Dave Cramer has been making ebooks for 15 years, and complaining about ebook standards for nearly as long. He was co-editor of the IDPF specification on fixed-layout ebooks, but in recent years has become heavily involved with the W3C and web standards, editing several specs for the CSS Working Group and writing “Requirements for Latin Text Layout and Pagination” for the Digital Publishing Interest Group. When not doing standards work, Dave writes XSL, works on typesetting with HTML+CSS, hunts for interesting information in mountains of XML files, and skis up and down literal mountains, preferably in Canada. He dreams of bringing the rich history of print design and typography to ebooks and the web. You can see Dave at ebookcraft delivering a talk called The Past, Present, and Future of Digital Publishing That Hasn’t, Isn’t, But May Still Meet the Promise of the Web.

Here we are, in 2019, talking about EPUB 3.2 and web publications and new releases of EPUBCheck and all sorts of exciting things. How did we get here? I thought I’d take a quick walk through the history of EPUB, and answer questions like “Why can’t I use HTML?” and “Why does 9/11 come up so much?”

1999: The birth of OEB

On Sept. 11, 1999, David Ornstein created an ebook as a sample to accompany the very first ebook specification, OEB 1.0. OEB stands for “open ebook,” and the spec was created by the Open Ebook Forum, which eventually became the IDPF. That ebook was pretty simple — a single HTML file and an OPF package file that would look completely familiar to anyone working with EPUB today. But back then there was no packaging, no OCF. Just a folder with some HTML and the package file. You could zip it if you wanted to.

<!DOCTYPE package PUBLIC "+//ISBN 0-9673008-1-9//DTD OEB 1.0 Package//EN" "oebpkg1.dtd">

<package unique-identifier="ident">

<metadata>

<dc-metadata>

<dc:Identifier id="ident" scheme="adhoc">10101010101010101010101011</dc:Identifier>

<dc:Title>Frequently Asked Questions about Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever</dc:Title>

<dc:Creator role="aut" file-as="Ornstein, David">David Ornstein</dc:Creator>

<dc:Creator role="spn">NuvoMedia, Inc.</dc:Creator>

<dc:Rights>Copyright © 1999 David Ornstein. Permission is granted for free

distribution only in complete, unmodified form accompanying the Open eBook Publication Structure Specification.</dc:Rights>

<dc:Description>Ebola is a virus named after a river in Zaire, its first site of discovery. This document provides answers to common questions about Ebola.</dc:Description>

<dc:Publisher>outbreak.org</dc:Publisher>

<dc:Date>1999-09-11</dc:Date>

<dc:Type>FAQ</dc:Type>

<dc:Subject>OEB</dc:Subject>

<dc:Subject>eBook</dc:Subject>

<dc:Subject>Ebola Virus</dc:Subject>

<dc:Source>www.outbreak.org</dc:Source>

<dc:Language>en</dc:Language>

</dc-metadata>

</metadata>

<manifest>

<item id="doc" href="ebola.html" media-type="text/x-oeb1-document" />

</manifest>

<spine>

<itemref idref="doc" />

</spine>

</package>

Nineteen years later, I took that original OEB 1.0 book, put it in a modern OCF container, and made it into an EPUB. It had so many validation errors that I had to give EPUBCheck the rest of the day off. But I was able to open it in Calibre.

2007: EPUB (and some gadgets) change the world

Remember when I said there wasn't a packaging format for ebooks back in 1999? That was remedied on (wait for it) Sept. 11, 2006 with the publication of OCF 1.0. That was the first of the three specs that would form EPUB.

On Sept. 11, 2007, the other two specs were published: OPF 2.0, which covered the package file, and OPS 2.0, which covered the contents of an ebook. Together they were called EPUB 2.0, since it was a successor to OEB 1.2. Confusing numbering will remain a theme in our history.

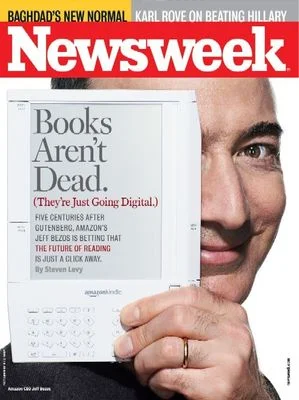

A few months earlier, the iPhone came out. A few months later, the Kindle came out. That was so long ago that Jeff Bezos had hair. And people started buying ebooks — it became big business. Before EPUB, some of us had to make six different versions of every title: OEB, Microsoft LIT, Palm, Sony, Mobipocket, and PDF. *This* was a revolution. We had a standard, implementations, and a market.

EPUB 2.0 wasn't perfect, of course, but it was good enough for a lot of trade publishing.

