With Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil riding shotgun, the MC5’s leader fronts a worldwide tribute tour for his revolutionary band, pens a no-holds-barred autobiography, and still kicks out the jams like a mother at age 70.

New York City’s Irving Plaza is packed to the rafters—a sweaty mass of fans hollering their approval as the five-piece band onstage knuckles down to the closing power chords of “Call Me Animal.” The song is a two-minute blast of protopunk from the 1970 album Back in the USA, the second of just three official LPs released by Detroit’s legendary MC5. Back then, cofounder and lead guitarist Wayne Kramer was a cocksure 21-year-old with a militant vision of how music could empower a youth uprising. Now, amid the cheers, a much older but no less energized Kramer grabs the microphone and exhorts the crowd, his voice hoarse and his activist hackles on high alert.

“Before we go, I want to thank you all for coming,” he begins, the stage lights shimmering off his custom Fender Strat, emblazoned with the stars and stripes of the American flag. “But listen, I know our country is in a messed-up position right now. We have a third-generation white nationalist organized crime figure in the White House, and we just can’t allow this to continue. We have to get that bum out of there, and the way we do that is by exercising our democratic rights and responsibilities. Vote! Vote! And tell everybody you know to vote!”

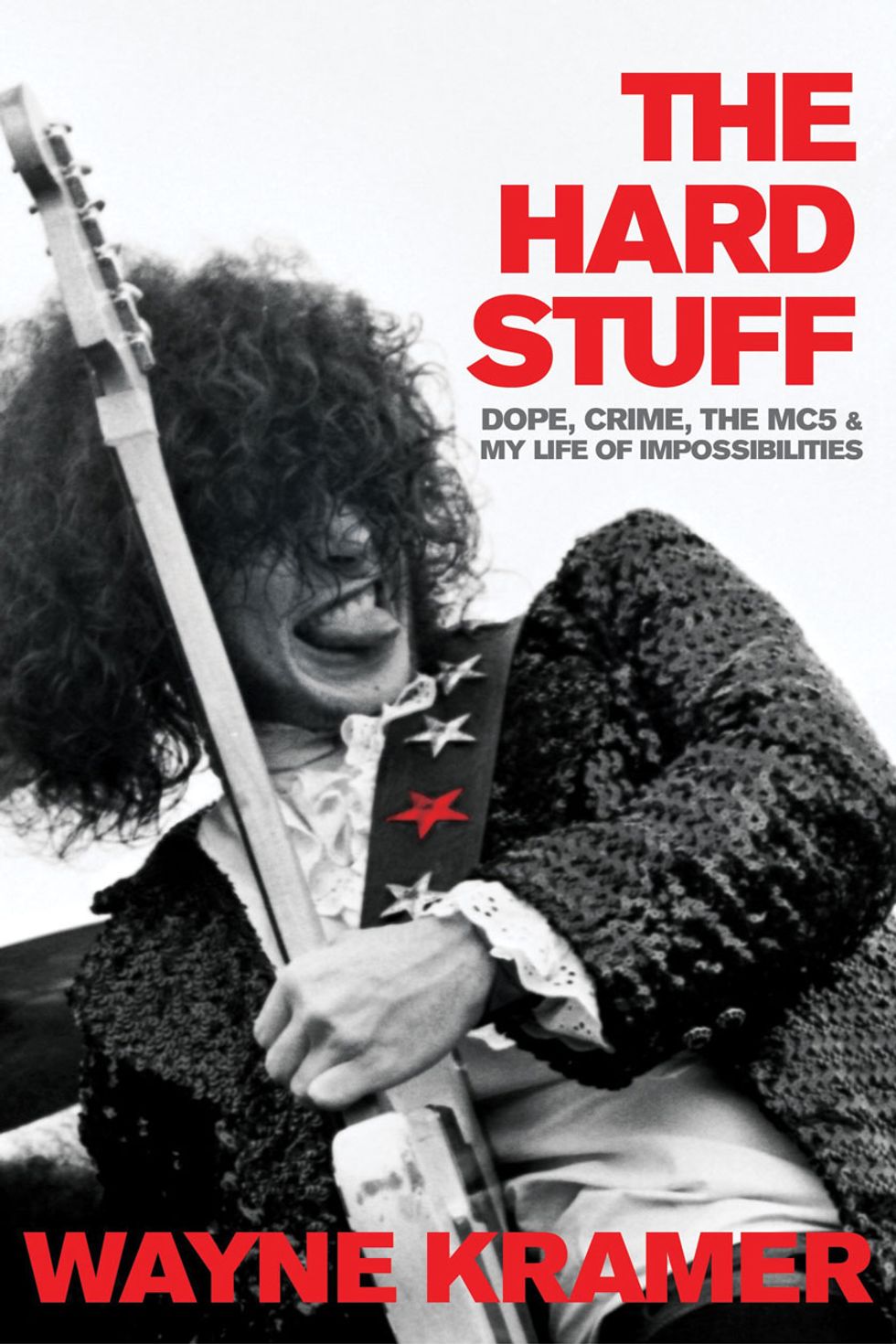

Whether or not you agree with his political views, the passion behind them is genuine. Kramer is now 70, but he still brings an idealistic exuberance to his music and his message. And for him, the message first came into clear focus more than 50 years ago, during the long, hot summer of 1967, when his native Detroit became a national flashpoint of civil unrest and rebellion. But, as he recounts in his compelling new autobiography The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, the MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities, his connection to the music started as innocently as it did for any other American teenager who grew up listening to Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry: with a guitar and a dream.

