If it hadn’t been for the pandemic and the near impossibility of visiting Vivian Stephens in person, I’m not sure I would have been so attuned to her voice. It is gay and mellifluous; she always sounded delighted to hear from me, a reaction most reporters are not accustomed to. But there was something else: she answers questions about herself not in sentences or paragraphs but in pages, and sometimes even chapters, as if she’s been keeping the whole story of her life in her head, just waiting for someone to ask about it.

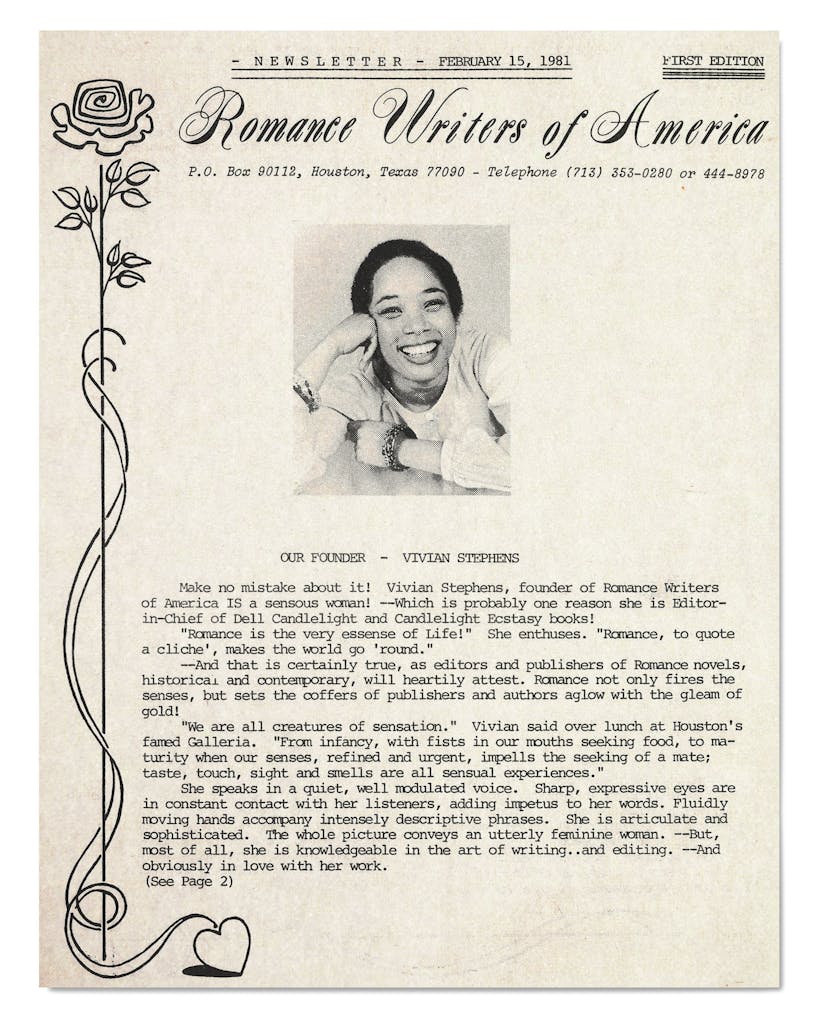

That voice matches an official photograph from her earlier days, when she was a star editor of romance novels at Dell, then a division of Doubleday, in New York. She was uncontestably beautiful, with a broad, toothy smile and a sly intelligence behind her eyes, a spray of freckles over her cheeks, and an Afro that, befitting the publishing world, was neither too corporately short nor too aggressively political. She is propped up on one elbow and leaning in toward the camera. She looks game for anything.

Stephens is 87 now, under self-imposed lockdown in one of those amenity-rich mid-rise apartment complexes that have sprouted all over Houston, this one just north of Hermann Park, in the Binz area. Her one-bedroom unit is cluttered with papers and stacks of books on nearly every surface. There are many romance novels, yes, as well as more-cerebral tomes such as A Nervous Splendor, a history of Vienna in the late 1880s. Family photographs, some dating back almost to that time, populate a small table in a living room corner.

The most captivating photo, though, is the black-and-white one Stephens has pushpinned to the wall above her computer. Taken in 1964, it shows her poised on the steps of New York’s Lincoln Center wearing a sleeveless sheath dress, hands on her hips, ready to take on the world. Even now, she is vibrant and active. She spends her days talking with friends all over the country. She looks forward to her 83-year-old sister Christina’s daily phone check-in (“Yes, I’m still here”), fixes vegan meals from scratch, meditates, coaches a few long-distance writing clients, watches televangelist Joel Osteen, thinks through that memoir she still intends to produce, makes notes on novels she hopes to write, and surfs the web for information on aging and nutrition for her blog. “Aging is the next great adventure,” she told me with an almost evangelical certitude.

But I was calling about the past, not the future. Specifically, an email she had received in May from Alyssa Day, the president of the Romance Writers of America, an organization based in northwest Houston, not too far from the white and wealthy exurb of Champions. Stephens had been instrumental in founding that group back in 1980.