2011: EPUB 3

After the revolution, change slowed down. EPUB 2.0.1 came out in September 2010. And then work started on a significant revision, EPUB 3.0. Why?

EPUB had always depended on HTML to express content. But a modest revolution was brewing in the HTML world, with the development of HTML5. HTML5 included many more semantic elements — article, section, aside, and, crucially, audio and video. So EPUB 3 moved to HTML5, both for content and the critical navigation document. Perhaps for the first time, EPUB was moving in the direction of the mainstream web.

Also around that time, Apple and others were experimenting with ways to create ebooks out of really complicated books — cookbooks, comics, children's books, college textbooks. They used existing CSS features like absolute positioning, and combined that with metadata that influenced layout. Amazon had a slightly dissimilar idea. Seeing the risk of incompatible formats, the IDPF worked hard to create a new Fixed-Layout (FXL) standard, which could express what both Apple and Amazon had done.

EPUB 3 came out on Oct. 11, 2011. (Why 10/11 instead of 9/11?) The FXL spec came out in March 2012.

But...

No one really started using EPUB 3. First of all, the IDPF had a bad habit of finishing specs before implementations existed. They built it, but no one came.

HTML5 was awesome, but CEOs didn’t care about semantics, and a lot of reading devices were never going to support audio and video. Publishers tried fancy “enhanced” ebooks, but they were hard to make, and never really had a reason to exist. Hachette put out a book where David Baldacci took you on a video tour of his office — it’s gloriously bad. Fixed layout did gain a market, partly because it was possible to create FXL in a semi-automated fashion. It wasn't polite to point out that the books were mostly smaller than the print editions they mimicked, and thus hard to read.

And, as I said, EPUB 2 was “good enough” for lots of people. There were lots of old ebook devices out there that were never updated. After three or four years, most big publishers started using EPUB 3, but it was still designed to be backwards-compatible with EPUB 2. We don’t do anything fancy. Nothing ever changes.

Now it’s seven years after EPUB 3. There are still publishers creating EPUB 2, and it's so bad that BISG is writing an open letter to the publishing community urging laggards to move to EPUB 3.

2016 to 2019: EPUB 3.1, EPUB 3.2, and the rise of the community group

Meanwhile, we still wanted to improve EPUB 3. The goal for EPUB 3.1 was to make a simpler, cleaner, and better EPUB. We wanted better alignment with web standards. We wanted a more readable specification. We wanted to get rid of some obsolete features that conflicted with web standards.

We were, in fact, ambitious. We wanted to bring EPUB into the mainstream of the web by allowing HTML5 as well as XHTML5. We wanted “exploded” EPUBs that weren’t packaged (known as “BFF” or “Browser-Friendly Format”) so they would work on web servers. We wanted to get rid of the ncx for good.

But not everyone agreed.

Reading systems didn’t like the idea of using HTML, because some of them processed EPUB using XML tools. The browser-friendly format seemed too big a step for 3.1, and perhaps was more naturally a goal for the W3C’s new Digital Publishing Interest Group. Everyone worried about old reading systems that depended on the ncx.

Worst of all, EPUBCheck, the validation tool for EPUB, was in trouble. It had always depended on volunteer developers, but the well had run dry. And the entire EPUB ecosystem depends heavily on formal validation — most retailers won't even process an EPUB that hasn’t passed EPUBCheck. So if EPUBCheck didn’t support EPUB 3.1, literally no one would use it. And that’s exactly what happened. EPUB 3.1 was finalized just as the IDPF merged with W3C, but it didn’t matter.

After the merger, responsibility for EPUB maintenance fell to the new EPUB 3 Community Group.

Garth Conboy and Makoto Murata proposed that we roll back EPUB 3.1, and focus on an update that was focused on backward compatibility. Even the name proved controversial, as some wanted EPUB 3.0.2. But we couldn’t just pretend that EPUB 3.1 never happened.

The main idea was to keep the good stuff from 3.1 — the evergreen relationship with HTML and CSS, the better spec organization — but roll back things that affect compatibility. The idea is that every EPUB 3.0.1 file is already valid EPUB 3.2, even if it doesn’t know it.

We have done that — work is largely complete in the community group. We've even documented all the changes since EPUB 3.0.1. Best of all, EPUBCheck should support EPUB 3.2, thanks to a fundraising effort spearheaded by some folks you’ll meet at ebookcraft. But we still need contributions — please encourage your organization to donate.

2019 and beyond: What next?

What might happen next? Will there be an EPUB 3.5? EPUB 4? What will happen with web publications? Come to ebookcraft and find out!

If you'd like to hear more from Dave Cramer and the future of the ebook, register for ebookcraft on March 18 and 19, 2019 in Toronto. You can find more details about the conference here, or sign up for the mailing list to get all of the conference updates.