Describing his first Kay acoustic guitar as “the key to the locked room with all the answers,” Kramer was incurably swayed by the hypnotic power of rock ’n’ roll. “I needed to be in a real band,” he writes, and one by one, he found his kindred spirits. “A schoolmate told me he knew a kid named Fred Smith who played bongos. I figured a band could use a bongo player. I hunted him down, we had a chat about it, and he seemed interested.”

Under Kramer’s tutelage, Fred “Sonic” Smith picked up the guitar and became an accomplished rhythm player, and eventually a natural co-lead with Kramer. By 1967, after a few changes in personnel, the Motor City Five—MC5 for short—had coalesced into the now-classic lineup with Michael Davis on bass, Dennis “Machine Gun” Thompson on drums, and the imposing Robert Tyner on lead vocals. Their muscular, acid-fueled sound drew from the Yardbirds, the Rolling Stones, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, and even Motown and the avant-garde improvisation of Albert Ayler, but with a distinctly raw-and-dirty edge that reflected the knockabout blue-collar vibes of Detroit (a stance that Iggy Pop and the Stooges, brothers-in-arms to the MC5, embraced with equal fervor). And as if to drive the point home with a left hook to the jaw, the band’s Elektra Records debut Kick Out the Jams was recorded live and unhinged at Detroit’s famed Grande Ballroom over two nights in October 1968—the second one, aptly enough, being Halloween.

Kramer recalls the gigs today with mixed emotions. He’s especially hard on his own performance, as well as Elektra’s handling of the final album package. Even so, Kick Out the Jams hit No. 30 on the Billboard charts. Close to home, diehard fans saw it as a successful opening salvo in a grassroots narrative that the band had honed with the guidance of a local poet and firebrand named John Sinclair.

TIDBIT: Kramer’s account of his prison years in his new autobiography isn’t the usual harrowing tale. There, he met jazz-horn great Red Rodney, who became a mentor, and continued to master the guitar.