What is this? Stephens thought to herself when she saw the email, which asked, politely and respectfully, if it would be okay to name the RWA’s highest writing award after her because her “trailblazing efforts created a more inclusive publishing landscape and helped bring romance novels to the masses,” as the press release would later put it.

Well, this is interesting, was Stephens’s next thought.

She wouldn’t put it this way, but it was kind of like getting an email from an old boyfriend who was now trying to make amends. It wasn’t that there was bad blood between Stephens and the RWA—she’d never admit to that, anyway—but there was some hurt that dated back to when she had felt disappeared by the organization.

The timing of Day’s email wasn’t incidental. The RWA had been embroiled in a bitter, and at times very public, racism scandal for much of the previous year. A skeptic might suggest that, good intentions aside—and there were good intentions—the Vivian award could be viewed as just another way to sanitize prior bad behavior on the part of the RWA. Stephens had to decide—again—whether to let bygones be bygones after a forty-year relationship that had been, in its way, a romance, albeit a difficult one.

So Stephens was uncharacteristically ambivalent about the RWA’s offer. After some thought, however, she wrote back to say that she would be honored. And then, being Vivian Stephens, she couldn’t resist adding a metaphorical flourish to the statement they requested. She cited an astrophysicist who explained that as stars explode, they produce the magical, mystical remnant that is stardust. “Since we all live in the universe it is well worth remembering that underneath the outer dressing of ethnicity, color and gender, we are all the same,” she wrote. “Showered with the gift of stars.”

Then she hit send.

Romance writing has always been easy to laugh at, at least for the uninformed. You might imagine that these stories mostly involve a castle on the Scottish Highlands, inhabited by a restless warrior wearing nothing under his kilt. Or maybe you picture the broad and bare-chested phenom Fabio, taking time out from piloting his Viking ship on the high seas to attend to a buxom and bound captive down below.

But if this is your vision of the romance-writing world, you might have missed its evolution into a billion-dollar-a-year business. In 2016 romance made up 23 percent of the overall U.S. fiction market, and the net worth of some of its writers exceeds that of John Grisham (see Nora Roberts and Danielle Steel). According to Christine Larson, a romance expert and journalism professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, 45 percent of the romance writers she surveyed made enough to support themselves without a day job—“that is shocking for any group of writers,” she said—and thanks mainly to their embrace of digital publishing, 17 percent make more than $100,000 a year. Not Mark Zuckerberg money, but far more than the $45,000 median income of American working women.

That legitimacy is due in many ways to the vast social changes of the past several decades. Once upon a time, many romance writers—and their readers—were middle-aged, white stay-at-home moms who got their hair done in beauty parlors. But those women, who were often looking for relief from the doldrums of vacuuming and child-rearing, were more recently joined in the field by trial lawyers and anthropologists and social workers—professional women of all races and creeds—who were themselves looking for a creative outlet away from the pressures of family and career.

As more women joined the workforce, earned their own money, put off marriage (or dumped their loser husbands), and got on the Pill, a different kind of romance writer emerged, one less interested in emotional, sexual, and financial rescue than in self-respect and free will. The books they wrote reflected their world, even if writers set their works in Victorian England or the antebellum South. “If you look at romance now, it’s very much reflective of the current moment,” said Steve Ammidown, an archivist at Bowling Green State University’s Browne Popular Culture Library, which houses an enormous romance collection, including many papers from the RWA and more than forty romance authors.

Whatever controversies are being sorted out in the larger world have also been grappled with in romance novels, sometimes even before the larger world knew what was coming. “The RWA is a microcosm,” said the romance writer LaQuette, one of many who voiced this opinion.

Today, romance novels involve just about any combination of protagonists imaginable. There are books for every color of the human rainbow, every ethnicity and sexual orientation, every religious affiliation—and not just Jewish or Muslim, but Amish too. There are erotic romances for those who are gay, straight, and transgender. There are paranormal romances. Cowboy romances. Romances between humans and space aliens. Romances for those with autism.

Romance is a whole industry, with its own academicians, like Laura Vivanco (Pursuing Happiness: Reading American Romance as Political Fiction), and its alternative historians, as evidenced by Maya Rodale’s Dangerous Books for Girls: The Bad Reputation of Romance Novels Explained. There are influential blogs with names like Smart Bitches, Trashy Books and popular podcasts like Fated Mates, which, according to its Apple Podcasts description, “highlight[s] the romance novel as a powerful tool in fighting patriarchy . . . with absolutely no kink shaming.”

No one knows better than Stephens that the issues that threatened to destroy the RWA go all the way back to its beginning.

Despite all the changes, the foundation of romance writing remains the same, perpetuating the fantasy that women can find true love, at least for a while (if not an HEA—Happily Ever After, in Romancespeak—then an HFN, Happy for Now). “This type of narrative, by women for women, is the only space where women can seek joy and triumph on the page,” explained Rodale. “We don’t get these stories from Hollywood; they are not in the news; we don’t get them in literary fiction. In literary fiction women have sex and die. In romance they have good sex and live happily ever after.”

Of course, the inhabitants of Romancelandia, as they call their imaginary homeland, still suffer plenty of contempt at the hands of outsiders. The source of this contempt, they say, is that (1) women are still not taken seriously by men and, often, one another; (2) women writers are not taken as seriously as men writers; (3) women who write expressly about romance are not taken seriously unless they’re named Jane Austen; and (4) women who write about sex are really not taken seriously, because that would be way too scary for a lot of men and women.

Those backward ideas help explain why, when a public scandal rocked the RWA late last year, major news outlets were only too happy to cover the story. “Racism Dispute Roils Romance Writers Group,” declared the New York Times. The feminist website Jezebel weighed in with “Inside the Spectacular Implosion at the Romance Writers of America.” The Houston Chronicle: “As racism scandal escalates, Romance Writers of America board president resigns.” Vox: “The influential trade organization Romance Writers of America is tangled in a web of racism accusations, power grabs, and shadow plots.”

But this news wasn’t really news. It has long been an open secret—certainly among women of color—that romance publishing has a race problem. A 2014 survey of four thousand romance writers conducted by Larson revealed that authors of color earned about 60 percent less than white writers. In 2019, research conducted by the Ripped Bodice, in Los Angeles, one of the few bookstores in America to sell romance exclusively, revealed that only 8 percent of leading romance publishers had released novels by women of color. And, not incidentally or coincidentally, the membership of the RWA is 86 percent white, according to the latest data. No Black writer had won a RITA—formerly the RWA’s highest honor—until 2019, and not for want of trying.

Of course, it has also long been an open secret that publishing in general has a race problem. A 2019 diversity survey found that the industry—publishing companies, book reviewers, agents—is 76 percent non-Latino white (compared with 60 percent of the total U.S. population). The self-examination that started years ago with young adult fiction has spread, after the killing of George Floyd in May, to far more esoteric and elitist groups like the Poetry Foundation and the National Book Critics Circle. Over the summer, some concrete changes occurred, with the appointment of two women of color, Dana Canedy and Lisa Lucas, to head the major publishing houses Simon & Schuster and Pantheon Books.

But by that time, the romance industry had already had its own reckoning—several, in fact. This spring, the RWA emerged from the ashes of its 2019 scandal with a new board dedicated to diversity and inclusivity and righting the wrongs of the past. Shortly thereafter, the email arrived in Vivian Stephens’s in-box.

The promise of transformative change leaves Stephens understandably dubious. No one knows better than she that the issues that threatened to destroy the RWA go all the way back to its beginning.

The RWA’s first newsletter, dated February 15, 1981, hangs yellowed with age in a frame on the wall of the organization’s headquarters, in a converted pine-shaded house not too far from several cushy housing developments that boast “Forest” or “Woods” as surnames. The newsletter features Stephens’s official Dell photo. “Make no mistake about it! Vivian Stephens, founder of Romance Writers of America IS a sensuous woman!—Which is probably one reason she is Editor in Chief of Dell Candlelight and Candlelight Ecstasy books!”

There are several interesting things about this newsletter, not the least of which is Stephens’s confession that she loves “to lie in the warm sun and watch men with firm, muscular bodies come dripping from the sea.” But the most interesting thing is that, when you start delving into the history of the RWA, Stephens gets forgotten pretty quickly. She is remembered in some articles as the Black woman who was a founder of the organization, but then, in many accounts, she disappears. When the controversy erupted within the RWA last year, it was often mentioned, ironically, that the organization had been founded by a Black woman, as if that made the racial clash doubly hard to understand. But Stephens was never quoted in the articles, maybe because some people had heard that she didn’t like to talk about the RWA and so didn’t call, or because they didn’t know where she was or if, indeed, she was even alive. This sort of erasure is something Stephens has dealt with for as long as she can remember.

“I grew up under apartheid,” she told me matter-of-factly when we first spoke. She grew up not just in Houston but in the city’s storied Fifth Ward, a thriving Black community just northeast of downtown, across Buffalo Bayou. Before desegregation and the construction of freeways that sliced up the neighborhood during the fifties and sixties, the Fifth Ward was filled with thriving Black-owned businesses: doctor’s offices and funeral homes, movie theaters and restaurants. Club Matinee was the Cotton Club of the South. Phillis Wheatley High School was one of the largest Black high schools in the country. The Fifth Ward produced, among many others, boxer-entrepreneur George Foreman, the late U.S. congressman Mickey Leland, and Ruth Simmons, the former president of Brown University and the current president of Prairie View A&M University.

Outside the neighborhood, things were different, of course. Houston’s Black population often found work in white communities as nursemaids, housekeepers, cooks, and gardeners. That proximity rarely led to meaningful interactions. “White people hire Black people to raise their children—wouldn’t you think they would pay attention to who that person is?” Stephens once asked a friend. “No,” the friend replied, “because you are invisible. White people don’t see you.”

Stephens’s earliest years were spent in one of the country’s first public housing projects for Black families, Kelly Court, a sprawl of low-rise brick buildings. Soon after World War II, though, Stephens’s father, Adolphus, who worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad, bought a small frame house built by his brother that still stands on Providence Street. Her mother, Oveta, had defied the odds and finished junior college and, more than anything, wanted to be a homemaker for her five children, four girls and a boy.

Stephens describes her upbringing as “structured.” She and her siblings took art and music classes, belonged to community organizations, and went to church and Sunday school. And she read like crazy, competing with her best friend to finish the most books: Little Women, the Nancy Drew series—required reading for any curious, ambitious girl for decades—and Zane Grey’s westerns. “I still remember The Trail of the Lonesome Pine,” she recalled wistfully. (Amazon describes John Fox Jr.’s story this way: “Little June Tolliver changes her life forever the day she hides behind the big Lonesome Pine to observe a handsome visitor. That man, Jack Hale, becomes her champion as he transforms her from a backwater Appalachian waif to a high-society lady.”) She took ballet, and she listened to live radio broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera with her family on Saturdays. There were white-gloved teas and music recitals too. “The images many have of Black people is not the class I grew up in,” Stephens said. “That life is never portrayed on TV. Whenever we see Black people on television, it’s somebody else’s idea of what Black people were like.”

The only time the young Stephens saw white people was when she went downtown to a movie or concert, where she sat in the small balcony reserved for Black patrons, or when she went shopping with her mother. One day, she was proudly dressed in her Sunday best, with her hair curled in Shirley Temple ringlets, while visiting a downtown department store. Stephens was light-skinned like her mother, and she passed a white child who was confused at the sight of her. “Mommy, is that a nigger?” she heard the little girl ask. (Later, when Stephens truly began to interact with white people for the first time, after graduating from a historically Black college, she was bewildered. “It was my greatest disappointment,” Stephens told me, her voice infused with the wonder of that time. “I thought white people were so smart, that they must have had something so wonderful, because it was kept from us. And then I started working with white people, and I thought, Is this it?”)

On the occasional Sunday, her family would go on drives through fancy white neighborhoods like River Oaks. “You knew someone who had a relative who worked in those houses,” Stephens said. “You knew what the food was like, what the dishes were like, and what the clothes were like. You always knew what the good stuff was.”

When Stephens was seventeen, her speech teacher asked her to partner with a promising fourteen-year-old debate prodigy: Barbara Jordan. Stephens had taken elocution lessons and was a mezzo-soprano in the glee club, but Jordan, she said, “had that X factor. Sometimes kids stand out, and she stood out.”

But in some ways, Jordan—who would become the first Black congresswoman elected in a Southern state—was just another Fifth Ward kid. “All of the Black kids in my era and my neighborhood were raised to be excellent in everything they did. It was expected that you would finish high school. In my family it was expected that you would go to college,” Stephens told me. And she did. After becoming the student body president and valedictorian of Wheatley High, she graduated from Texas Southern University in 1955.

After graduation, she headed to Los Angeles to make her way in the fashion industry. The racism in Houston, she felt, would prevent her from finding any kind of job with real advancement. “I had an exit interview with my father and mother,” Stephens said. Her father urged caution when making new friends. “You don’t have to let everybody in your life,” he told her. He also told her to enjoy herself but to know too that she could always come home.

Her mother had different advice: “No, no, no, you must press on,” she told Stephens. “You must have goals.”

There is an inadvertently funny clip of Stephens being interviewed by Ted Koppel on his Nightline news show in 1983. The title of the episode, which was devoted to romance writing, was “Appealing or Appalling?” and Koppel—who that year also covered such topics as the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, the machinations leading up to the 1984 Reagan-Mondale presidential election, and Klaus Barbie, the Nazi gestapo chief of Lyon—seemed incapable of fathoming why women were spending almost half a billion dollars a year on escape reading about romance and sex. It fell to his guests, top-selling romance writer Janet Dailey and Stephens, then the editorial director of Harlequin Books’ new American romance division, to try to explain this shocking, maybe even subversive trend.

For the occasion, Stephens wore a white dress with lace-trimmed puffed shoulders as well as a string of pearls and matching pearl earrings. She managed to look both feminine and authoritative. Stephens rarely stopped smiling, but she also displayed the manner of a high school teacher trying to coax something smart out of a student who didn’t think the subject matter was important. (“Reporters never knew what to ask me, so I would interview myself,” she told me.)

Koppel opened with an unlikely hypothetical: he was tired of this “Nightline nonsense” and wanted “to make big bucks.” What was the formula for writing romance? Should he set his story back in the fifteenth century or medieval times?

“No, no, no,” Stephens said, refusing to take the bait. “You can do that, but then you are not writing a contemporary romance. That’s a historical . . . if you are writing contemporary, you are writing about right now.”

Koppel’s condescension gave the impression that he had not only missed the changes in romance writing but the seismic changes in women’s lives over the past few decades, the ones that had pushed them out of the home and into the workplace—the ones that inspired them to take charge of their sexuality, yes, but more importantly, their lives. These were the stories that Stephens wanted her writers to reflect.

“How torrid should I make this?” Koppel went on. “Should I, should I, uh . . . ?”

“Well, you have to be realistic,” she cut in, saving him from whatever he was trying to say. “You see, because we have lived through the sexual revolution, we are very sensuous. We are very sensuous beings, so it is sort of necessary to not stop at the bedroom door. You don’t have to be very descriptive, but you cannot fool your audience, you see.”

This brought up another puzzling issue for Koppel. Don’t men read these books?

Koppel looked down at his desk and half sputtered, half chuckled, kind of like a Victorian gentleman who’d just caught sight of a lady’s ankle.

“I hope you do, because if you’d like to know what American women want, it’s all in the books,” Stephens said, flashing a broad smile. At that point Koppel looked down at his desk and half sputtered, half chuckled, kind of like a Victorian gentleman who’d just caught sight of a lady’s ankle.

After a commercial break, Koppel brought an antagonist into the conversation: an associate professor of English at Westminster College, Patricia Frazer Lamb, who had made a study of romance novels and found them wanting. Lamb seemed to have come out of feminazi central casting, with her makeup-free pallor, smug demeanor, and pussy-bowed blouse that was the same shade of brown as her short wavy hair. She didn’t have a problem with fantasy or schlock or trash—“I love it, myself!” Lamb said emphatically—but she saw romance as bad news because it taught women that their highest goals in life should be marriage and child-rearing. Happily Ever After, to Lamb, was “a reality that is not going to be fulfilled in ten million years, and who would want it anyway?”

Lamb also explained, “I think these particular novels, because of the message, because of the needs out of which they are arising and the needs they fill, these particular novels, as I said before, are a really pernicious influence, and I think they are a kind of Valium for the mind or Valium of the emotions for women. And unlike Valium, they are truly addictive.”

Gliding over the fact that Lamb had just given Stephens’s trade a huge plug (the truly addictive properties of Valium were not yet widely known), Stephens countered that such reading matter “does not interrupt the daily life of the average American woman,” who, after all, “was not stupid.”

Stephens was one of the first to recognize that American women had moved beyond bodice rippers and were ready for something new. In retrospect, the Koppel interview captures Stephens’s personality in microcosm, revealing how she rose through the ranks of romance publishing. She was fearless in the face of challenges—whether it was ridicule or racism—qualities that would serve her well in the world of white male publishing. Others might have been defeated by rejection; Stephens was both accustomed to it and undaunted by it.

Still, like a lot of women, she attributed her success to good fortune and serendipity rather than force of personality or vision. “Everybody felt it was a strategic plan to do this,” Stephens said of her entry into romance publishing. “It wasn’t.”

When her career in fashion didn’t pan out in Los Angeles, Stephens took a job with American Airlines. At the time, the early fifties, the Urban League was encouraging Black workers to desegregate the airlines. (“You are a college graduate; how can they refuse you?” a friend posited.) The job was dull—Stephens checked passenger manifests after the plane took off—but she used her free flights to travel. New York, she realized, was a better fit for her ambitions. She moved into a YWCA women’s hotel on Lexington Avenue and 45th Street—two daily meals and housekeeping were included—and worked for a time in retail, at Macy’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Bendel’s, which was on its way to becoming the most stylish store in New York. She was 29, vivacious, and very pretty.

Her life over the next few years was a little like Holly Golightly’s—not the tragic character in Truman Capote’s novel but the one in the far more upbeat movie starring Audrey Hepburn. In Stephens’s recollections, she was forever finding job leads at cocktail parties. (“In 1963 the pop culture thing was to hire a Negro,” she told me.) Stephens talked her way into numerous jobs—first as the receptionist and then as a researcher at Huntington Hartford’s eccentric Show magazine, where she met photographer Herbert Migdoll (who later took her photograph for an exhibition of his work that hung at Lincoln Center). She also worked with Nan Rosenthal, who would eventually become a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and a young writer named Gloria Steinem. Stephens went to the March on Washington with renowned photographer Jill Krementz and a bus full of Broadway actors. “Everybody thought they were somebody, so nobody paid me any attention,” Stephens said of her life in Manhattan.

She also worked for several years at Job Corps, teaching, among other things, sex education to girls. But, as Stephens told a friend, she really wanted “to work with the movers and the shakers.” He helped her land a job as a researcher at Time-Life Books. And then, on a trip to North Adams, Massachusetts, she strolled into a bookstore and picked up a Harlequin Romance, which she bought for the grand sum of 10 cents. She went home and read it and then returned to the bookstore the next day and bought five more. I’d love to work for a publisher who makes these books, she thought. There was something about the genre that spoke to her, in particular a racy novel by Charlotte Vale Allen in which the protagonist was around Stephens’s age. Her love interest was bald—and therefore imperfectly realistic. Stephens began to imagine a quiet life for herself in which she could sit in a small office, day after day, reading. After talking her way into several more interviews and enduring a series of rejections (“Why don’t you become a writer, like Toni Morrison?” one personnel officer asked), she was hired in 1978 as an associate editor at Dell. She was 47.

“What does a heroine have to offer a worldly man if she’s not experienced in bed or on the job?” Stephens would ask.

