“I am the one person you never want to meet,” Kevin Moran says quietly into the microphone. He’s talking to the adults in the room, about half of the 200 people gathered in the gymnasium of St Peter’s boys high school on New York’s Staten Island.

After a pause, Moran turns to the other half – teenagers who have been asked to sit apart from their parents – and adds: “You will never meet me when the time comes because you will be dead.”

Moran is a funeral director with 30 years’ experience and he was speaking at a ‘Scared Straight’ seminar designed to give teenagers a glimpse into the realities of drug addiction. Modeled after the inmate-juvenile interventions that took off in the late 1970s, the event features local speakers with harrowing personal stories: a heroin addict who lost a leg after weeks in an overdose-related coma; a husband whose young daughter spent the night with her dead mother’s body after the mother had overdosed.

When it’s Moran’s turn to speak, he focuses on details from his work. He asks the teenagers to imagine the horror of watching anguished family members punch the bodies of their dead loved ones during viewings at the funeral home.

Moran has been a regular speaker at the Scared Straight seminars since 2014 and attendees often remember his speeches as the most heart-wrenching. “I got chills,” a 13-year-old said after hearing Moran speak. Occasionally, his audiences are left in tears.

Yet despite dozens of talks in schools, treatment centers and seminars over the past four years, Moran doesn’t see himself an activist or a crusader. “I’m just trying to do whatever I can to hopefully prevent somebody from going down this road,” he says.

As the last stop for well over 100 overdose victims in the last four years, it’s a road Moran knows all too well.

A borough ravaged by addiction

For nearly a decade, Staten Island has struggled to combat the opioid epidemic ravaging its communities. The crisis peaked in 2016 when the borough suffered from the highest per capita rate of opioid overdose deaths in New York City at 32 per 100,000 people.

Through a combination of education, access to treatment, and the increased use of Narcan, a nasal spray that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, that number dropped last year by 15%, but advocates worry that the statistic may be misleading. While the number of overdose deaths on Staten Island declined, the number of overdose victims saved by Narcan soared. “This battle is far from over,” Staten Island district attorney Michael McMahon told reporters in January.

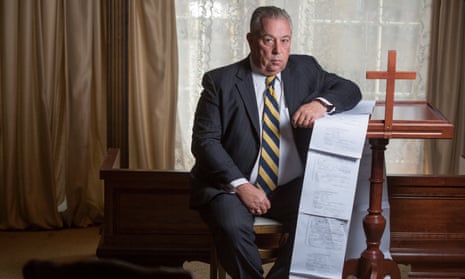

At St Peter’s, Moran highlighted this point. Halfway through his talk, he paused, raised his hand and let a scroll of printed pages unfurl to the floor. A young middle-schooler was picked from the audience and asked to read from one of the pages.

“You can’t even pronounce it!” Moran exclaimed as the teen stumbled over the first word. “It’s acetylmorphine,” Moran told the audience. The substance is often found in the body following a heroin overdose.

Each page in the scroll was a copy of the death certificate of someone Moran buried in the last four months. Four certificates were from the previous week.

‘It’s not a moral weakness or a choice’

In person, Moran, with broad shoulders and slicked-back gray hair, exudes a warm, sympathetic demeanor that stands in contrast to his no-holds-barred speaking style. He’s a 57-year-old father of two grown daughters and joined the funeral home business because he saw it as a noble endeavor. He never thought of himself as much of a public speaker.

Four years ago, Moran got a call from Alicia Palermo-Reddy, a nurse who earned the moniker “Addiction angel” for her outreach efforts. The support groups she organized had outgrown her backyard and were filling auditoriums and gyms. Reddy wanted Moran to speak at one of the first large-scale events geared at educating young people. “We have to step it up a notch,” she told him. “We have to scare the crap out of them.”

Moran knew he had seen enough at the funeral home to oblige. “It’s become something I take very personally,” he says.

The response has been overwhelming. Reddy’s Scared Straight forums are almost always at capacity. “We’ve had as many as 700 people before,” she said. But despite their popularity, studies have shown that fear-based tactics like Scared Straight are largely ineffective.

“Scared straight comes from a good place, because I think a lot of times family members and friends just feel desperate and they are trying to make a big impact,” says Kelly Dunn, an associate professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Johns Hopkins University. “But they don’t realize that perhaps it’s not a moral weakness or personality – a choice.”

Dunn believes that treating the physiological effects of withdrawal symptoms with methadone and Suboxone gives addicts the best shot at managing their addiction, even if those treatments continue for years.

Jennifer Doren, who brought her kids to the seminar, disagrees. “I think it’s not enough,” she said. “It needs to be in the schools and more often.” She added that she would be bringing her kids back to the next meeting.

Moran, too, understands that his style may not be for everyone, but his message is stark by design. “There’s nothing I can do for the person who died,” he told the audience at St Peter’s. “My job is to help the living.”

For Moran, the young people who seek his guidance after talks are evidence enough that his message is getting through. “You can’t take a paintbrush and apply one color to every person and say that that is the proper way to reach them,” he said.

For now, Moran will keep speaking at schools and rehabs and Scared Straight; wherever he thinks he can help. But he’s mindful of the toll that the opioid epidemic has had both professionally and personally. “It’s coming from the heart,” he says when asked about the bluntness of his talks. “Once you get hardened, you need to get out.”