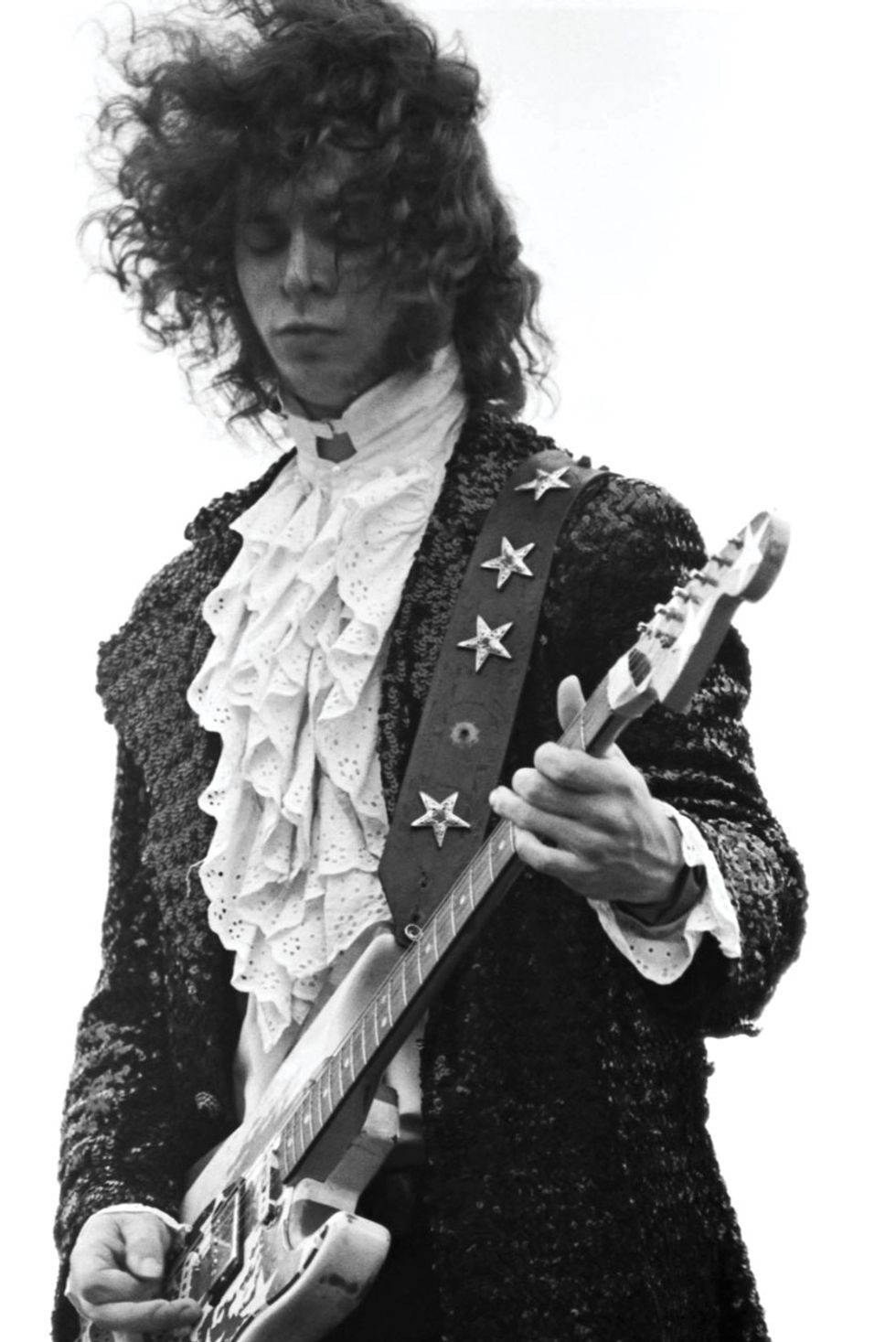

“You know, everything that we did, and everything that I tried to make happen in the ’60s, was out of a fundamental sense of patriotism,” Kramer insists. “I painted my guitar in the stars-and-bars motif, partially because I admired Pete Townshend’s Union Jack sportscoat, but also because I felt like the symbol of the flag was only being used to promote one side of the argument. If you follow the Framers’ intent, democracy is participatory, and if you don’t like the way the government is doing something, it’s your duty to say something about it. And one way I could do that was to co-opt the flag for my point of view. I could put an American flag on my amplifier to say, ‘I, too, believe in America, and I think the way you guys are running it is wrong.’ It’s my right and responsibility to do that.”

