How a Chicago Dive Bar Exposed Corruption and Changed Journalism

In the 1970s, the Chicago Sun-Times used the Mirage as a front.

In late January, a no-frills Irish pub in Chicago, the Brehon, invited a small selection of guests for a night of light appetizers and drinks. The gathering wasn’t a supper club, or a private party. The event commemorated the 40th anniversary of the bar’s previous iteration, the Mirage Tavern, and the paradigm-shifting investigation that took place within it.

While the Mirage had the appearance of (and all the fixings of) a good ’70s dive bar, including dirt-cheap drinks and games, it was actually a front. In 1977, a group of journalists from the Chicago Sun-Times bought the derelict watering hole and operated it in secret for several months. The Mirage turned into one of the most contentious, precedent-setting experiments in investigative journalism to date, which, in turn, revealed an intricate web of corruption, bribery, negligence, and tax evasion.

It’s well-known that Chicago has a long history as a hotbed of organized crime and political corruption. But players and civilians alike aren’t often willing to talk to journalists about the nitty-gritty of how this happens. At least, not on the record. That’s why Upton Sinclair went incognito in order to reveal the horrid conditions of Chicago’s meatpacking plants at the turn of the century. It’s also what led Pam Zekman to convince the Chicago Sun-Times that they should buy a dive bar in the name of investigative journalism.

Before coming on as a reporter for Sun-Times, Zekman had been part of a team at the Chicago Tribune that brought a series of abuses, including medical malpractice, to light by going undercover at hospitals and nursing homes. By the mid-1970s, Zekman had become entrenched in reporting on Chicago’s underground network of corruption and bribery. Frustrated that no one would talk to her for a story, though, she took a cue from her past undercover work and, along with her mentor George Bliss, Zekman proposed that a team of reporters should pose as the owners and operators of a bar in the city’s River North neighborhood.

The Tribune declined, but the Sun-Times was up for it. So they partnered with the Better Government Association, a watchdog group that looked into local corruption, and bought themselves a watering hole. Why a bar, though? “We started getting phone calls from businesses that were complaining about having to pay a steady stream of inspectors that come into the restaurants and bars looking for payoffs to ignore city violations,” Zekman said in an oral history.

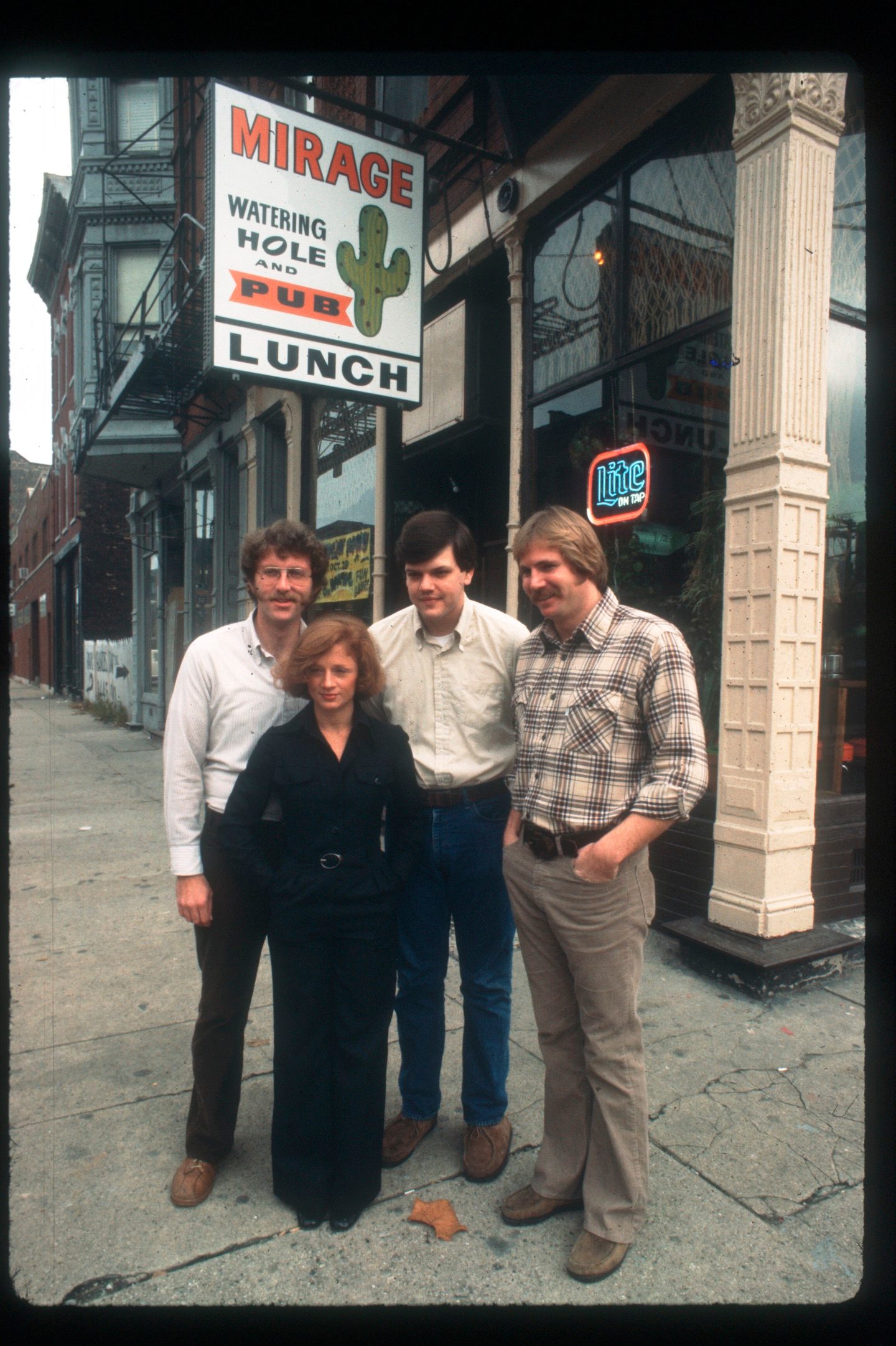

The group settled on a tavern known as the Firehouse, located on the corner of North Wells and Superior, due to how close it was to the paper’s offices. They renamed it the Mirage. There wasn’t anything illustrious about the place. As one of the reporters, Zay N. Smith, remembers: “It was dirty, badly kept, just kind of a hang-out for a few tipplers in the neighborhood.” Zekman and Bill Recktenwald (of the BGA) posed as the married owners of said bar, “Pam and Ray Patterson.” People were more than willing to talk to them now—starting with the business broker who, upon helping the two buy the the joint, told them right out the gate that he’d lend them a hand paying off building and fire inspectors with cash, and doctoring their tax documents. “When we were a reporter and an investigator, people wouldn’t talk,” Recktenwald remembers. “Now that we were a husband and wife pretending to buy a tavern, people wouldn’t shut up.”

Telling their own newsroom was a different story. Zekman and Recktenwald aside, only a handful of other people were involved. That included Smith (who went by “Norty” for the project) and photographers Jim Frost and Gene Pesek, who posed as repairmen and rigged cameras through the ceiling to capture city officials’ shakedowns when they happened. Few others knew what the team was working on, not even the paper’s publisher.

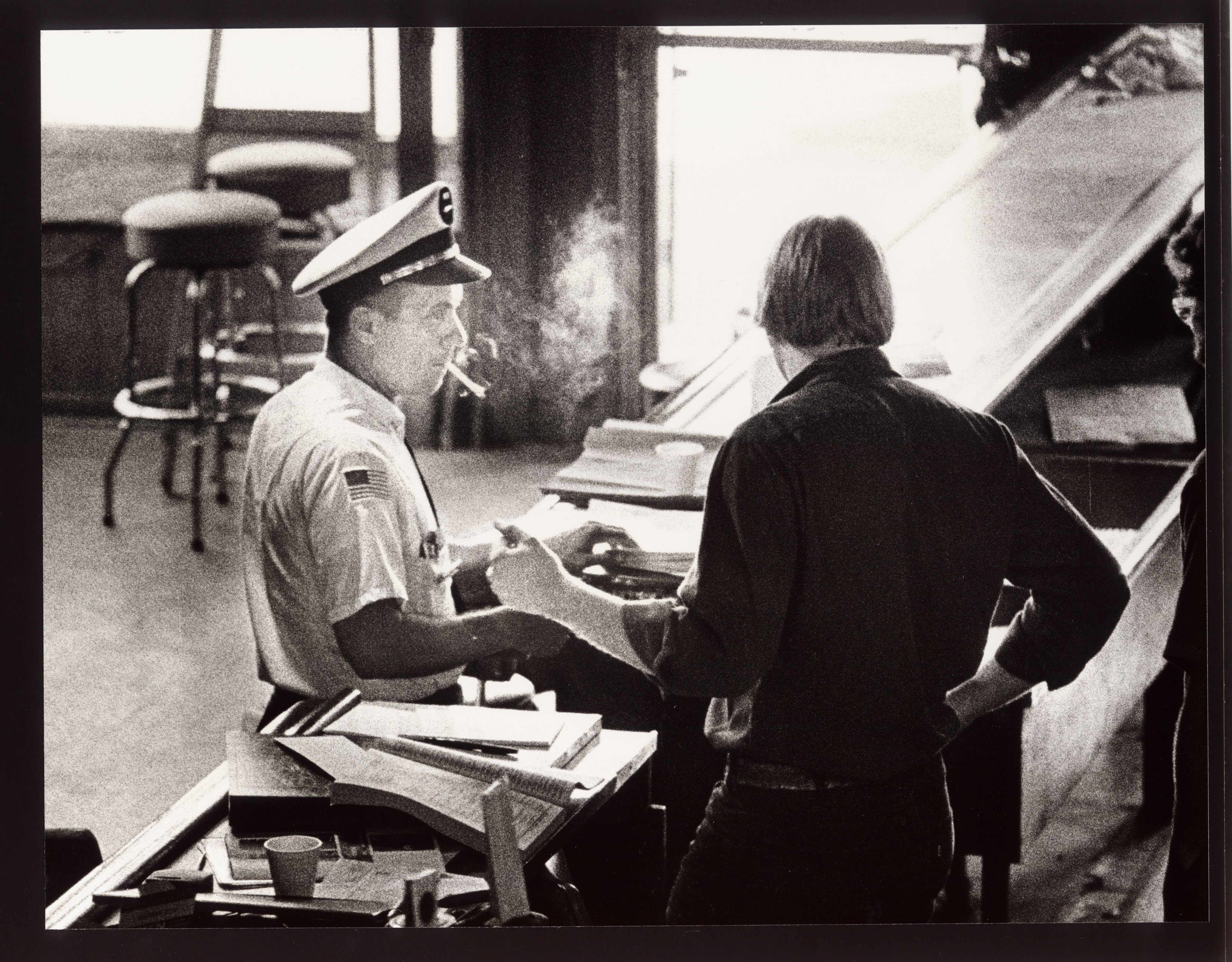

Keeping the secret close paid off in staggering ways, though. For one thing, the journalists quickly figured out how corruption manifested itself: All they had to do was leave cash in envelopes for the bevy of officials, who then stamped their approval regardless of the place’s condition. And the Mirage was in shoddy shape, to say the very least: The place was structurally unsound, with leaky pipes, bathrooms that weren’t up to code, and a maggot-infested basement. Which meant that it was only a matter of time before the inspectors came around, and they did pretty much immediately, shaking down the crew for about $10 to $100 for each time they looked the other way.

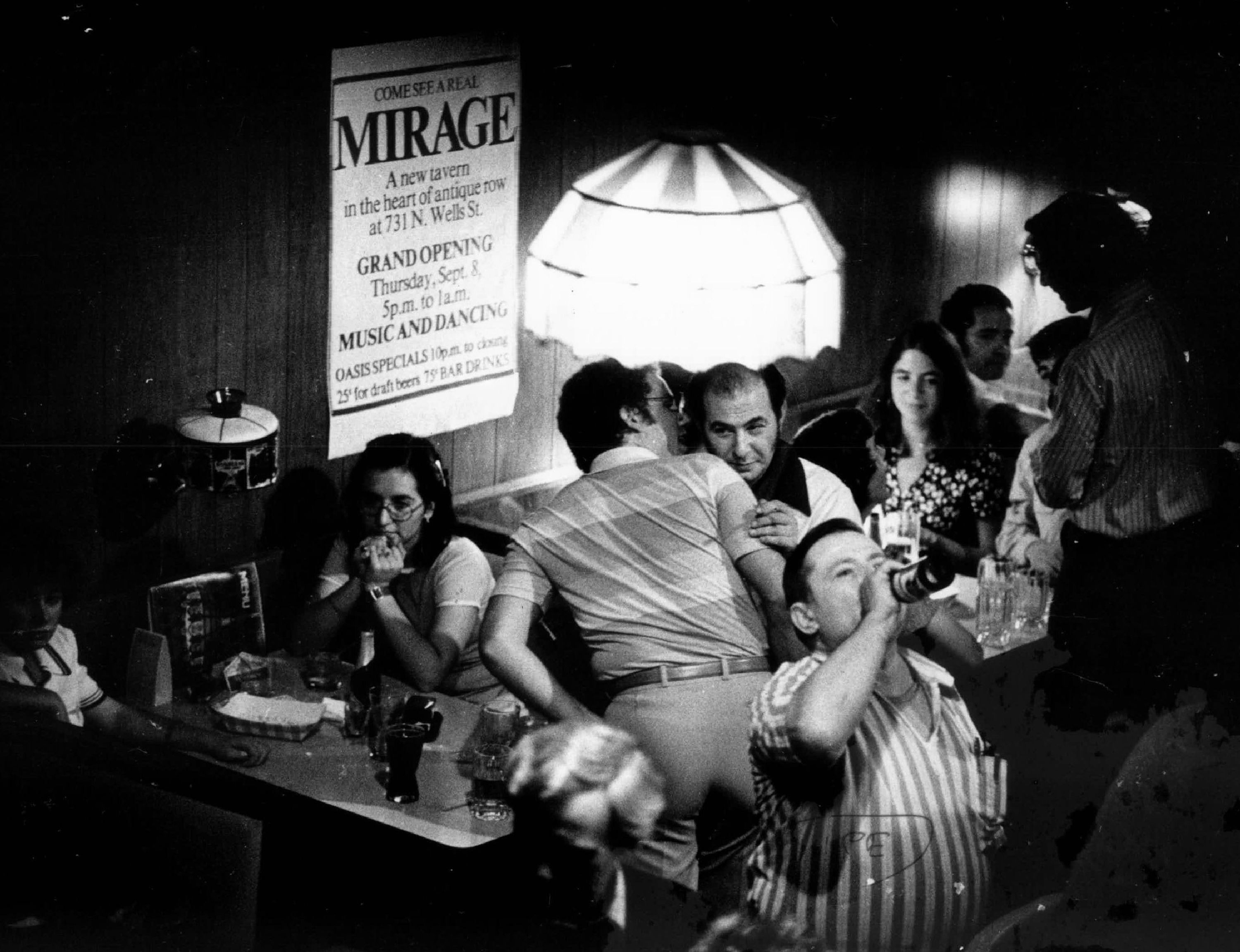

When the bar opened, people didn’t think too much of it. It was just another place to get a cheap drink (the “Oasis” special during the grand opening featured draft beers for 25 cents, and drinks for 75). As Zekman and Smith would later write of the Mirage in the Sun-Times: “It looked like any neighborhood tavern in Chicago. The beer was cold, the bratwursts hot.” The likes of Peggy Lee’s “Fever” whirred on the jukebox, and the drinks flowed, even though none of the Mirage “staff” knew how to bartend: Zekman once recounted that she’d thought that an order for a beer and a shot meant putting a shot in the beer itself. They aroused little suspicion, even though one day, a regular apparently said out loud: “I’ve figured it out, I’ve finally figured it out, this place is a front! It’s gotta be a front for something.”

The experiment didn’t last very long. After four months, the Mirage shuttered, and the team went to work. Beginning on January 8, 1978, the writers published the first of a 25-part massive exposé series. Right there, on the paper’s A1 page, a Chicago Fire Department lieutenant was photographed foregoing an inspection, and taking money instead. The reports are astonishingly detailed, sparing no one in the discoveries of a “payoff parade” and schemes where contractors acted as go-betweens for inspectors. One story detailed health inspectors awarding passed inspections in spite of a basement “so foul that even the vermin seemed to be dying.” Another health inspector, Robert Hansen, marked the Mirage as a clean premises although the ooze caking the basement floor was later revealed to be coated with rat and human droppings, among other microorganisms.

Chicago waited with bated breath for each of the series installations to drop, and the story quickly went international. The clampdown on corruption was swift and lasting, too. Eighteen city electrical inspectors were convicted of bribery by the following year, the feds investigated City Hall’s inspection system, and a task force known as the “Mirage Unit” was dispatched to investigate tax fraud. But when the series was up for a Pulitzer in 1979, Ben Bradlee, then-executive editor of The Washington Post and board member for the organization, led the charge for it to be stripped of the Local Investigative Reporting award. His fear was that the award would set a precedent and “could send journalism on a wrong course,” though it wasn’t the first time someone had been awarded a Pulitzer for going undercover. Not to mention that the Mirage project exposed, as the Post itself put it, “a systematic pattern of bribery and tax fraud that could cost the city an estimated $16 million in sales-tax revenues a year.”

While the paper did not win the Pulitzer, it became a textbook example of the ethical quandaries that undercover reporting poses. It also kicked off an ongoing debate, which is still taught in many journalism classes and name-checked in newsrooms today, about whether or not going undercover defies one of journalism’s main no-nos: reporters misrepresenting themselves in order to extract information from their subjects. It’s also telling of the Mirage’s impact that, 40 years later, an event at the former pub, with the journalists-cum-bartenders present, can still pack a room. “I would never claim we stopped corruption in Chicago,” Zekman clarified to the crowd at Brehon’s in January. “But I know that it had a huge effect on the inspectors. It made them think twice.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook