Column: Burned horse trainer Martine Bellocq finds love, hope among the ashes

Sitting in a bedside chair at Vibra Hospital in Hillcrest, Martine Bellocq thumbs at the tracheotomy opening in her neck with reddish-white hands as visitors in protective gowns and gloves lock eyes and listen.

The horse trainer burned over 60 percent of her body during the deadly Dec. 7 fire at San Luis Rey Downs waited almost four months to speak, isolated in a burn unit. She’s braved a port in her chest, tubes flowing from her nose, three-times-weekly dialysis, eight skin-graft surgeries and the amputation of her lower left leg.

Talking matters so much, because Bellocq has so much to say.

When her prized colt Wild Bill Hickory refused to budge as ink-black smoke filled his stall and flames licked across from the far side of the barn, Bellocq decided she had one more shot. She grabbed a hose, doused herself from head to toe, and charged inside. The fire had other ideas.

“When it got so hot, my body started to burn,” Bellocq said Wednesday. “It hurt so much. I just walked out of the barn. He’ll find me. He’ll find me.”

Parked at the edge of her hospital bed a few feet away, her husband Pierre reached out a hand and spoke in a muffled whisper.

“I found you,” he said.

True love stories rarely unfold like airport paperbacks, the hulking heroes with flowing manes cradling Southern belles in absurdly sculpted arms. Reality is an exhausted husband helping a wife of nearly 42 years in and out of her wheelchair.

Sometimes, love reveals itself through simply finding a way, day after day, for someone impossible to live without.

“He’s the best husband,” Martine said. “Every day, he came. Every day, he supports me. He’s a wonderful man.”

Martine reached for a pair of sunglasses. She’s waiting on surgeries to both lower eyelids. More will follow.

“You’re really a rock star now,” Pierre said.

They’re facing the beast — the fire then, the ashes now — together.

Music soothes a hurting heart

When the quiet moments badgered at night, long after Pierre visited his comatose partner and buttoned up the horses at San Luis Rey, he reached for a DVD. The DVD.

Unable to talk with his wife for months on end, his companion became a banjo-playing Grammy winner. Pierre would pop in “Throw Down Your Heart,” the 2008 documentary about Béla Fleck’s African journey tracing the origins of his signature instrument.

As the twang of the banjo beckoned, images of the 46 horses who died that day would momentarily fade. As the toe-tapping took hold, the horrifying image of the Martine he found after being separated for just three life-altering minutes would release a little of its unforgiving grip.

“What struck me when I came to her was, the skin on her hands had literally melted down,” Pierre recalled. “It looked like she had white rubber gloves that were coming off her hands. It was skin, actually. You had bright red and white skin hanging down from the fingernails.

“Not a pretty sight.”

Pierre isn’t certain how many times he’s watched Fleck’s melodic wandering from Tanzania to Senegal. Twenty times? More?

“When I’m really depressed, I have that DVD,” Pierre said. “I saw a concert of his in Kentucky years ago and bought it there. It’s just fascinating as he goes through these small villages. It lifts me up every time I see it. I forget about everything else.”

There are so many questions. How did the blaze move that quickly? How did it hop-scotch, from palm tree to palm tree? There’s far too much to process, including some things that never will settle.

There’s the 180 or so seconds that Pierre rushed away to deliver a horse to a safer place. There’s the unfathomable fallout when he returned, Martine collapsed in a heap outside of the hellish furnace.

Pierre fought the urge to unravel at what he saw. He raced to find a golf cart and drove his wife to emergency personnel staged at the San Luis Rey Downs entrance.

“You’re almost doing things mechanically,” Pierre said. “There’s so much going through your head. You have to act. It’s an emergency situation. You feel like breaking down and crying, but you know you have to do something.

“You either completely lose it or continue acting.”

As an ambulance sped toward Palomar Medical Center, the one word Martine managed to utter rang in Pierre’s ears. Billy? He ran back to the stall to see if anything could be done for the colt.

“The first thing I saw was Billy, in the middle of the shed row in front of his stall,” said Pierre, 66. “He laid down, his legs burned to the knees and the hocks. There was nothing below the knees. He must have thrown himself into the shed row, in flames.