Kramer also took it as his right—or maybe more as his calling—to deconstruct the guitar by any means necessary. He started with Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” rhythms as grist, while Beck, Townshend, and Hendrix exposed him to sheer volume and multi-colored sheets of sound. In a cascade of buzz saw licks, Kramer seemed to flay the guitar to pieces over hyped-up anthems like “Ramblin’ Rose” and “Kick Out the Jams,” and yet he could ease straight into a loping, Albert King-style blues on “Motor City Is Burning,” or a psychedelic, feedback-laden freak-out on the freestyle jam “Starship,” which often clocked in at over 10 minutes if the band was properly, shall we say, lubricated.

Although Kramer, shown here in 1969, is a fluent soloist, his playing focuses strongly on rhythm. “We were more interested in the chords and how the rhythm pushed the song forward,” he says of his MC5 partnership with Fred “Sonic” Smith. Photo by Mike Barich

In the early days of the MC5, Kramer went through a Fender Esquire, a Gretsch Duo Jet, a Gibson ES-335, and a ’57 Les Paul (which he might have stayed with for good if it hadn’t been stolen), but eventually he landed on the Strat, which he “hot-rodded” with a middle humbucker for extra oomph on his solos. Along with an Epiphone Wilshire and an oddball Dan Armstrong Lucite model, the Strat became one of his main stage guitars in the late ’60s.

“At one point, I just said ‘gimme a Fender’ because they’re sturdy,” Kramer recalls. “I was tired of being worried about breaking the guitar all the time. And besides being good for playing in a band, they’re a pretty solid weapon in a gang fight, too, you know?”

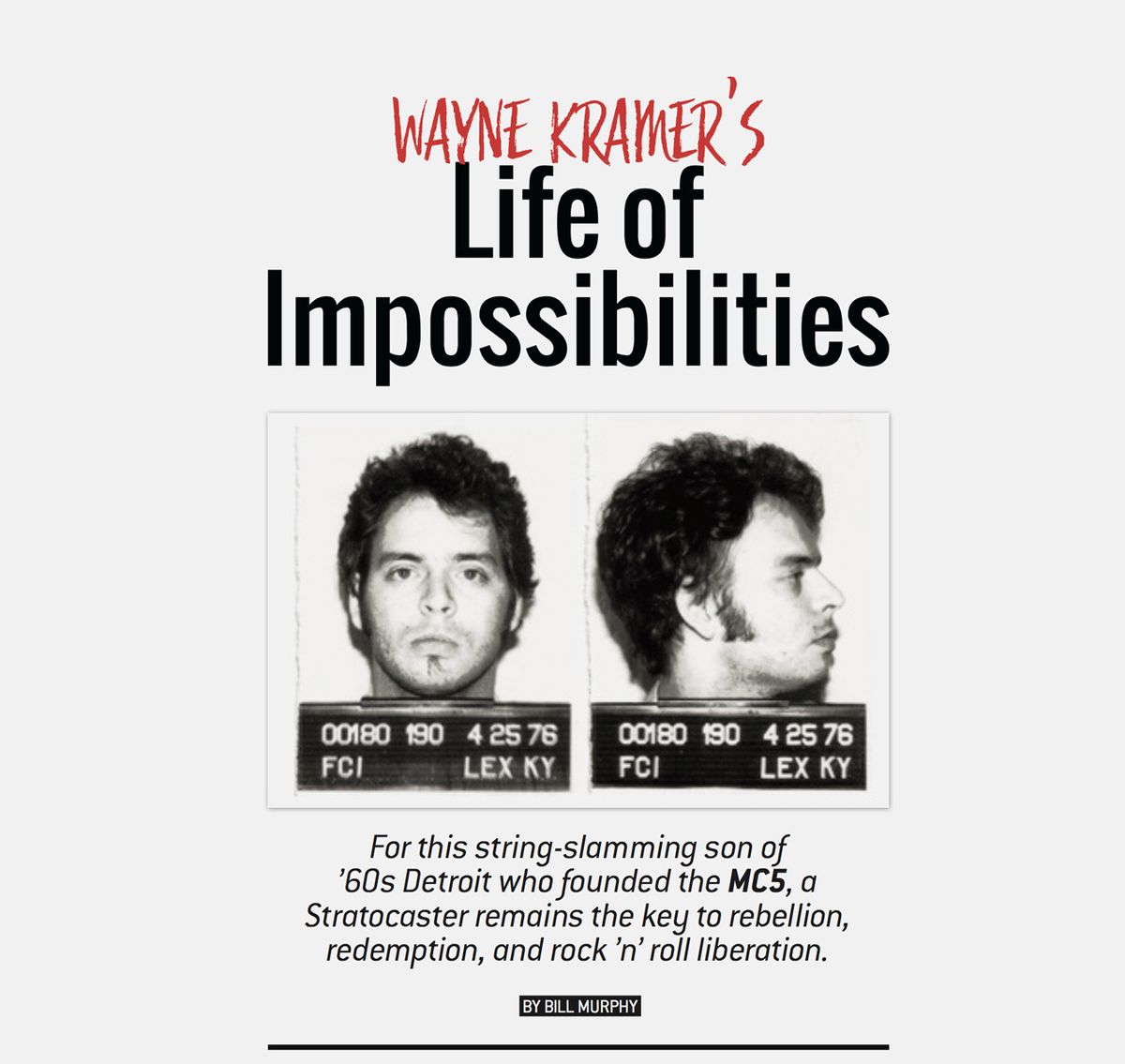

Volatility was at the heart of the MC5’s ethos, and ultimately it proved their undoing with their last album, 1971’s freewheeling and funky High Time. The aftermath wasn’t kind to Kramer. He developed a dope habit and fell into petty crime to support it. In 1975, he was busted trying to sell cocaine to a federal agent, which landed him in Lexington Federal Prison in Kentucky. By a stroke of good luck, he met the trumpeter Red Rodney inside, who schooled him in jazz improvisation. After his release, he bounced between Detroit and New York, hooking up with Johnny Thunders and then Was (Not Was). He lived in New York for most of the ’80s, then moved to Key West, then Nashville, and then L.A., where seemingly against all odds he landed his first solo deal with Epitaph Records and released an album, The Hard Stuff, in 1995. It was a well-received comeback, featuring guest appearances from members of the Melvins, Bad Religion, and Suicidal Tendencies, and led to three more recordings with Epitaph.

Kramer relives all this and plenty more with remarkable candor and self-reflection in The Hard Stuff, the book. As rock ’n’ roll memoirs go, it’s a turbulent rollercoaster ride with dizzying highs and harrowing lows, but it concludes with a storybook ending of recovery, redemption, true love, and the gift of fatherhood.

And it couldn’t have happened to a more worldly guy. In recent years, Kramer has begun reaping some rewards from his long slog in the trenches. The MC5 has been nominated four times for entry into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, including this year. Understandably, Kramer says he’s not holding his breath, but this time the moment feels right. In 2011, Fender finally celebrated his achievements, having worked directly with him for more than a decade to replicate the sound, feel, and distinctive look of the American flag Strat he modified with the help of graphic designer Robin Summers back in the late ’60s.

“For a guitar player, it doesn’t get any better than that,” Kramer says with pride. “I mean, that’s the crowning achievement for a career. I was honored beyond belief, and humbled by their vision and their generosity. And I still am. I love Fender. They make good instruments, smart men and women work there, they support me, and they help us a lot with Jail Guitar Doors, too.” (Named for a song by the Clash that was actually written about Kramer, the Jail Guitar Doors organization was founded in 2007 by Billy Bragg to bring musical equipment to prison inmates in the U.K. Kramer started a U.S. chapter in 2009.)

Kramer repainted and sold the original Strat long ago, but the replica figures prominently in the MC50 tour he organized with Soundgarden’s Kim Thayil (who’s still playing his own signature white Guild S-100 Polara). Joined by Fugazi’s Brendan Canty on drums, Faith No More’s Billy Gould on bass, and Zen Guerrilla frontman Marcus Durant, the group somehow captures the primal energy of a bygone era, and yet the political urgency feels current—from the sensual double-entendres of “Come Together” to the lust for freedom depicted in “An American Ruse.” At first, Kramer wasn’t sure how Thayil would react to the invitation, coming barely a year after Chris Cornell’s death. But now there’s talk of more touring next year, and maybe even a new album—a prospect that wouldn’t be remotely possible, Kramer acknowledges, if they weren’t enjoying themselves.

“I’ve known Kim a few years,” he says, “and I know how I’ve felt losing band members and people around me. And I thought this might be just the thing to get him back out in the world. Losing your loved ones, you know, you never really get over it. You go on with your life, but I don’t think there is any such thing as closure. It’s a pain that you live with for the rest of your days. Maybe it had been enough time, and maybe it wasn’t. I didn’t know, but I called him up and said, ‘Look, this is what I want to do. Do you think it would be fun?’ And he thought about it for a few minutes and he said, ‘Yeah! I think it might be fun. Let’s talk some more.’ And we were off to the races.”

Let’s hope they keep on running….

Guitars

2011 Wayne Kramer Fender Signature Stratocaster (based on a ’67 or ’68 Strat with a rosewood fingerboard, a Seymour Duncan humbucker in the middle position, and two vintage-style single-coil Strat pickups)

2012 Epiphone 1966 Worn Wilshire reissue

Amps

Fender Hot Rod DeVille 212 combo

Fender Super-Sonic 60 212 extension cab

Effects

DigiTech RP500

Strings and Picks

Fender 3250R Super Bullet strings (.010–.046)

You and Fred [“Sonic” Smith, who passed away in 1994] shared a real sense of interplay on guitar that was a bit ahead of its time. In the book, you mention how you guys got to a point where each of you knew instinctively where the other was going.

Well, we played together so long, and from such a fundamental starting point. We were both 12, 13 years old. I had been playing for a few years, so I knew a few more songs and a few more chords. But I spent one summer working with Fred, showing him everything I knew, and after a while we were equals. We loved certain kinds of guitar playing—especially stuff from a rhythmic perspective, as opposed to single-note solo playing. We were more interested in the chords and how the rhythm pushed the song forward.

Chuck Berry was our main man. We learned how to play that Chuck Berry rhythm guitar figure for five or 10 minutes without stopping, using all downstrokes, grinding it out with the cramps that you get in your forearm.

I know them well. It’s not easy.

[Laughs.] I know only guitar players know what we’re talking about! But we were young and it was worth it, because when you played for people, you knew that you could drive it. You were propelling this music forward. So for a long time, I was the soloist and Fred was the rhythm guitar player. And then around ’68 or ’69, Fred just exploded as a soloist. He’d really developed original techniques and his own voice. He didn’t play like the British blues players—like Eric Clapton or Jeff Beck or Jimmy Page. He had his own whole thing. I mean, both of our styles were based in Chuck Berry, but he found a way to branch out of that.

So we spent a lot of time improvising, just playing for hours and hours. And if you play with another guitar player long enough, you exhaust everything you know, and then you start playing what you don’t know, and you get into something good. We just found that we could play syncopated rhythm parts simultaneously, and they would lock in perfectly, or we could solo simultaneously and they’d still lock in. These were just little techniques that we developed over 10,000 hours of playing together.

Ultimately it became, in my humble opinion, the strength of the MC5. The guitar playing was original, and no one else was doing anything like that at the energy level and with the velocity that we could do it. And then once we started listening to free jazz, and started leaving the beat and the key behind, then we really stretched out and got into a whole new thing.

“I painted my guitar in the stars-and-bars motif, partially because I admired Pete Townshend’s Union Jack sportscoat, but also because I felt like the symbol of the flag was only being used to promote one side of the argument,” says Wayne Kramer, of the paint job on his original MC5 Strat. Here, he brandishes his modern Fender Custom Shop signature version. Photo by Ken Settle

Fred preferred a Rickenbacker 450/12 with humbuckers, which led you to modify your Strat, too, right?

