Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte wants to be friends, why isn’t China playing ball?

Philippine strongman finds himself between a rock and a hard place as Beijing refuses to let up on militarising areas it claims in the South China Sea

President Rodrigo Duterte is at sea again, navigating through unceasing Chinese militarisation off his shores on the one hand and growing domestic demand to assert the Philippines’ sovereignty on the other, even as he seeks friendlier relations with the Asian giant.

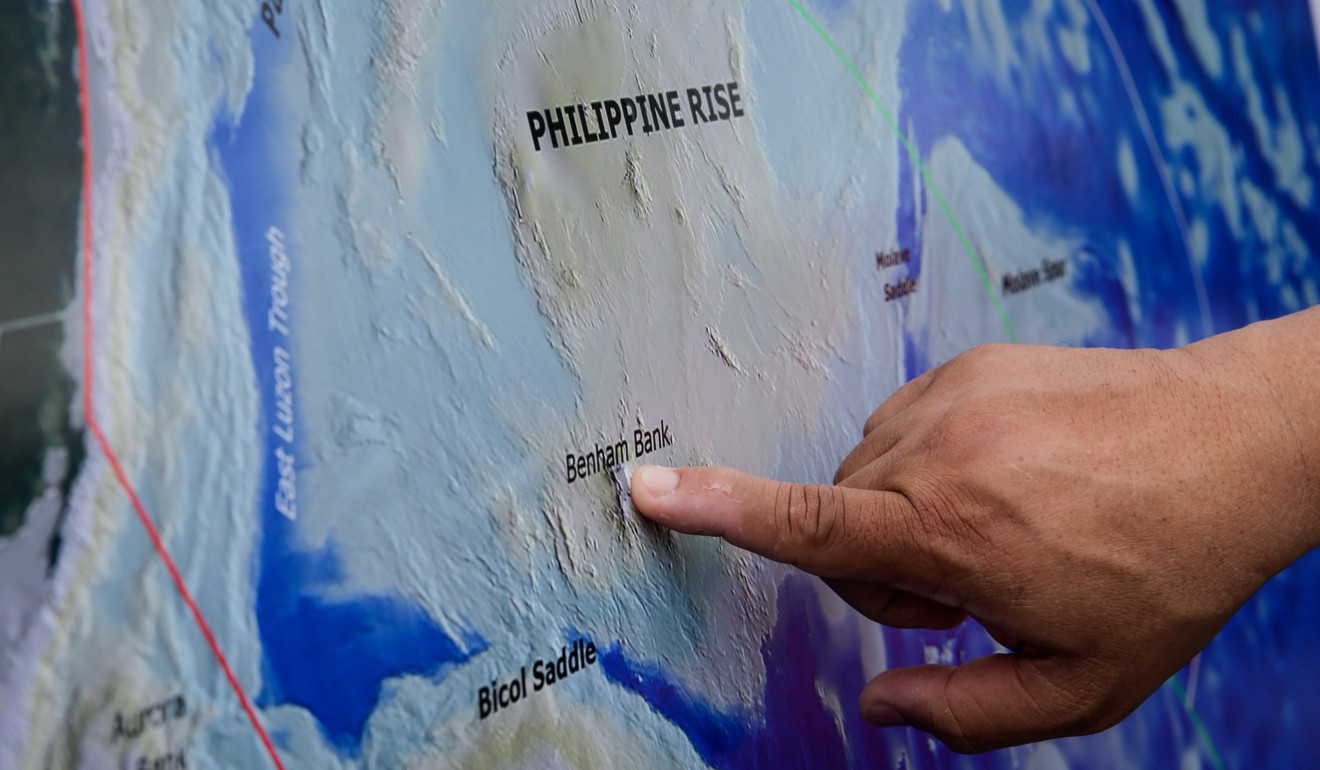

After announcing with much fanfare plans to visit underwater plateau Benham Rise to mark the first anniversary of its renaming as Philippine Rise, Duterte this week decided not to go the distance after all. Flying to a navy ship anchored far away at Casiguran Bay, he instead saw off the ship with 50 Filipino scientists to conduct scientific research in Benham Rise, leaving it well before it set sail.

What’s behind Beijing’s South China Sea moves – and why US patrols are making things worse

Beijing has also given Chinese names to five undersea features of the plateau, piling pressure on Duterte to act.

In 2012, the United Nations Commission on the Limits of Continental Shelf awarded Benham Rise to the Philippines, vindicating the country’s claim. This February Duterte halted all foreign marine explorations in the area without Manila’s permission, amid public disquiet over China’s research activities there.

“Next week, I’m going to set sail to Benham Rise and I will make a statement there that nobody but us owns this place,” he had earlier said in a speech, threatening to “go to war” if any other country lay claim to it. He did make the statement, proclaiming 500 sq km of the area as a marine protected zone off-limits for any commercial activity, but held fire on anything more provocative.

What now for Duterte’s China pivot as Marawi cements US importance for Philippines?

Jet skis spotted aboard the ship had triggered speculation he might ride them to Benham Rise. In the end, the president’s son and an aide rode the skis around the uncontested Casiguran Bay, about 290km from Benham, inviting the opposition’s barbs, as did his declaration on board the navy ship that Chinese leader Xi Jinping had promised to protect his presidency. “Xi’s assurances are very encouraging: we will not allow you to be taken out from your office and we will not allow the Philippines to go to the dogs,” he told the gathering.

Duterte plays a dangerous game in the South China Sea

This is the second time in recent weeks Duterte has backed out from aggravating the Chinese. Recently he reversed plans to raise the Philippine flag in the Pag-asa Island in the disputed Spratlys archipelago to mark the Philippines’ independence day, because, he said, he valued China’s friendship. “I need China more than anybody else at this time of our national life,” he said last month.

Duterte’s softly-softly approach stands in contrast to resentment in the country against what is seen as Chinese aggression in Philippine waters. Beijing has steadily expanded the seven features it occupies in the disputed Spratlys – which China calls the Nansha Islands – in the South China Sea, building artificial islands on at least three reefs and converting them into military bases. Fresh media reports this month of Chinese deployment of missiles on the three reefs have fuelled more anger.

“The president says he will take up the issue of island building with China later. But when? He says the Chinese weapons are not aimed at us, but who are they aimed at then? All our neighbours are our friends. How can we allow our land to be used to train weapons at our friends and allies?” says Roilo Golez, a veteran politician and former National Security Adviser.

Welcome to conflict tourism: how Chinese state firms are using the South China Sea

“Manila should protest. The Chinese will deploy combat planes in the Spratlys next, that’ll be the next stage of escalation.”

Within days of this conversation, the Chinese state media on Friday reported that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Air Force had landed long-range bombers for the first time on an airport in the South China Sea. The report does not specify when or exactly where but says the operation involved several H-6Ks taking off from an air base then making a simulated strike against sea targets before landing.

Setting aside the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s 2016 ruling in favour of Manila’s claims against Beijing’s in the South China Sea, Duterte has focused on strengthening diplomatic and economic relations with China by downplaying maritime disputes and distancing himself from the United States, its treaty ally. But America’s long association with its former colony and its key institutions such as the military and police, and the goodwill and soft power the US still enjoys in the country doesn’t make Duterte’s drift from a US-aligned foreign policy an easy one.

And China isn’t helping. It has responded to Duterte with investments but refuses to let up on fortifying the overlapping maritime zones it sees as its own.

“China is an ultra-realist power determined to project its power onto the Western Pacific to create its defensive shield against US power. The Philippines lies within what Beijing considers its defensive perimeter,” says Walden Bello, a prominent leftist voice in the country. “Beijing can be flexible with Duterte when it comes to economic aid and investments but it is inflexible when it comes to its geopolitical aims.”

What South China Sea rivals can learn from the Doklam border dispute

China’s strategy in the South China Sea is aimed at restoring its status as a major power in the region, displacing the traditional American sway in these parts. Assertion of its “core interests” in the waters encompassed by its “nine-dash line” claim – the sea boundary on old maps Beijing says proves its claim to most of the waterway – and building up its military capacity there are crucial components of this ambition. But the more China militarises, the more it puts Duterte in a bind, making his outreach to China look more like a helpless sell-out rather than the pragmatic economic partnership he wants to project.

To complicate matters for him, Beijing is not entirely convinced of Duterte’s China pivot either. China was never under any illusion that the Philippines would ditch its ties with the US under any circumstances, says Zha Daojiong, a professor at the School of International Studies, Peking University. “We never sensed an ‘either US or China’ calculation on Duterte’s part.”

Duterte’s popularity has held so far but Bello says if it starts to give way, the opposition and the military brass will start mounting pressure to confront Beijing. And herein lies Duterte’s biggest problem: the risk of a military conflict with China. “It will be massacre,” he said in a recent speech.

Why the US policy on South China Sea only helps China

Last month Admiral Philip Davidson, the incoming head of the US Pacific Command, told the US Senate Armed Services Committee: “Any [Chinese] forces deployed to the [Spartlys] islands would easily overwhelm the military forces of any other South China Sea claimant. In short, China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States.”

That leaves Duterte with very little room to manoeuvre. If China gets too aggressive, Manila may turn more and more to the US for support, says Roland Simbulan, an educator known for his advocacy against US military bases in the Philippines.

“But then the problem is whether the US will be willing to risk a military conflict with China to protect Philippine interests.” ■