Depression

What to Do If You Are Depressed: Relationships

A blog series guiding folks who are depressed.

Posted July 25, 2019

Welcome to Part XIII in our “What to Do If You Are Depressed” blog series. The prior blog described emotions and learning how to process them adaptively. Today we explore one of the most central human concerns, relationships. Specifically, we examine four kinds relationship problems that connect to depression (i.e., loss, rejection, isolation, and loneliness), and we briefly review attachment and interpersonal styles and conclude with offering some suggested readings on relationships and depression. (See here to start the series).

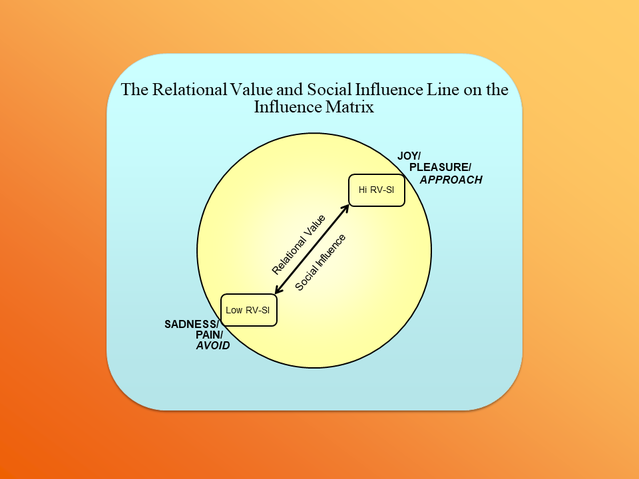

Few things nourish the human soul more than love. But what is love and why is it so central? According to the unified theory, human beings have a core “relationship system” that guides them in their social worlds. Being loved, in its most general form, refers to the experience of being known and valued by important others—it is one’s felt sense of having relational value (RV). An important and related variable is social influence (SI), which refers to the extent to which one can move others to act in accordance with one’s interest; it is one’s social resources or social capital.

The human relationship system is centrally organized around relational value and social influence—humans seek both in their exchanges with others. This is called the “RV-SI” line on a map of the human relationship system called the Influence Matrix (see here). This refers to the fact that people will have both a general sense of RV-SI (high or low or somewhere in between), and they will subconsciously track losing or gaining RV-SI in social situations and feel accordingly.

Relational nourishment refers to the extent to which folks have their relational value and social influence needs met across their development. There are four primary relational domains that we humans track for nourishment: 1) family; 2) friends; 3) lovers, and 4) groups or communities we belong to. Thus to understand a person’s relationship system and status it is important to reflect on the extent to which a person has felt known and valued across these four areas. We can start with one’s place in one’s family, most notably an infant's "attachment" to its primary caregivers and then track the other relationships in one's family of origin. By kindergarten, friends become central, and so has one's place in the peer group and larger sense of belonging (or not). In adolescence into young adulthood, the domain romantic love emerges as key. Problems in these domains set the stage for what might be called "relational malnourishment," which is one of the key causes of depression.

There are four kinds of relational problems people with depression often face. First, there is the loss of an important other, either via death, dissolution, or other disruptive forces. The loss of the loved one is the focus of Freud’s primary work on depression, Mourning and Meloncholia. Freud argued that individuals long for union with their lost loved ones; this is normal mourning. However, he argued that some individuals (often unconsciously) cannot get over the loss and end up feeling paralyzed, dejected and rageful about the unfairness of it all. Ultimately, this rage would be subconsciously directed inward, giving rise to a depressive shutdown (melancholia).

Rejection is the experience of being criticized, disrespected, abused, or unwanted. It is a direct attack on the need for relational value and social influence, and thus it is one of the most painful things a person can experience. Chronic rejection is one of the strongest causal predictors of depression.

Social isolation refers to folks who have few opportunities for connection and influence. Thus, a person in a strange land or who made no friends would experience social isolation. It is low social influence situation.

Loneliness is related to social isolation, but it is also different. It is the felt sense of not being truly known and valued. Thus, a person might on the surface appear to have lots of connections, but they are wearing a mask and do not feel like they are loved for their true self. This means they are low on their inner sense of relational value.

Given human’s core need to be loved, it is not surprising that loss, rejection, social isolation, and loneliness are all strongly associated with mental pain and depression. What are the implications for depression? It means that to understand one’s depression, one must wonder about the connection between the mental shutdown and failing to be nourished relationally (i.e., dealing with loss, rejection, isolation or loneliness). To deepen your understanding of the human relationship system, it is helpful to understand one’s attachment and interpersonal style.

Attachment refers to the felt sense of bonding, harmony, and security (or its absence) between individuals. When infants are born, they are organized to seek a harmonious and secure relationship with significant caretakers. Basically, they want to know that they are known and valued and will be protected if threatened. If they develop a healthy relational dance with their caretaker, they will feel “secure.” If do not feel this, they will develop an insecure attachment style.

There are three major insecure attachment styles that take shape in adolescents and adults. One style is an “other-oriented, anxious-preoccupied” style that orients the individual to be a bit dependent on others and constantly seeking approval or contact.

A second attachment style is essentially the opposite: a counter dependent, “dismissive” style that downplays relational needs (i.e., if someone says in therapy that they don’t care what other people think or feel about them at all, then they are likely being counter dependent--see here for more). Finally, there is a confused, “fearful-avoidant style”, that trusts neither one’s self, nor others. Folks with insecure attachment styles can find it difficult to build trusting, intimate relationships that are truly nourishing. It is important to know your attachment style. For more information, see here and here is an assessment to give you an idea of where you fall.

Interpersonal style refers to one’s basic tendencies for interacting with others, and it shows up in terms of key personality traits, such as extraversion and agreeableness. When people are forming first impressions, they look for friendly and confident styles of being, and so folks who are low in either extraversion or agreeableness makes it more challenging to develop new relationship connections. Here is a quick, free assessment to get a sense of your level of agreeableness. Attachment and interpersonal styles are often aligned such that there are a number of folks who are agreeable and dependent (other-oriented).

On the flip side, there are others who are both disagreeable and counter dependent/dismissive (self-oriented). Folks who have extreme other-oriented or self-oriented relational styles often experience difficulties getting their needs for relational value and social influence met.

It is also useful to keep in mind that a significant subset of relationship problems stem from being “hypersensitive” or fearful and avoidant in social situations. This refers to a feeling of fear or dread or a massive aversion to conflict or criticism which then causes people to avoid contact. If you think this might describe you, then you should perhaps check out this blog on social anxiety.

Although our focus in this blog series is on the individual and structured from a self-help perspective, it is crucial that we are all aware that our society is structured in a way that has many “cracks” for people to fall through. In an earlier blog in this series, it was noted that depression is virtually unknown in hunter-gatherer societies. We humans are structured to be part of a connected and interdependent band of people that work together on the projects of living. The modern industrial/information age society is much more individual and fractured and fragmented.

It is highly likely that many people are depressed because their core relational needs are going unmet. A recent book by Johann Hari called Lost Connections: Why You Are Depressed and How to Find Hope explores the concept of depression and emphasizes the key is understanding how it emerges from being disconnected. He offers a very engaging and sophisticated look at depression from this perspective and helps people consider ways that they might reconnect with the world in a healthier and more adaptive way. In addition, here are some other books on fostering healthy relationships.

In the world of psychotherapy, there are a host of “interpersonal” approaches to depression. The focus of interpersonal therapy includes helping people overcome problems with: (a) transitions into new roles; (b) grief or loss of old roles; (c) ongoing conflicts and disputes; and (d) lacking skills and dealing with heightened interpersonal sensitivity, like shyness. If you think you need help in understanding your relationship style and the ways that conflicts in a relationship might be central to your state of shutdown, here is a self-help book, called The Interpersonal Solution to Depression.

This blog and the previous one on emotions represents the "mental core" of depression. That is, the "heart" of depression very often centers on relational dynamics and problems of loss, rejection, isolation, and loneliness, coupled with negative emotions that then result in a vicious cycle of problems and ultimate shutdown. The next blog shifts the focus to the "head" and explores ways you can learn to engage in adaptive self-talk.