“It’s the most horrible scene I’d ever seen.”

A small army of medical personnel cared for Martine. Pierre knew, though, that he had to take care of himself so he could aid the recovery, as well. That’s what Martine had done, about a decade ago, when some mis-timed medications caused Pierre’s blood sugar to plummet as he slipped into a diabetic coma.

“His heart stopped. They told me he was dead,” said Martine, 64.

Then she made the sound of paddles offering an electric jolt: “Boom! Boom! Then he came back to life. I was there for him. He’s there for me.”

Martine’s message: ‘You can make it, too’

In 1974, two French citizens crossed unlikely paths in Aiken, S.C., because of not one, but two, somewhat comical misunderstandings.

While living in the Parisian suburb of Maisons-Laffitte during the early 1950s, Pierre’s father of the same name — a blossoming cartoonist better known in racing circles as Peb — displayed his art at a café. John Shapiro, then owner of Maryland’s Laurel Park, came to the area to recruit horses for an international race.

Shapiro marveled at the likenesses of jockeys and struck up a conversation, but Peb didn’t understand English. Peb decided an off-hand comment about working for his new admirer in the United States had been real.

“My father took it literally, took his $24 and showed up with the horses (for the race),” the younger Pierre said. “Shapiro barely remembered him, but gave him a job to do the poster and program for the race.”

Eventually, Peb landed positions with the Daily Racing Form and the Philadelphia Inquirer as a young son with an eye for the sport tagged along.

Meanwhile, Martine had developed a niche in the sport by becoming one of the first female exercise riders in France. When a colleague in New York told her a job as a “groom” could be hers, she hardly hesitated — although not for the reason she thought.

“In France, a groom is a bellhop,” Pierre said. “She thought she was going to come over and work at a hotel. It turned out to be a groom on the racetrack.”

Jobs landed both at the horse-training center in Aiken. They met at a Christmas party. Two years later, they were married.

“It’s strange, maybe fate or something,” Pierre said.

When the Bellocq’s daughter moved to the Temecula area, the lure of two grandchildren brought Pierre and Martine to San Luis Rey Downs. They’d sniffed success before, with Pierre working as an assistant trainer for 2004 Kentucky Derby runner-up Lion Heart.

They decided to build their own operation in Southern California, at San Luis Rey Downs. Pierre’s first impression: “I loved it.” The one-time host of legendary horses that included Sunday Silence, Fusaichi Pegasus, Cigar, Azeri and Ferdinand offers everything from an auxiliary track, regulation-sized equine pool and stationary training gate.

In a few fateful minutes, the place that produced all those smiles delivered unimaginable sadness.

When Martine finally climbed from her coma, a flood of questions followed. She had lost all sense of time. Pierre said to Martine, it was as if it was Dec. 8 — the day after the fire. She asked about the horses and the other workers.

“I didn’t know it was 2018,” she said. “I thought it was 2017. I was in outer space.”

As Martine soaked up the devastating whole of it all, she made a critical decision. She would embrace the silver linings, she would relentlessly search for hope and she would fight just as hard as Pierre had while she was trapped by the darkness.

In physical therapy sessions, she’s traveled 40 to 50 feet with the help of a walker. Doctors who warned that a kidney transplant would be likely within a year founded themselves stunned at a turnaround that ended her dialysis treatments.

On TV one day, a 5-year-old girl dancing with one leg mesmerized Martine.

“It made me feel like, if that kid can do it, I can do it,” she said.

Moments later, Martine glanced down at what’s gone and explained the promise of what’s to come.

“It’s OK,” she said. “I’ll get another one.”

Again, Martine manipulated her throat. There’s so much more to say.

“I want to send a message to people who are burned and handicapped to hang in there and believe everything will be OK,” she said. “There are a lot of people like me who need some help. I wish I could go see those people and talk to them and say, ‘Hey, I made it — you can make it, too.’ ”

Will she return to San Luis Rey? Of course.

“It was just an accident,” said Martine, who was moved Friday to a North County facility closer to home. “It was not anything mean by the horse. It’s not the horse’s fault.”

