Readers Don't Need the Nobel Prize in Literature

The cancellation of the 2018 award is an opportunity to remember that great works of writing aren’t decided by committee.

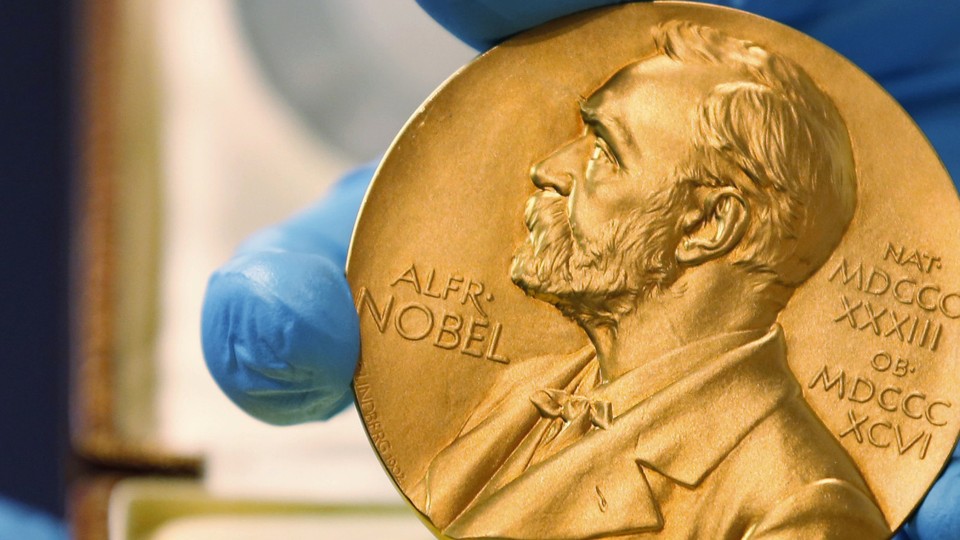

You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone, Joni Mitchell told us. So now that the Nobel Prize in Literature is gone—the 2018 prize will be postponed, as the Swedish Academy deals with the fallout of a sexual harassment scandal—it seems worth asking what, exactly, the prize gives us. Will we miss it this October, when the chemists and physicists and economists are buzzing about their laureates, and the writers are left out? Some people will, surely—the publishers who capitalize on the prize to sell the winner’s foreign rights, and the journalists for whom it provides an annual headline. And of course the small group of writers who are regularly rumored to be Nobel contenders—Philip Roth, the Syrian poet Adonis—must be furious.

But what about actual readers? Will a year without the Nobel deprive us of the chance to make the acquaintance of a writer we would love and admire? Here the answer is a pretty clear no. For decades, the choices of the Swedish Academy have failed to provoke much interest from American publishers and readers. (This seems only fair, since over the same period the Swedish Academy has resolutely ignored American literature: The last American writer to win the prize was Toni Morrison, in 1993. No, Bob Dylan doesn’t count.) When was the last time you heard someone say they were reading J.M.G. Le Clézio or Herta Müller?

This is not just because American readers are resistant to fiction in translation, as publishers often complain. On the contrary, over the last two decades, many foreign writers have made a major impact on American literature. W.G. Sebald, Roberto Bolaño, Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard, and Haruki Murakami have all been celebrated here and around the world; none has won the Nobel Prize. But then, the failure of the Swedish Academy to reflect the actual judgment of literary history is nothing new. If you drew a Venn diagram showing the winners of the Nobel Prize in one circle and the most influential and widely read 20th-century writers in the other, their area of overlap would be surprisingly small. The Nobel managed to miss most of the modern writers who matter, starting with Henrik Ibsen at the beginning of the 20th century, and continuing through Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Anna Akhmatova, Jorge Luis Borges, Aimé Césaire, and many others.

Does this mean that the Swedish Academy has been particularly incompetent in administering the prize? Would a different group of critics and professors in a bigger, more cosmopolitan country have done a better job at picking the winners? Very possibly; and one salutary side effect of the cancellation is to draw attention to the Academy itself. Like every literary prize, but even more so, the Nobel’s prestige requires that we not pay too much attention to the judges who award it. The members of the Swedish Academy do not hide their identities, but they are completely unknown outside of Sweden, and press accounts of the prize rarely name them; in the mind of the general public, the Nobel basically descends from the sky to anoint the winner. But it is nothing more or less than the decision of a particular group of readers, with their own strengths and weaknesses. As this new scandal has shown, they are just as susceptible to power dynamics and political infighting as the members of any other institution.

But the problem with the Nobel Prize in Literature goes deeper. No matter who is in the room where it happens, the Nobel Prize is based on the idea that merit can best be determined by a small group of specialists. This may make sense for the prizes in the sciences and social sciences, since those fields are less than penetrable to anyone but fellow practitioners. Even in the sciences, however, there is a growing sense that the tradition of awarding the prize to just one or two people distorts the way modern science is actually practiced today: Most important discoveries are the work of teams, not of individual geniuses brooding in isolation.

Literature is at least produced by individual authors; but in this case, the Nobel’s reliance on ostensibly expert judgment runs into a different problem. For literature is not addressed to an audience of experts; it is open to the judgment of every reader. Nor is literature progressive, with new discoveries superseding old ones: Homer is just as groundbreaking today as he was 2,500 years ago. This makes it impossible to rank literary works according to an objective standard of superiority. Different people will find inspiration and sustenance in different books, because literature is as irreducibly pluralistic as human beings themselves.

Good criticism helps people to find the books that will speak to them, but it doesn’t attempt to simply name “the most outstanding work,” in the way the Nobel Prize does. It is impossible to name the single best writer for the same reason that you can’t speak of the single best human being: There are too many different criteria for judgment. That is why the “canon” has always been a false metaphor when it comes to literature. A book earns the status of a classic, not because it is approved by a committee or put on a syllabus, but simply because a lot of people like it for a long time. Literary reputation can only emerge on the free market, not through central planning; and the Swedish Academy is the Politburo of literature.

Of course, the Nobel Prize will be back in 2019—it serves the interest of too many people to be permanently canceled. But this October will be a good time to celebrate its absence by remembering that, in the words of the great 18th-century critic Samuel Johnson, “by the common sense of readers uncorrupted with literary prejudices … must be finally decided all claim to poetical honors.”