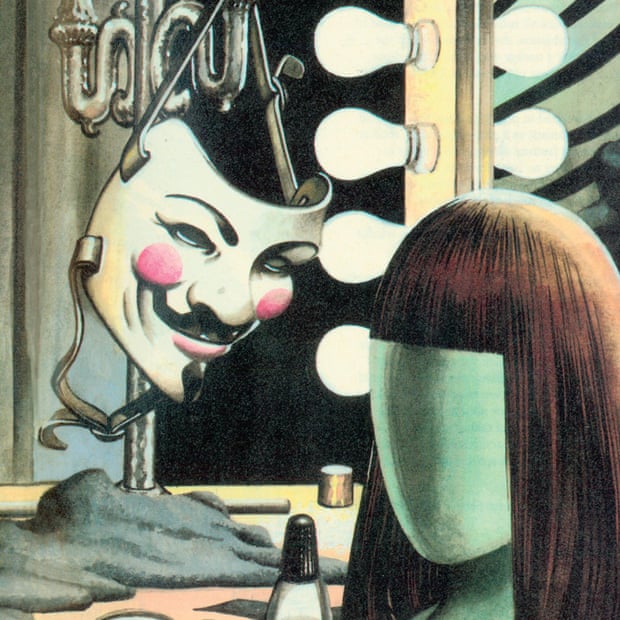

A brainy pop writer whose style veers between Stephen King and John le Carré, Moore’s influence can be felt everywhere – in our literature, on our screens, in our politics. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, quoted Watchmen’s Rorschach on Twitter, in response to reports that she was agitating the Democrats. (“I’m not locked up in here with YOU. You’re locked up in here with ME.”) Writers as diverse as China Miéville and Ta-Nehisi Coates have cited him as inspiration. HBO’s great post-Game of Thrones hope is yet another adaptation of Moore’s most popular book, Watchmen, which (co-authored with illustrator Dave Gibbons) has sold millions of copies since it was first published in 1987. He’s played himself on The Simpsons, seen his work adapted into a number of films – none very good – and even inspired an activist collective: the Anonymous group wear Guy Fawkes masks as a tribute to V, the anarchist hero of Moore’s and illustrator David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta.

Quick GuideThe five Alan Moore comics you must read

Show

V for Vendetta (1982 - 1989)

This dystopian graphic novel continues to be relevant even 30 years after it ended. With its warnings against fascism, white supremacy and the horrors of a police state, V for Vendetta follows one woman and a revolutionary anarchist on a campaign to challenge and change the world.

Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow (1986)

Moore's quintessential Superman story. Though it has not aged as well as some of his work, this comic is still one of the best Man of Steel stories ever written, and one of the most memorable comics in DC's canon.

A Small Killing (1991)

This introspective, stream-of-consciousness comic follows a successful ad man who begins to have a midlife crisis after realising the moral failings of his life and work.

Tom Strong (1999 - 2006)

A love letter to the silver age of comics that nods to Buck Rogers and other classics of pulp fiction. Tom Strong embodies all of the ideals Moore holds for what a superhero should be.

The League of Extraordinary Gentleman (1999-2019)

One of Moore's best known comic series, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the ultimate in crossover works, drawing on characters from all across the literary world who are on a mission to save it.

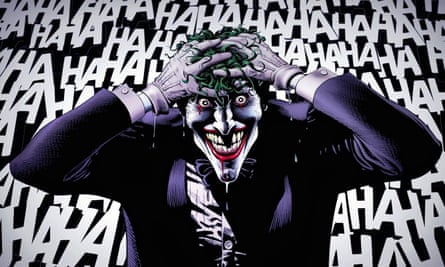

Moore draws very rarely: instead he writes comics scripts, and at punishing length. Those can run to hundreds of pages, describing every layer of background and every tertiary character. The scripts themselves, occasionally enclosed in deluxe editions of his work, are as detailed as David Foster Wallace novels. Describing Batman’s home city to artist Brian Bolland in the script for The Killing Joke, Moore wrote: “The lower and seedier levels of Gotham are more inclined towards a territory somewhere between David Lynch and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, all patches of rust and mould and hissing steam and damp, glistening alleyways. I imagine this strip as having an oppressively dark film noir feel to it, with a lot of unpleasantly tangible textures, such as you habitually render so delightfully, to give the whole thing a really intense feeling of palpable unease and craziness.” And Moore’s collaborators have always risen to his challenges, turning this overwriting into eye-popping set pieces.

Before Moore, and the likes of Frank Miller, Dave Sim and the Hernandez brothers, the idea that serialised comics could amount to literature was laughable, and that adults could enjoy them without irony creepy. But Moore has had a preternatural grasp of the intricacies of a genre – superheroes – widely considered to be devoid of them.

He asked troubling questions of superheroes, who had always appeared in stories that retroactively rewrote themselves and seemed to go on forever. Where was the end of these stories? Had we fully understood their beginnings? Was heroism even possible? The fates of silly costumed heroes became urgent in his hands: Krypto the Super-Dog, the shambling bog-monster Swamp Thing, a kid flying ace named Jetlad – each of these characters has moved me to tears.

Moore can be tiresome – his digressions into the minutiae of Kabbalah in his Wonder Woman-style fantasy comic Promethea are insufferable – but he could also be delightful. Top 10, his affectionate send-up of cop shows, was a riot of sight gags, rendered by artists Gene Ha and Zander Cannon. Parody and melodrama keep close company in his work, especially in what is arguably his masterpiece: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, created with the brilliant artist Kevin O’Neill. One character murders another with his magic penis at one point. It’s quite moving.

This lurid streak can make Moore a tough sell. One Swamp Thing features an issue-length sex scene in which one participant is a plant; yet the books’ central relationship hinges on the idea that Swamp Thing is the best man a woman could hope for, despite – or perhaps because of – his plant-ness.

Moore as the saviour of superheroes is ironic in many ways. For one, his work suggests that they are at best feckless and at worst possibly fascist. For another, the process of working with DC Comics, which published his work during his two great fertile periods in the mid-80s and late 90s, so embittered him to the industry that he has often repudiated his own work on corporate superheroes, just as it acquired pop cultural success: video games, action figures, spin-offs. Recently asked about the real-world political influence of V for Vendetta, he was characteristically blunt: “From my position, if I have had one of my ideas stolen from me and turned into yet another cash-generator for some abhuman corporation, then if it has at least escaped into the wild sufficiently to be of some symbolic use to today’s protest movements, that makes me feel a lot better about having written it in the first place.”

At the heart of this antipathy is DC’s hold on the legal rights to his co-creations Watchmen and V for Vendetta. Moore and Gibbons were promised that all rights would return to them when Watchmen went out of print, but it never did. Gibbons accidentally predicted what would happen in this arrangement back in 1986. “What would be horrendous, and DC could legally do it, would be to have Rorschach crossing over with Batman or something like that, but I’ve got enough faith in them that I don’t think they’d do that,” he told Neil Gaiman in a public interview preserved by the Comics Journal.

Moore never got his rights back and DC has spent many years revisiting Watchmen with lucrative anniversary editions, prequels, a movie, the forthcoming TV series and indeed Watchmen II, called Doomsday Clock, a work in progress with script and art by a different creative team. This will merge the fictional world Gibbons and Moore created with the universe shared by Wonder Woman, Superman and Green Lantern.

Moore’s efforts outside superheroics, such as From Hell, Lost Girls and A Small Killing, are often cited as proof of his literary worth. But his greatest contribution to English letters isn’t found in his additions to the growing canon of respectable graphic novels – a term Moore has said was invented to allow adults to “validate their continued love of Green Lantern or Spider-Man without appearing in some way emotionally subnormal”. It’s in his dazzling, quixotic overwriting, applied to trashy genre fiction with an ironic, but never cynical quality. This worked wonders on uncomplicated planet-tossers like Superman and Captain Marvel. And when he leaves behind the superhero hijinks, a lot of the fun leaves the writing along with them. Don’t get me wrong, the highbrow books are still brilliant; they’re simply not as enjoyable as the pulpy stuff.

Many fans have been left in the awkward position of liking Moore’s superhero comics a good deal more than he does himself. When Miracleman delivers his baby girl and turns his face toward the reader, his eyes abrim with tears, and his internal monologue proclaims, “These are the moments when we are real”, I have always agreed, despite the narrator’s being clad in a blue leotard.

Moore would be the first to tell you that seriousness isn’t always a virtue, but his was thoroughly transformative. And for many readers, myself among them, it was a great relief to be taken seriously as a reader of something supposedly sub-literate and stupid, to be treated with intelligence and care, and to be introduced to Moore’s rebellious brand of morality: his passionate feminism, his suspicion of authority and wealth, his love of normal people and veneration of togetherness, especially in the face of the hopelessness of the real world. His gifts for cruelty and horror inspired undistinguished competitors to enter the field, but his unexpected gentleness was what kept readers coming back to him.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion