Last week, Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine was longlisted for the Women’s prize for fiction. The debut author, who has gone from writing competition to publishing bidding war to the Costa first novel prize, joins Joanna Cannon, with her second novel Three Things About Elsie. What’s more surprising than two relative newcomers sitting alongside heavyweights including Arundhati Roy and Nicola Barker is that these novels are decidedly upbeat accounts of the kindness of strangers.

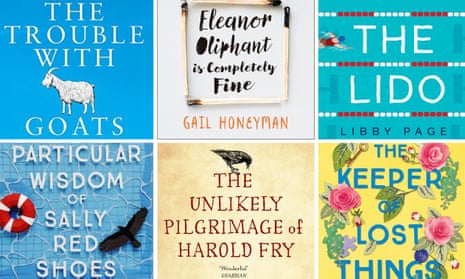

Branded “up lit” by publishers, novels of kindness and compassion are making their mark on bestseller lists, with Ruth Hogan’s The Keeper of Lost Things also proving a hit, and this summer’s The Lido by Libby Page continuing the positive trend.

Up lit arguably took off two years ago with the publication of Cannon’s debut The Trouble with Goats and Sheep. The novel – which went on to become a bestseller in both hardback and paperback – centres on 10-year-old Tilly and her best friend, Grace, endeavouring to uncover the whereabouts of their missing neighbour. Set in 1970s English suburbia and filled with tenderness, companionship and nostalgia, it is, according to former NHS psychiatrist Cannon, an exercise in wish fulfilment: “I write about communities, kindness and people coming together because that’s the society I wish for. I write what I’d like to happen.”

It’s perhaps unsurprising that in our increasingly busy and fragmented lives we are attracted to novels in which strangers demonstrate compassion. In Hogan’s forthcoming novel, The Wisdom of Sally Red Shoes, her protagonist overcomes grief at the loss of her child with the help of people she meets and befriends. For Hogan, the success of these novels is twofold: “I think as a society we’ve become much more isolated. On trains, buses, even just walking along the street, everybody is connected to their phones or their tablet or their laptop. Nobody is even looking at anybody else any more. We’ve become very insular. And yet when something happens that requires kindness it bursts out. I do think people are inherently kind.”

But up lit isn’t simply a means of sugar-coating the world. Rachel Joyce, author of international bestseller The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, stresses the importance of light and shade. “It’s about facing devastation, cruelty, hardship and loneliness and then saying: ‘But there is still this.’ Kindness isn’t just giving somebody something when you have everything. Kindness is having nothing and then holding out your hand.”

Many of the characters are society’s outsiders: from Eleanor Oliphant’s acute social awkwardness and Sally Red Shoes’s eccentricity, to isolated 84-year-old Florence, the protagonist of Three Things About Elsie, these books embrace difference, idiosyncrasy and those who are either marginalised or overlooked by society. For Joyce, whose new novel The Music Shop captures two protagonists burdened by painful emotional baggage, the process of creating flawed characters is inextricably linked with compassion: “I like writing stories about broken people who become fixed, which seems to me, in essence, an act of kindness.”

The idea that it is possible to fix what is broken – whether individuals or communities – is particularly compelling in today’s fractured political landscape, and goes some way to explaining why these novels are resonating with readers. “When the world is absolutely out of control,” says Hogan’s publisher Lisa Highton, “there’s a rather delicious sense of the pieces of the puzzles of these [characters’] lives coming together. I’m not publishing these books to make a statement, but like most readers I’m connecting with that humanity and warmth and a sense that you can fix things yourself.”

Redemption is often to be found in unlikely friendships – between the very old and the young, people of different nationalities, or those who have little in common superficially. At a time when tensions around immigration are running high, and certain media are fuelling fears about “the other”, the depiction of surprising alliances is both reassuring and uplifting. What each of these novels offers is the possibility that there can be not only common ground, but friendship and love between disparate people. As Cannon says of her new book: “It’s about the threads that join us. There are fundamental similarities between all of us that should unite us. Instead of looking for differences between people – and being afraid of difference – we should be celebrating it.”

These novels also share a strong sense of community. In The Music Shop, shopkeepers join forces to prevent a big property company from redeveloping their street. The staff and fellow residents at Florence’s nursing home unite to help the heroine solve a decades-old mystery in Three Things About Elsie. And in The Lido, a young reporter and an elderly widow energise local residents to save the local swimming pool.

As Cannon says, the current political landscape “feels very treacherous and very fragile. When we look around us and see that fragility and that uncertainty we look for something we can hold on to. Community is a brilliant antidote to that fragmentation. It makes us feel more secure to be drawn to a sense of purpose and a sense of place.”

Novels of kindness are infiltrating bestseller lists, which have been dominated for more than half a decade by psychological thrillers, led by Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl. In 2016, after the EU referendum, it seemed readers might turn instead to fantasy or science fiction as a means of escape. In fact, says Hogan, although “there has been this huge trend for crime fiction, with Trump and everything else our real life is dark enough. I think people are returning to the idea of fiction as an escape. And usually if we want to escape from the real world, we want to escape to a better world.”

What these novels offer – beyond a template of kindness, community and friendship – is hope. As Hogan says: “No matter how bad things are, there is a way forward. I want my writing to focus on how you can find joy and happiness even when you’ve had a really tough time and even when things aren’t going your way.”

There is a hope, too, that the compassionate spirit of these novels will rub off on readers. “I think any book you read changes you,” says Cannon. “I hope people read my novels and feel that sense of community, feel they want to go out there and do what the book has explained is important.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion