Sport and Competition

Near the Knuckle

Understanding bare-knuckle fighting as a biologist

Posted April 29, 2019

“If you can’t take pain you can’t be a real fighter”

(Bartley Gorman. Bare-Knuckle Fighter. Once known as “The King of the Gypsies”)(1)

I’ve just got back from the EHBEA (European Human Behaviour and Evolution) conference in Toulouse, where I presented a paper on Traveller bare-knuckle fights. As usual at such events, I was surrounded by anthropologists (far more intrepid than me) who go off to exotic parts of the world, to document exciting, and sometimes dangerous, human behaviors.

One of the grand-daddies of all the anthropologists was the renowned Napoleon Chagnon. (2) When, in the 1960s, he arrived to make the first contact with the Yanomamo—a remote group in the Amazon-- he was bewildered by a complex, noisy and violent spectacle. At the center of it, two men went from hitting each other with fists, which then escalated to bashing each other over the head with long sticks, and finally to wielding axes (albeit the blunt sides) on each other.

Immortalized as “The Ax Fight”, Chagnon analyzed this confusing spectacle and broke it down into manageable pieces. Far from being a chaotic free-for-all, he showed the exchange to be a richly complex, and highly social, escalation of insult, and hierarchical defense. This particular exchange only ended when one protagonist went a bit too far, using potentially lethal force, at which point the headman stepped in.

I lack Nap Chagnon’s intrepid nature, but admire his methods and willingness to use the insights of biology to understand human behavior. I can’t go to the Amazon basin, but what I do have on my doorstep is the phenomenon of Traveller bare-knuckle fights. While not strictly legal in Ireland, they are somewhat tolerated by the authorities. Often there is a call out (these days on Youtube) and two men will meet to settle some matter with bare fists. Here is a brief example of one such.

The Logic of Male-Male Competition

How best to understand such interactions? We psychologists tend to be a fairly soft-living bunch, and we get spooked at violence, typically labeling it as “anti-social” in textbooks. The dominant theory in the social psychology field is that the immediate cause of aggression is frustration, and its transfer to other targets. Sometimes a model of social learning is applied to this so that children learn to be “anti-social” from role models. A brief reflection shows the tension here in the theory. Social learning results in anti-social behavior? Something has to give. The word “social” is doing too much (and contradictory) work.

A biological perspective adds depth, by pointing out that a lot of violence—though by no means all—can be understood through understanding the highly social logic of male-male competition. I’ve explored this in detail elsewhere, but the brief idea here is that males often compete for status, because status equates to mating opportunities (which is not quite the same thing as being attractive per se). The catch is that even a weaker challenger in such a contest could hurt the eventual winner if they fight to the death. Thus, it benefits both of us (or, rather, the underlying genes coding for such behavior) to have a limited competition, which decides (all other things being equal) who would have won in a fight to the death, without our actually having to go this far.

All across nature, we find males engaging in such contests, often using specialized weapons like antlers, or levers to upend each other. (3) Injury is likely, death is a possibility, but usually—like Bartley Gorman said--these contests can be settled by a credible display of who can take and dish out the most pain.

Humans don’t have antlers, or long prongs on their fronts to tip each other over. Instead, we have extended phenotypes of ritual competitions, duels, and fights. It wasn’t long ago that men in our culture were expected to be able to defend their honor with blades. The last saber duel was fought in Europe in the 1950s, and I tell that story here. But even though we have replaced such interactions with the rule of law…mostly…pockets of males defending their honor with their own mettle still remain. Sport is one field. But another is bare-knuckle fighting.

The Gentle Sex?

Something worth adding at this point is that humans are a mutually sexually selecting species. Much female-female competition is reputational in nature (and thus gets missed by many male researchers). But females of our species can also compete with physical one-on-ones. How often do they do this when compared to males? A first pass at looking at the difference might note that BoxRec, a good record of the professional boxers in the UK, has nearly 22000 entries for male fighters, and 1500 for female ones. It’s possible that this 15:1 difference is just sexism rather than a difference in interest, but in other sporting areas where women have been traditionally excluded, such interest shows.

For example, women were banned from competing in marathons until 1972. Does this historical injustice show in a comparable way in terms of current interest? Not especially. The Boston Marathon (a reasonably representative one) now fields about 20,000 men and about 10,000 women per year. There are still more men—twice as many—but not 15 times as many. Katie Taylor, a prominent Irish boxing world champion, is not unusual when she complains that there are not enough female competitors for her to prove herself against. No female marathon runner would voice a similar complaint.

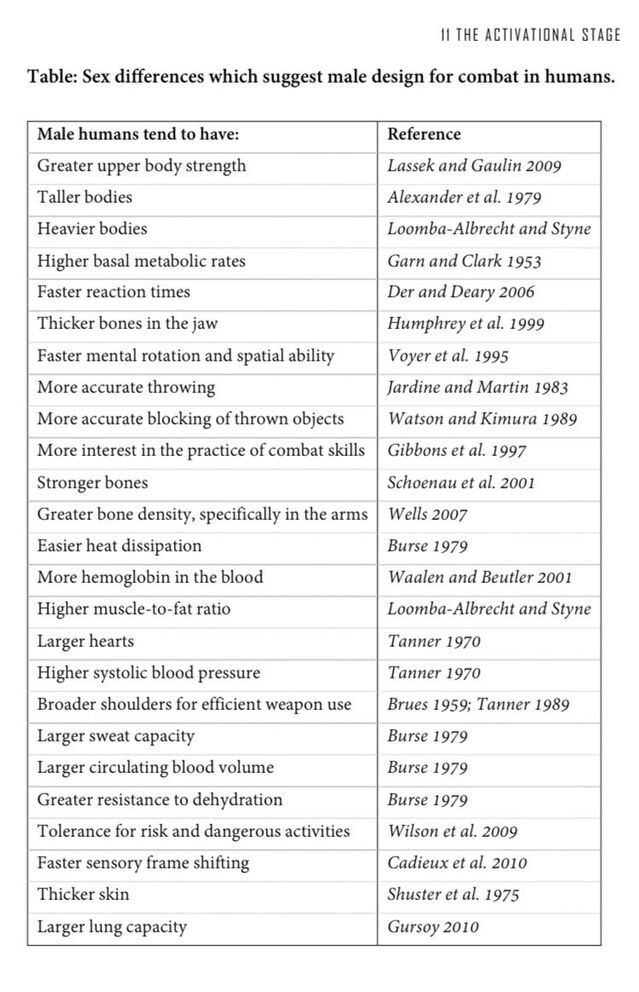

These average differences in average interest between the sexes in different sports are reflected in differences in body composition. Humans only differ between the sexes by about 10% in terms of mass, but in terms of average muscle mass, they differ by over 60%. Fewer than 1% of women have the grip strength of the average man. (5) The Katie Taylors exist of course (I’d be the last to dare suggest otherwise!), but they are likely to be rarer because those fields are much less the focus of female-female competition. The thought occurs—we might even use the level of these discrepancies as a measure of the differences in selection pressure between the sexes on these grounds?

Whatever the truth of that, what happened when we analyzed Traveller bare-knuckle fights? We got videos of the fights in question and showed them, in a controlled form, to people who knew about fighting (boxers, and mixed martial artists of both sexes) but who did not know what theories we were testing. A number of possibilities were available.

Were the fighters showing off to females? If so—we would expect to see women present, which we never witnessed. Were bullies who were upsetting the group dynamics being pulled down to everyone else’s level? On the contrary, fights were typically between single fighters of roughly equal size, age, status, and ability. Were the fights chaotic free-for-alls, arising spontaneously through frustration? Not at all. They were refereed, ritualized, and there were frequent interventions to re-assure the fighters that they had “done enough” (to show their mettle) and that honor was therefore satisfied. Fouling could happen, but it typically resulted in social sanction, and it was pretty rare. When it did occur, it could seem deliberate, perhaps to avoid an otherwise inevitable loss.

Also, it’s worth noting that “bare-knuckle” can be something of a misnomer. Often fighters wore hand-wraps—not to protect the knuckles, but to stop the ligaments between the delicate metacarpal bones from tearing on impact, which can result (in extreme cases) in someone losing a hand. This was itself a pleasing confirmation of a paper I had out in the Journal of Experimental Biology back in 2013, that argued that--however it may appear from protruding knuckles--human hands were adapted to holding, not hitting. Slowed-down video shows experienced fighters impacting with the edge or the heel of the hand, in preference to the knuckles as well. (6)

In short, these contests were—just like Chagnon found with the Ax-fight--ritualized, organized, and highly socially significant affairs which can be understood—at least in principle—using the methods and theoretical approaches of biology. That’s the pilot study out of the way, and what we’d like to do now is look in more detail at surrounding behaviors and consequences.

References

1) “Traveller” is the preferred term today, “gypsy” being often seen as somewhat insulting. However, it would be anachronous and patronising to force this update retrospectively. Gorman referred to himself this way, and all references to him in literature and film are to “gypsy” rather than “traveller”. However, the rest of this post will use the preferred modern term. Note that “Traveller” is the preferred Irish spelling.

Gorman, B., & Walsh, P. (2002). King of the Gypsies. Milo Books.

Update 21/05/2020: I just learned that Bartley Gorman is Tyson Fury's uncle. So much for genetics, eh?

2) Chagnon, N. A., & Bugos, P. (1979). Kin selection and conflict: An analysis of a Yanomamö ax fight. Evolutionary biology and human social behavior: An anthropological perspective, 213-238.

3) Smith, J. M., & Price, G. R. (1973). The logic of animal conflict. Nature, 246(5427), 15.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/hive-mind/201803/bare-branche…

https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/hive-mind/201710/mass-killing…

https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/hive-mind/201612/the-last-duel

4) For frustration/aggression and social levelling hypotheses see

Dollard, J., Doob, L., Miller, N., Mowrer, O., & Sears, R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Zillman, D. (1971). Excitation transfer in communication-mediated aggressive behaviour. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 419-434.

Boehm, C. (2000). Conflict and the evolution of social control. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(1-2), 79-101.

5) Wells, J. C. (2007). Sexual dimorphism of body composition. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism, 21(3), 415-430.

https://mmajunkie.com/2014/10/woman-vs-man-in-a-bare-knuckle-no-rules-f…

6) King, R. (2013). Fists of furry: at what point did human fists part company with the rest of the hominid lineage?. Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(12), 2361-2361.

http://jeb.biologists.org/content/216/12/2361.short

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4729335/

King, R. & O’Riordan, C. Near the knuckle: Bare knuckle fights in Irish traveller populations. In press for Human Nature 2019.

Available online first at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12110-019-09351-7?wt_mc=Inte…

Nisbett, R. E., & Cohen, D. (1996). Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the South. Boulder: Westview Press.

Paper out in Human Nature available online at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12110-019-09351-7?fbclid=IwA…