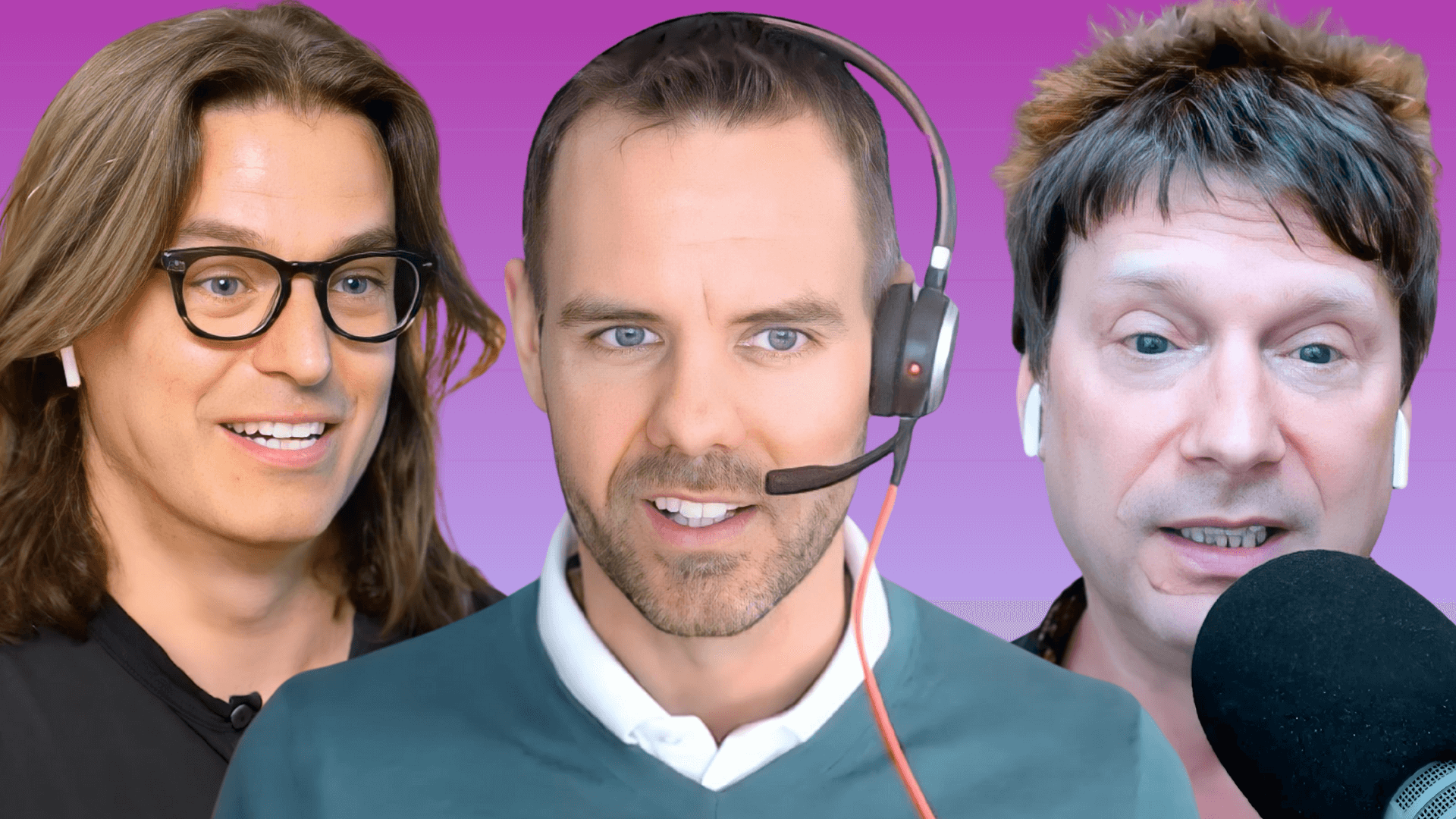

Paul Gilmartin (@mentalpod) is the host and producer of The Mental Illness Happy Hour Podcast, known for his brutal honesty, authenticity, and transparency.

The Cheat Sheet:

- How addiction works as a frame of mind and what a support group offers an addict on the road to recovery.