Stephens was assigned to Candlelight Books, a wan imitation of England-based Harlequin, which dominated the romance market. “It was a department no editor wanted to be bothered with,” she said. “Nobody explained anything to me because no one knew and nobody cared.” But Stephens had an idea. She knew that the lives of American women were changing and the helpless heroines of Harlequin—British maids and Highland lasses—weren’t going to fly in a country where women were demanding equal rights. She did some independent market research, watching women buy romances by the bucketful at a Woolworth’s near her office. They weren’t buying Candlelight’s because, a customer told her, they were just too sweet. The heroines were ninnies.

That was when Stephens began looking for writers who could create female characters of substance. “What does a heroine have to offer a worldly man if she’s not experienced in bed or on the job?” she would ask. Authors like Kathleen Woodiwiss had already shown there was a demand for steamier fiction with the historical blockbuster The Flame and the Flower, in 1972, but Stephens wanted to update the model with women whose experiences more closely resembled her own.

Her first such book as an editor, Morning Rose, Evening Savage (“Vowing never to be poor or dominated again, Tara is shocked when Alek brazenly approaches her with the prospect of marriage”), sold so well that within eight months Stephens was editor in chief of Candlelight. In 1980 she pitched her bosses on a new, sexier line called Candlelight Ecstasy, which launched in December. One of that division’s first books, Gentle Pirate, about the relationship between the widow of a Marine killed in Vietnam and a one-armed battle survivor, became a blockbuster. It sold out its first printing within weeks and “surpassed the merely sensual and ultimately liberated the romance novel,” according to John Markert, the author of Publishing Romance: The History of an Industry, 1940s to the Present.

But Stephens wanted to do more. She began to seek out and publish writers of color, whose books were characterized as “ethnic romance” and sold on separate shelves in bookstores. Entwined Destinies was her first. Written by Elsie B. Washington, a Black Newsweek reporter who was also a friend of Stephens, it depicts a Black journalist who falls in love with a Black oilman. The book sold 40,000 copies on its first run, piquing the interest of the media. “The desegregation of the paperback romance novel arrives,” People magazine declared. Stephens found other writers who were Latina, Asian American, and Native American. Most were working women—flight attendants, secretaries, and so on—who had no choice but to get a job to support themselves. The white women who wanted to write were generally housewives looking for extra cash. At times, their husbands would accompany them to workshops that Stephens led, and they’d challenge Stephens’s assessment of their talents. Why are you buying my wife’s books? they would ask. Is she really that good? “The husbands felt like that plaything [their wives’ writing] was infringing on their work as a wife and mother,” Stephens said. “His wife had become alive in something that he had no part of and no control over.”

The sex scenes in the books didn’t dampen the threat. They were more sensual than sexual but did get down to specifics. During workshops, Stephens would suggest her authors read the best-selling The Joy of Sex. (One writer went home and unsuccessfully experimented with matchsticks to replicate the recommended sexual positions.) “I told my writers exactly what I wanted. The heroine had to have a certain age, a certain job. She had to be upwardly mobile,” Stephens said. “The hero was icing on the cake, because without him she could still have a full life. If she wanted flowers, she could buy them herself. She didn’t have to wait for a guy. It empowered women. It empowered them very fast. They were just waiting for someone to give them permission.”

By the end of 1982, Candlelight Ecstasy had sold 30 million books.

As Stephens was becoming a force in the world of New York publishing, another Houston woman, Rita Clay, was feverishly trying to break into the realm of romance writing.

If you google the Romance Writers of America, Stephens gets her one-sentence credit for creating the organization. But among the old RWA membership, the real credit goes to Rita Clay, now 78. Clay was a statuesque and gregarious adherent of can-do-ism. Like a lot of women who grew up in Houston—including Stephens—she was bitten early by the entrepreneurial bug. Her mother was a technical writer. As a girl, Clay read her mom’s romance novels in secret; it became her passion. Attending a local writers’ conference in the late seventies, she met a group of women who, like her, wanted to write romance. But Clay wasn’t satisfied with just a writers’ kaffeeklatsch that met in her living room, with kids running wild. “I knew what sold,” she told me.

She had some trouble getting her own career off the ground. For her wedding anniversary, in 1977, Clay’s then husband bought her a typewriter and declared, “You said you always wanted to write. Now write.” After two failed attempts, Clay sold her third manuscript, Wanderer’s Dream, to Silhouette Books.

Clay’s efforts at organizing were even tougher. She went to several writers’ groups in New York, looking for solidarity, but they were all run by men, who wouldn’t let women in the door. “There were men who were writing basically porn, with a beautiful woman and the ugly guy who is finally going to get his wish,” she told me. Undaunted, Clay kept going to writers’ workshops in Houston, ones that were big enough to attract the attention of New York editors. In 1979 she met Stephens, who had flown in to address a group of would-be romance writers and wowed the crowd.

Shrewdly, Clay kept building the relationship. Over the next few years, Stephens advised the group, providing contacts and connections, and urged them to professionalize by picking a name and a president. “What you really need is a conference of your own,” she told Clay, who took the idea and ran with it while Stephens lured speakers and financial sponsors from New York. That was how the Romance Writers of America was born, in 1980. (Each woman claims to have come up with the name for the fledgling organization.) The original membership of eight included five white women as well as two Black women—Stephens and her sister Barbara—and a Latina named Celina Rios Mullan. Eight hundred women attended their first conference at the Woodlands, in Houston. Clay and her band of writers presented Stephens with an Elsa Peretti bracelet from Tiffany to express their gratitude for her founding of the organization.

Clay doesn’t recall Stephens doing much more than that. “There had to be somebody who could reach out to the editors and the guys who were representing us,” she said. “She was a nice woman, and she was on the board because we knew we needed her.” (“What they did not understand about me was that I was their gateway to publishing and money,” Stephens said. “I was their passport, and they didn’t realize I fought for them when they couldn’t.”)

Clay also opened the RWA to all, “all” being not just romance writers but wannabe romance authors who were mainly readers, who in turn started forming RWA confabs in their own cities and towns; it became as much a social club as a professional organization. The members of color, who were generally more interested in making it as writers than in making friends, felt increasingly unwelcome and either left the organization or never joined in the first place. “There simply weren’t enough to count,” said Sandra Kitt, a best-selling romance writer who is Black. Or, she added, “there may have been members, and they may have been silent and pretty much invisible.”

Stephen Ammidown, from the Browne Popular Culture Library, gives credit to the work of both Stephens and Clay. “It took some guts to create the Romance Writers of America and not just the Romance Writers of Texas,” he said of Clay. “The reason that Vivian had influence at RWA was because she had power in New York and she was willing to push boundaries. Creating RWA was pushing boundaries.”

The falling-out over the next few years may have had something to do with the two women’s strong personalities. There was an argument over the organization’s nonprofit status—and its spending—after an over-the-top cocktail party on the Queen Mary at the 1983 conference. But the split probably arose more from different visions: by including readers and not just writers in the mix, the RWA became more like a sorority. (“It was like in high school and the mean girls running the campus,” said one former member.)

That left little room for improving the quality of the books, which was Stephens’s priority. “I would ask them, ‘Why can’t you be serious?’ ” Stephens told me. “I realize now that this group wanted the camaraderie of each other more than they wanted to write. They were so happy to find companionship I just let it go.” Stephens was the one who left, but she also felt abandoned, believing that the group was more attuned to Clay’s ideals than to her own. “They wanted Rita,” she told me. It was during this time—the early to mid-eighties—that the author Kitt found herself pretty much alone in the RWA as a published writer of color. A lot of the members, she recalled, came from a part of the country (or a part of their cities) where they had little to no exposure to people of color or people of different ethnicities and sexual orientations. “They weren’t their neighbors, who they went to school with, who their kids knew,” she said. “One of the things I’ve learned being African American in this country is that what people don’t know about frightens them, and when they get frightened, they get angry. They are afraid of change, of being pushed and marginalized themselves.”

Stephens devoted her energies elsewhere. In 1983 she was hired away from Dell to start an American line for Harlequin, which in the romance world was kind of like being hired away from Kohl’s to run Neiman Marcus. She told me she would have preferred to stay, but her boss wouldn’t match the $5,000 raise she was offered at Harlequin. “I find it interesting that they think because you’re a woman you are supposed to take what they give you.” Soon enough, she found herself having tea at Claridge’s with Harlequin’s founders, traveling across the globe in support of her books, talking to the Los Angeles Times and New York Times and, yes, Ted Koppel. She went to the Frankfurt Book Fair, the world’s largest. (Meanwhile, after Stephens’s departure from Dell, Black Enterprise reported, “Some black editors believe that Dell has bought the widely held myth that blacks don’t read.” During this time, in fact, it was common for editors across the industry to urge Black writers to change their characters to be white.)

And then, somehow, it all went poof. In 1984 Harlequin—which hadn’t been particularly excited about Black authors either—bought its major competitor, the American line Silhouette, which was owned by Simon & Schuster. Stephens was laid off in the shuffle. When the company refused to pay her severance, she threatened to sue, which in turn left her with a reputation as a troublemaker. “When Harlequin let me go, I didn’t hear from anybody,” she told me, a steeliness creeping into her voice. Supporting her was seen as aligning against a powerful publisher, something most writers weren’t willing to do. “Everyone was worried about their contracts or their agents.” But without her leverage, fewer writers of color found doors open to them in the romance world (or the publishing world, for that matter), an attitude that filtered down to the RWA. A friend once called Stephens to complain that she had just read a romance that contained a white writer’s description of a Black woman “who was as wide as she was tall, and her face was like a moon.”

Stephens was just past fifty by then. She did what a lot of middle-aged single women in New York do: she hung on in her small but beloved apartment. Unlike the characters in the books she loved, Stephens never found a partner to share her life with. “I had not had any strong relationships with the men I went out with. I had never met The One,” she said. Then she corrected herself. “I met The One once, and it didn’t work out. We were never on the same page at the same time. I was always looking for my next adventure.”

She supported herself as a freelance editor and book packager for several authors of color, but without the clout of a major publisher and the accompanying income, Stephens eventually grew tired of the fight. “I had really done what I was supposed to do. Manhattan is not a place to grow old.” In 2002, when an aunt left her $10,000, “that was enough for me to call Allied Van Lines and say, ‘Pack me up.’ ”

She headed back to Houston, alone.

There is a photograph that crops up often when you research Stephens’s life. It was taken in March 2016. She is at lunch at a white-tablecloth restaurant in Houston’s Museum District with three white women: two members of the RWA’s executive staff and the then president of the organization, Diane Kelly. Everyone has their hands in their laps, and some kind of ice cream and pastry dessert sits in front of each of them. Despite their smiles, the party looks a little stressed.

At that time, the racism roiling within the organization had not yet burst into public view. Stephens, who had mostly lived the life of a retiree since moving back to town, usually met with the RWA executive staff once a year or so, and the meetings were typically friendly, full of small talk. But during this lunch, Stephens told the women that she could see trouble was coming, and she had brought along the RWA magazine that featured photos of all the RITA winners, none of whom were Black, as a visual aid.

“Well, what do they want?” Stephens recalled one of the women asking.

“The same as you,” was her retort.

Stephens lamented that the genre had yet to produce great literature: “Jane Austen—I mean, she’s been dead for two hundred years.”

Stephens had several long-standing regrets about the romance field. She lamented that the genre had yet to produce great literature: “Jane Austen—I mean, she’s been dead for two hundred years.” And she was frustrated that the RWA was more concerned with internecine squabbles than with pushing the publishing industry to be more diverse. “When you don’t have enough, you hold on to whatever you have,” Stephens told me. “You don’t even know that if you open your hand you can have more.”

Stephens offered to help out as an adviser, but no one took her up on it. This experience was indicative of a leadership that seemed incapable of understanding the fury coming from members of color, who had long felt ignored and invisible while most of the white women partied on. The tension came to a head last fall, when a member of the RWA leadership incited a social media war after accusing a prominent romance editor of being racist. Pretty soon, a former RWA board member and ethics committee chair named Courtney Milan, who was herself a romance writer and—no coincidence—a former litigator, took up the gauntlet. Milan, who is Chinese American and had fought for years for diversity and inclusivity, could be abrasively blunt or bluntly abrasive. Either way, that quality put her in conflict with the old guard, who, in Southern belle fashion, stonewalled members of color by asserting that they could have equal treatment only if they asked for it nicely. (In a tweet, Milan once called a book set in the Scottish Highlands by a white romance writer “a f—ing racist mess.” And her response to a blue-eyed, half-Asian character was, “As a half-Chinese person with brown eyes, seriously f— this piece of s—.”)

Within three months, Milan was suspended and permanently banned from leadership, essentially for calling out members’ racism in a not-nice way. This in turn caused mass resignations (#IStandWithCourtney) and the cancellation of the RITA awards, as well as a slew of negative publicity for the RWA. (Membership started plummeting from roughly nine thousand to some six thousand.) This February, the board hired a prestigious law firm to conduct a very expensive investigation into Milan’s expulsion that found no malicious intent but some very sloppy decision-making. The appointment of a new board followed, and Milan, who had been invited back into the fold at the height of the crisis, received a formal apology in April. She declined the invitation to return.

Stephens could have declined too, when she got the May email about the Vivian award. Over the weeks when we spoke, it became clear that she still longed to be a part of the world she had created; that Stephens felt she had so much more to give that had never been acknowledged or appreciated in the past few decades, much less the months before and after the blowup. “I would tell them what they should do, but they probably wouldn’t like it,” she said. Like the women of color and their allies in the RWA, Stephens believed it was time for those long in power to step aside. “They have to remember that no banquet lasts forever,” she told me, adding, as she often did, “Everything works out the way it’s supposed to.”

That was true for me too. Stephens and I had tried repeatedly to get together over Zoom or FaceTime, with the virus raging, but technology was not her strong suit. (Her cellphone broke a while back, and she never bothered to get it repaired. Getting her on Zoom with her 2007 computer would have been akin to landing a plane from an air traffic control tower.) Eventually, we agreed that I would stop by her apartment for just a minute, dutifully masked and maintaining my distance.

She was waiting for me in the doorway, stooped and in pain from neuropathy, and leaning on her walker. She wouldn’t let me help her with the door. “It’s one thing about living alone: you learn to do for yourself,” she said. But when she finally sat down and took off her mask, there she was—the broad grin, the freckles, the warm but knowing gaze; still beautiful.

She was also still purposeful. Stephens’s computer was open to several windows, and there were to-do notes everywhere. She had prepared a file for me, copies and originals of clippings and photographs from that time when she had been busily creating what would eventually grow into a billion-dollar industry. She handed that over and then reached into a desk drawer for something else: the silver Tiffany cuff designed by Elsa Peretti, her gift from the original RWA members in thanks for all that Stephens had done.

To make sure I got the inscription correct, she had written it out for me on a separate piece of paper:

Vivian Stephens

Founder RWA

1st Annual National Conference 1981.

The cuff was badly tarnished, as if it had been neglected and nearly forgotten. But she loved it too much to let it go.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Pride and Prejudice.” Subscribe today.