In March 2007, Nick Pearce was running the thinktank the Institute for Public Policy Research. That month, one of his young interns, Amelia Zollner, was killed by a lorry while cycling in London. Amelia was a bright, energetic Cambridge graduate, who worked at University College London. She was waiting at traffic lights when a lorry crushed her against a fence and dragged her under its wheels.

Two years later, in March 2009, Pearce was head of prime minister Gordon Brown’s Number 10 policy unit. He had not forgotten Amelia and wondered to a colleague if the publication of raw data on bicycle accidents would help. Perhaps someone might then build a website that would help cyclists stay safe?

The first dataset was put up on 10 March. Events then moved quickly. The file was promptly translated by helpful web users who came across it online, making it compatible with mapping applications.

A day later, a developer emailed to say that he had “mashed up” the data on Google Maps. (Mashing means the mixing together of two or more sets of data.) The resulting website allowed anyone to look up a journey and instantly see any accident spots along the way.

Within 48 hours, the data had been turned from a pile of figures into a resource that could save lives and that could help people to pressure government to deal with black spots.

Now, imagine if the government had produced a bicycle accident website in the conventional way. Progress would have been glacial. The government would have drawn up requirements, put it out to tender and eventually gone for the lowest bidder. Instead, within two days, raw data had been transformed into a powerful public service.

Politicians, entrepreneurs, academics, even bureaucrats spend an awful lot of time these days lecturing each other about data. There is big data, personal data, open data, aggregate data and anonymised data. Each variety has issues: where does it originate? Who owns it? What it is worth?

On the face of it, open data is an idea too simple and right to fail. Assuming that the correct safeguards around private and personal information are in place, then the vast information hoards held by central and local government, quangos, and universities should form a resource for entrepreneurs who wish to start new businesses; private suppliers of goods and services who believe they can undercut the prices of existing contractors; journalists and campaigners who wish to hold power to account.

Economic innovation and democratic accountability would both benefit. Bureaucrats would learn more about how their organisations function and manage them better.

A good start has been made in publishing previously untapped public datasets, with some impressive early benefits. In the US, the federal government established data.gov, while in the UK data.gov. uk and the Open Data Institute were launched.

Transport for London (TfL), which runs London’s tube trains and buses and manages the roads, began to publish masses of information, much of it real time, about its services. This enabled developers to build applications for smartphones quickly, telling travellers about delays and jams. Commuters and goods deliverers could plan their journeys better. An estimate for TfL puts the savings as a result at more than £130m per year.

The Home Office, on the back of falling crime rates across the UK, was emboldened to publish very detailed, localised crime statistics. Analyses of prescriptions for drugs written by GPs show hundreds of millions of pounds worth of cases where cheaper and better drugs could have been prescribed.

The fast crunching of numbers by outsiders new to a field does not guarantee good results. The fact that family doctors prescribe the wrong things has been known for decades; so has the difficulty of imposing any rational management on doctors, who remain a powerful professional elite. Hospital doctors rightly point out that the publication of raw death rates for individual specialists can be misleading. It might look like a good plan to go to the heart specialist with the highest patient survival rate. But the best surgeons often get the most difficult cases, who are by definition more likely to die. “Transparency” can mislead.

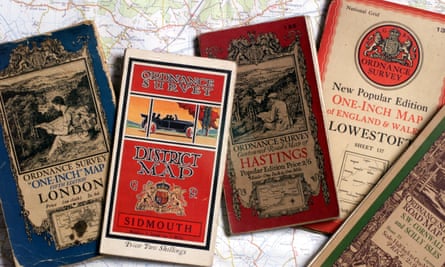

Open data also raises important questions about intellectual property. Patents and copyright have been great engines of innovation. It does not, however, seem right that the Ordnance Survey and the Royal Mail, both run for centuries by the government, should insist on their strict intellectual property rights over, respectively, mapping data and postcode addresses, compiled at the public expense. At the moment, they do.

The single thing that every citizen and every corporate decision-maker needs to understand is that the enormous data stores that government, government agencies, corporations, trusts and individuals hold are as much a key part of national and international infrastructure as the road network. Countries take national responsibility for ensuring that transport infrastructure is fit for purpose and protected against the elements and attack. They should take the same responsibility for data infrastructure.

The digital estates of the modern nation and the modern corporation are vast. Much of the architecture is designed to be inward looking, in the case of the nation, and cash generating, in the case of the corporation. They are not merely poorly tapped information libraries, although better access for citizens, entrepreneurs and researchers is important. They also enable much of everyday life to happen. Most of us would prefer our doctors to have our medical records when they treat us. Most of us would prefer not to lose the accumulated data on our friendship and business networks held by Google, Facebook, Microsoft and their wholly owned applications.

Property ownership is only as good as the national and local government ownership records. Wealth and income are only as good as the databanks of financial institutions. Some of this should be open, at least as metadata. Much of it should be utterly private, at least in the detail. All of it needs to be protected from attack, decay or accident.

There is no contradiction between the desire to live in a society that is open and secure and the desire to protect privacy. Open and private apply to different content, handled in appropriately different ways. One of us, Nigel Shadbolt, along with Tim Berners-Lee, is researching new forms of decentralised architectures that present a different way of managing personal information than the monolithic platforms of Google, Amazon, eBay and Facebook. And we both hope we are at the start of a personal asset revolution, in which our personal data, held by government agencies, banks and businesses, will be returned to us to store and manage as we think fit. (Which may be to ask a trusted friend or professional – a new branch of the legal profession perhaps – to manage it for us.)

Several companies have practical designs that offer each individual their own data account, on a cloud independent of any agency or commercial organisation. The data would be unreadable as a whole to anyone other than the individual owner, who would allow other people access to selected parts of it, at their own discretion. The owners will be able to choose how much they tell, say, Walmart or Tesco about themselves. One person might choose the minimum – here is my address to send the groceries to; here is access via a blind gate to my credit card. Another might agree that in return for membership goodies, it is OK for the company to track previous purchases, as long as it provides helpful information in return.

This has radical implications for public services, to begin with. Health, central government, state and local authority databases are already huge. They contain massive overlaps, not least because of the Orwellian implications of building one huge public database, which make the public and politicians very wary. The personal data model is one way to produce a viable alternative. There are obviously problems: how would welfare benefit claims be processed, if the data were held by the claimant, not by the benefit administrators? How would parking permits work? School admissions? Passports?

We are certain these are solvable problems. There are real gains to be made if citizens hold their own data and huge organisations don’t. The balance of power, always grossly in the big guy’s favour, tilts at least somewhat in each case towards the little guy. A lot of those small movements, added up over a lot of people, can transform the relationship.

There are encouraging signs here. Some government departments seem to be up for it in principle, and doing a small amount in practice. The public sector will start to do it where there are advantages for the politicians, bureaucrats or organisations involved. If a team of bright civil servants proves it’s cheaper for the state to let citizens hold their own tax records – because that way the citizens pay for the server time, the checking, the administration – a shine will rightly be added to the careers of those bureaucrats.

It seems to us that this requires very senior political leadership from the start and, probably, regulation at the end. The key, though, and where legislation may well be decisive, will be in the private sector, where widespread, perhaps wholesale, adoption would be needed, on which the public sector would, in part, piggyback.

Citizens concerned about data rights are unlikely to take to the streets in their millions. There are constitutional, democratic balance of power gains for citizens who manage their own public sector data, and we strongly advocate them, but there are cash gains and exciting new applications for the same people in their role as consumers. Mass opting-in to that will drive the change, if it is fostered by the powers that be.

How likely is it that this can be achieved? Indulge for the moment a contrary metaphor. The world wide web raced like a brush fire across the internet in the 1990s. One of the many reasons was the simplicity of hyperlinks. In the early days of the web version of these, the convention arose that they would be underlined and coloured. Tim Berners-Lee doesn’t remember who chose blue. But that colour emerged and stuck; like any successful mutation, it outlived other mutations, met the challenges of, therefore became an integral part of, its environment.

Nobody anywhere legislates on the colour of hyperlinks and still they are mostly blue. The logic is plain. Most designers want their link to be noticed, so they use the convention, so it becomes more established and a yet more effective signal. If the intended style of their page is different, and they don’t want their link to shout at the reader or prefer to use pink radio buttons or click-on photographs or whatever, they are free to do so and they do.

This is one of the many freedoms at the core of the success of the web and a powerful, neat metaphor for those freedoms. It may, however, not be the best model for a struggle to wrest our data back from big corporations, which, on the face of it, unlike web page designers, have big incentives not to co-operate. One of Berners-Lee’s many current ventures, arguably one of the most important, is the Solid project at MIT, which is constructing software to allow just the essential separation of our personal data from the apps and the servers that capture it, that we argue for above.

With Solid, you decide where your data lives – on your phone, on a server at work, on the cloud somewhere. Friends can look after it for you. At present, your book preference data may be with Amazon, your music preferences with iTunes, your Facebook friends hang out at a club owned by Mr Zuckerberg, etc. Solid aims to keep all these descriptor keys to your life in the one place of your choice.

Apps will need your permission before using your data and it may for a while be the new normal to refuse to let them, just because we can. Other parallel developers want to enable you to charge a tiny sum every time your data is used to advertise to you. At present, the big corporations do this on your behalf, then pocket the value of your interest. They sell your eyes to third, fourth and fifth parties.

In theory, the Solid platform could be used not merely to let you personally hold, for instance, your health and education data, a useful step in itself with which many healthcare systems are beginning to experiment. (Nobody cares more about my health than me and my family. So let me take care of at least one copy of the records.)

More radically, in principle, Solid or similar platforms could also hold all the information the government has about a citizen. Yes, yes, the spooks and cops want to keep their own files about terrorists and not discuss the morals of data retention much with the lucky names on the list, and we are perfectly happy with that. (We’d like more public discussion of how that data is compiled, the categories and facets of behaviour regarded as suspicious.) Yes, yes, data might often need to be compiled in a way that, while held by you, could not be amended or destroyed by you. Conceptually easy, surely?

It would need to include, in effect, a coded version that verified the open one. Therefore, we would need to trust government as to what the code contained. But this would be nothing like the present level of trusting them that unseen stuff, on unseen servers collated by lord knows who, is accurate. National insurance records, driving licences, benefit and council tax payment history in the UK, credit records the world over, could perfectly easily be portable, as long as, to repeat, the carrier isn’t able to alter or destroy key parts of them.

Clearly, the same must apply to court records, prison sentences and fines. We surely all actually prefer, whatever our views on penal reform, that somebody has a list of who is supposed to be in jail today and takes a roll call every day. Car registration plates perform many useful functions – reduction of bad driving and theft of vehicles – which require there to be unimpeded access to records. If we want people to pay the tax they owe, we need some system of collecting it and some way of knowing collectively that we have done so.

Imagination will be needed to turn all these into data stores held by individuals. The central requirement is that, if, for instance, you own a car, that fact and details of your car must be in your data store, whether you like it or not; authorised agencies must be able to look simultaneously at everyone’s store, to find a car they are interested in and must be able to do it without you knowing. (Only sometimes – they can tell me they are doing their monthly check for who has paid car excise duty and they and I will be happy about that.)

One further aspect should be noted. The ownership of the cloud estate, all that immense quantity of hardware consuming massive energy and holding vast quantities of data, is in the hands of a few private corporations and governments. Oddly, though, the total memory and processing power in all that cloud is small compared with the memory and processing power in the notebook computers and smartphones of the general population.

And that presents one of the most attractive alternative futures. Instead of power and information being corralled by the big beasts at centres they own, it could be dispersed across all of us, distributed, at the edge. This idea, sometimes called the fog rather than the cloud, is technically feasible. Data stores could be built into residential and office buildings, coordinated with a goodly proportion of the existing devices. On top of the political and social gains, there are at least two practical advantages.

First, there are so many trillions of less than microscopically small transactions in every use of smart machinery that, paradoxically perhaps, electricity actually has to travel such long distances in the process that the speed of electricity itself becomes a constraint on how fast things can happen. Making the building blocks of storage and functions smaller and local speeds them up and reduces latency. Second, if everything is in the same place, everything is as vulnerable as that one place.

Many local authorities and large corporations in the UK keep back-ups of all their information, and process local taxes and payroll, with the Northgate data organisation, which, up until 2005, kept its servers in a clean, modern office facility in Buncefield, Hertfordshire. Very sensible all round. Until early one Sunday morning, when the oil storage depot next door blew up, in the largest explosion heard in Europe in the then 60 years since the end of the Second World War, measuring 2.4 on the Richter scale. The Northgate facility disappeared.

Luckily, the timing prevented serious casualties; Northgate recovered rapidly and thoroughly with textbook resilience. But common sense argues for dispersion of important data infrastructure to as wide a geography as possible. The coherence with the Solid idea is obvious.

There are hopeful straws in the wind here. MasterCard, not well known for its insurgent bolshevism, has donated a million dollars to MIT to help develop Solid. The present writers strongly suspect that Solid will be adopted by a relatively small number of tech-savvy citizens, who will begin to strongly advocate it, and governments will then need to step in and make the commercial world tolerate it or better versions or rivals like it.

Unlike those blue hyperlinks, this is a step forward that will only happen with state intervention.