If Ethan Stables, the 20-year-old man convicted on Monday of planning to kill attendees of a local gay pride event in Cumbria, was really bisexual as he claimed in court, why would he want to hurt other LGBT people? Sadly he wouldn’t be the first.

Many gay people know the most homophobic school bully often pops up in the local gay bar a few years later, but there are wider examples: Hollywood agents who bar clients from coming out, historical figures such as Senator McCarthy’s anti-gay lawyer Roy Cohn, who maintained till the end that the Aids-related illness that killed him was liver cancer, the countless homophobic politicians caught with male escorts. But self-loathing can turn deadly. Omar Mateen, who committed America’s most deadly homophobic attack at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida in 2016, pledged his allegiance to Isis but was also alleged to have made sexual advances towards men. His ex-wife said she believed he was gay.

We don’t talk about it much, but many people struggle to feel at ease being anything other than heterosexual, even years after coming out. We all grow up hearing homo- and transphobia, and, as I say in my book Straight Jacket, LGBT kids aren’t given magical earplugs. Research now shows how destructive shame can be. The Adverse Childhood Experience study led by Dr Vincent Felitti showed that the greater number of extreme negative experiences a child has, the greater the chance they will develop mental health problems in adulthood. The study showed the most damaging experience was not incest, as expected, but “recurrent chronic humiliation” – in other words, if you invalidate and criticise children over and over, you’ll dramatically increase the chance they’ll develop self-destructive mental health problems in adulthood. This should be front-page news.

Gay people are not the only ones to suffer such shame, but experts, both gay and straight, agree that gay kids are overwhelmed with it. Many of us grow up, come out and have wonderful and happy lives. For others, the journey can be rockier. Many bury their feelings, hoping they’ll go away, some psychologically “split”, like the heterosexually married men who believe anonymous internet hook-ups don’t count as gay if they happen in secret. Just this week I met a young man who told me he hated gay pride, hated effeminate men but crucially was trying to work through these feelings by talking about them. The gay community doesn’t talk about this enough, and when we do it’s often with judgment.

Perhaps Ethan Stables, who has an autistic spectrum disorder, was not able to have those conversations. Most people grappling with shame do not join extremist groups and plan to hurt people. But some do. Perhaps like former notorious 1980s neo-Nazi street fighter Nicky Crane, who also eventually came out as gay.

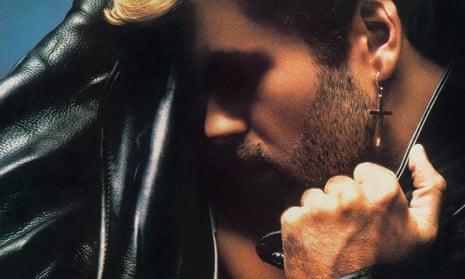

Talking about gay shame and self-loathing is not easy. It flies in the face of the message of gay pride that has dominated the gay rights movement of the last 50 years. But we must talk about it. Most people wrestling with shame hurt themselves. Disproportionate numbers of LGBT people suffer with self-destructive behaviour. At the end of 2016 we lost George Michael after years of mental health and addiction struggles. A year later, last November, 21-year-old American rapper Lil Peep died from a fentanyl overdose months after he came out as bisexual. Just last month, the 38-year-old presenter of the Discovery Channel’s Storm Chaser programme, Joel Taylor, died from a GHB overdose on an Atlantis gay cruise. All in a year that saw the usual reports of unsupported LGBT teenagers killing themselves, such as a 15-year-old in Stirling, after years of bullying, and a 16-year-old girl whose life-support machine was turned off after doing the same. And so it goes on and on, without much awareness or enough being done to address the situation.

Wider society has never cared about the children who struggle to come to terms with who they are. I was 11 when I realised I was gay and I could not cope. I needed support and someone to talk to. It wasn’t there. But it seems perhaps the gay rights movement has been caught napping, too. So much focus has been on changing laws and encouraging footballers to come out or on promoting sexual freedom – all important things – that we’ve missed the huge ground-level suffering of those struggling with the legacy of society’s gay shame, right under our noses.

It may not fit the narrative we wish to promote but there are huge numbers of people getting themselves into serious situations without enough support. Mental health isn’t “nice” or glamorous or about clinking champagne glasses at fancy events, it’s often about self-hatred, drugs and sex and people engaging in extreme behaviour, which many find hard to be sympathetic towards. But that is where the work lies.

Matthew Todd is a former editor of Attitude magazine