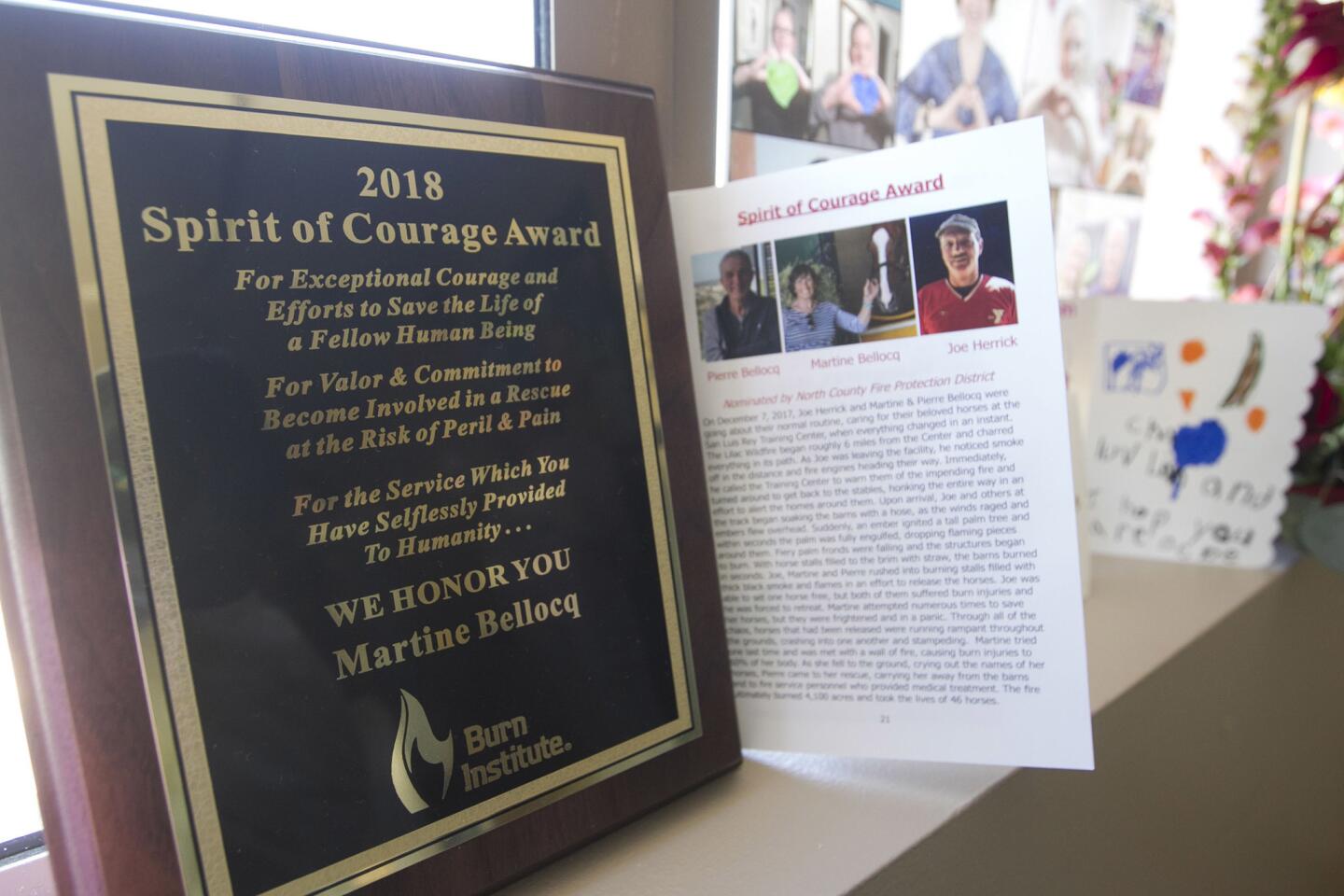

On a hospital room window sill rests a Spirt of Courage award from San Diego’s Burn Institute. It honors both Bellocqs and another burned trainer, Joe Herrick. Martine hardly needed the reminder about Pierre.

Her hero’s always been there.

Sports Videos

Go deeper inside the Padres

Get our free Padres Daily newsletter, free to your inbox every day of the season.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.