- Why shaming ourselves into becoming better people is a terrible strategy for self improvement.

- Why someone living a seemingly successful life envied by others might have suicidal thoughts multiple times a day.

- The ripple effect a traumatic childhood can have on an adult and what can be done to move on.

- The role of social intelligence and a code of ethics — a principled life — for guiding behavior.

- And so much more…

[aoc-subscribe]

Download Episode Worksheet Here

You may recognize comedian Paul Gilmartin from his run as co-host on TBS’ Dinner and a Movie from 1995 to 2011. Since 2011, he’s been the host and producer of The Mental Illness Happy Hour Podcast.

Paul rejoins us (catch his first appearance on the show here) to explain how he stopped letting fear guide his actions, how he’s learned to ask for help from others, what myths he’s dispelled in the process, and what it means to live a principled life.

Listen, learn, and enjoy!

More About This Show

“Left to my own devices, I don’t know how to do five,” says The Mental Illness Happy Hour Podcast host Paul Gilmartin. “I do one or I do ten. I could give you instances after instances of where I find that I like something and I run the wheels of it. It’s just how I’m wired — it’s how addicts are wired.”

Addiction expresses itself in many varieties, but at its core is this common wiring that compels the addict to act — often at odds with his or her well-being. After years of coping with addiction related to workaholism and alcohol abuse that led to deep depression and daily thoughts of suicide, Paul found support groups especially effective in keeping addiction at bay.

“I came to find out that my view of the world was based so much in self that I wasn’t experiencing real human connection,” Paul says. “I was dealing with everything as if I was working an angle to always get what I wanted. But I was never putting myself in other people’s shoes and thinking, ‘What is it like to experience me? What might this person want? How might I help this person?’ Because I’d always thought that to help you was to take away from me unless it obviously benefited me — and that’s one of the biggest myths that degrades people’s lives not only mentally but emotionally and spiritually.”

While some decry 12-step programs and support groups as a kind of religion, Paul disagrees.

“They may talk about a higher power…but it’s really the principles of being a good person that you’re trying to connect to,” says Paul.

To Paul, this higher power could be anything from the sun to the ocean to money to sex — it’s whatever inspires someone to get up in the morning. And when we don’t have something driving us, we fall into habits of addiction and risk losing the very will to live. Learning how to balance these tendencies is the challenge.

Paul sees spirituality — for him, living a principled life — as a muscle. If he doesn’t attend a support group (akin to a gym for him), he’ll start slacking off and doing things he’s not proud of.

“Left to my own devices, I will sit in my recliner and watch Netflix and cut corners and not let people in — and not help people. That’s been the other part that has been so good for my self-esteem and has brought me so much peace — somebody else coming in to a support group and giving them my phone number and saying, ‘Hey, let’s go have coffee tomorrow! You seem like you’re in a tough spot.’ And just talking with them. Sometimes giving them advice, sometimes sharing my own story.”

The principled life for which Paul strives comes from a place not driven by fear and ego, but meaning and purpose beyond self-aggrandizement. Long-time listeners to this show might remember Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success author Jessica Tracy addressing this very thing when she outlined the differences between authentic pride and hubristic pride in episode 596.

Finding Help

Coming from a childhood and background that wasn’t particularly supportive, Paul had to learn the value of a support group over time.

“There’s no one particular way, but I can tell you this: trying to do it by yourself is like trying to give yourself a haircut or see the back of your head. You need other people to do it.”

Rather than seeing the need to ask for help as a sign of weakness, Paul says we should think of it as calling for reinforcements during a fevered battle: it’s a smart strategy. But he concedes it’s not easy to take this first step; he was more willing to put a gun in his mouth, about to take his own life, than ask for help.

“But because I had to do that, I’ve learned the benefits of [asking for help]. Today, I don’t mind doing it,” says Paul.

Healthy vs. Unhealthy Expression

Nowadays, Paul sees these as the things in his life he can’t live without: vulnerability, connection, honesty, and a boundary of not allowing toxic people into his life.

“Having done the podcast for six years, one of the biggest things I see that destroys people’s lives is not understanding the difference between healthy and unhealthy ways of expression emotion,” says Paul.

Before support groups became a regular part of Paul’s life, he couldn’t even identify what he was feeling. He’d numb himself with alcohol and porn, which not only prevented him from understanding his own feelings, but put a barrier between himself and others. When he stopped relying on this overall numbness, he was better able to identify and filter out the toxic people in his life.

“When you’re at peace, it’s much easier to make a principled decision. When you’re in fear, that’s when it’s hard to make a principled decision,” says Paul.

The Ripple Effect

While Paul didn’t have what most would consider an ideal childhood, he doesn’t blame his parents for making him into an addict — which he sees as more of a genetic predisposition.

“That being said, I grew up where healthy coping mechanisms weren’t modeled for me. They weren’t modeled for my parents, either,” Paul says. “So in the absence of that, we’re going to do what we see other people doing — which for my mom was manipulating people…and with my dad, I saw somebody who was isolated at the end of the couch. I didn’t know how to ask for help. I didn’t know how to open up to people. I just knew that, if I wanted people to like me, I had to be who I thought they needed me to be.

“Instead of saying, ‘I’m going to be my authentic self and they can take it or leave it,’ I was decades away from even knowing what my authentic self is. And I’m still discovering what my authentic self is!”

It wasn’t until much later in life that Paul realized the ripple effect his parents’ behavior had on him, which made connecting with others all the more difficult — not uncommon among survivors of childhood trauma and neglect.

“One of the things that survivors struggle with is leading a socially and professionally anorexic life. We stay small because it’s what we know and we have trouble asking for help or trusting.”

But what he’s come to realize — again, though help from support groups — is that nobody’s problem is so unique that it’s beyond sharing with someone else who will understand.

Who Are You Calling Lazy?

“I don’t know, some days, if I’m being lazy or if I’m leading a balanced life,” says Paul. “So I have to talk to friends about it…my default is to pull away for fear of failure. But I also have to be on guard that I’m not trying to push myself into being somebody that isn’t authentic to who I am. It’s hard to know.”

So how do we put ourselves on guard to know the difference? Paul says we should constantly be trying new things. “If it feels like it doesn’t work for you, maybe ask yourself, ‘What is it about this that isn’t working for me?’ And then maybe you’ll have your answer as to whether or not it feels authentic.”

Do I Have Control?

These are the questions Paul asks himself whenever he’s confronted with a situation that prompts an emotional response:

Is this anything I have control over? If it isn’t (for example: rush hour traffic), he surrenders to it.

If I do have control over this, what is the ethical or principled thing to do here? “The answer is usually very apparent, but sometimes it’s an answer that sends fear into my brain — like fear of, ‘Oh, you’re going to have to talk to somebody,’ or, ‘You might have to drive across town and give somebody a ride.'”

Paul cautions that we need to be sure we’re acting on what we really believe is the right thing and not just trying to appease someone into not being angry with us.

In consciously trying to live a principled life, Paul takes things a lot less personally — because he realizes that other people are just as flawed as he is, and therefore as worthy of forgiveness. So while he might feel a quick flash of anger if he’s cut off in traffic, he no longer chases down the transgressor to engage in physical confrontation. If he’s playing hockey and the ref makes what he thinks is a bad call, he might explain he saw things differently, but no longer offers to buy the ref a new pair of glasses.

THANKS, PAUL GILMARTIN!

If you enjoyed this session with Paul Gilmartin, let him know by clicking on the link below and sending him a quick shout out at Twitter:

Click here to thank Paul Gilmartin at Twitter!

Resources from This Episode:

- Episode 289: Paul’s last appearance on this show

- The Mental Illness Happy Hour Podcast

- Paul Gilmartin at Facebook

- Paul Gilmartin at Instagram

- Paul Gilmartin at Twitter

- A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose by Eckhart Tolle

- Jessica Tracy | Take Pride (Episode 596)

- Paul’s resources for finding help

You’ll Also Like:

- The Art of Charm Challenge (click here or text AOC to 38470 in the US)

- The Art of Charm Bootcamps

- Elite Human Dynamics

- Best of The Art of Charm Podcast

- The Art of Charm Toolbox

- The Art of Charm Toolbox for Women

- Find out more about the team who makes The Art of Charm podcast here!

- Follow The Art of Charm on social media: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook

On your phone? Click here to write us a well-deserved iTunes review and help us outrank the riffraff!