Yeah. What happened was, I couldn’t quite get my solos louder than him to jump out in front of the sound of the band. We weren’t very good at dynamics yet, so everything was balls-to-the-wall. It was very difficult for us to learn how to play quieter—how to break it down and leave yourself some headroom. So my solution was, “I’ll put a humbucker in the center position, so when I want to play a solo, I can switch over and I’ll have just enough boost in gain and tone so that my solos jump out in front a little bit.”

And you know, I really wanted the band to be dynamic visually, too. I wanted banners on the stage, and streamers and flyers and flashing lights—anything that we could think of to make it look like a celebration or a rally or a religious ceremony or something more than just a band standing there. So one idea was let’s put flags on the amps, and in the beginning I made my own Jolly Roger—a big death’s head on a black background, as kind of a pirate symbol—and then later I just went with the American flag.

You also write about how you were using Vox amps for a little while.

We had the Super Beatles—100-watt tube amps from England. I think we went to Sunn after those. They had come out with the Spectrum I or Spectrum II, but they weren’t very consistent. The amps would work for a few shows and then they’d blow up. So we went to Marshall, and, you know, in those days, all the amps were imported from England, and they were used to running on 220 current. Local distributors would have to put step-down transformers in them, and they would also blow up all the time. In the MC5, at one point I think we had about nine of them. We’d carry six on the road with us, and three would always be in the shop. You had the one you were playing through, the backup for when that one blew up, and then the other one in the shop that hopefully we could get out whenever we got back to Detroit.

What are you and Kim using now?

We’re both playing through Fender Hot Rod DeVilles, with the 212 Super-Sonic cab. I wanted the extra speaker cabinet to push just a little more air. The Hot Rod DeVilles have all the power you need, and a great crunchy tone. We also don’t have to play at the volume levels that we did back in the day. Today sound reinforcement systems are very sophisticated, so if you get a good sound onstage, they can make sure that gets out to the audience. I’m always surprised when I read about bands like AC/DC that actually do use 12 Marshall stacks. Oh, my god! I know my hearing is damaged. These guys … they must be deaf as fence posts!

Have you had a particular stompbox or effect that you relied on?

Well, back in the day, I had one of the first Fuzz-Tones. It must have been ’65 or ’66. That was the Maestro, and I was kind of underwhelmed with it. I thought it was a nice sound effect, but it didn’t really light a fire under me. I found I got a better sound by turning the amp up all the way. That natural harmonic tube distortion—that’s the sound I wanted.

Then later on I got a Fuzzface, which I liked, and a [Cry Baby] wah-wah. I used those in the MC5, but in the intervening years I moved away from stompboxes. As they got more ubiquitous and sophisticated, they started sounding worse to me. I didn’t use them for a couple of decades until I got a job with Marianne Faithfull. I figured she would probably like it if I had some modern effects on the guitar to gloss up the sound, and I’d been working with Tom Morello, and he’s so creative with the tools that he uses that I was kind of stealing some ideas from him. Well, I wasn’t kind of stealing them—I was stealing them. [Laughs.] So I got a DigiTech RP500, which is a multi-effects unit. This has the Whammy in it, along with every other effect that’s known to man—fuzz tones, delay, backwards chorus—you know, everything in one place. I won’t be bending over wriggling any cords, and I can pre-program it for the set I’m playing. And I’m using it now on the road.

You know, going back to The Hard Stuff, there’s another passage where you describe your first encounter with the insurgency that roiled Detroit in the summer of ’67. You talk pretty vividly about how exciting and terrifying that moment was. You were just a teenager at the time, but did you see music back then as a way to connect people who couldn’t resolve their differences?

That was just starting to emerge in our thinking. It was important for us to address the concerns of the audience, because they were our concerns, too. And I think that’s the thing that separated us from our contemporaries. We weren’t trying to be blues aficionados or the next Bob Dylans or the next anything. We were trying to be a community band—the people’s band. We saw ourselves as members of a larger community of young people that didn’t agree with the way things were going, and wanted to make a change for the better.

And that’s the essence of rock ’n’ roll, isn’t it?

It is. You’re absolutely right.

With flamethrower energy, the MC5 blaze through this classic performance of one of their signature tunes, “Kick Out the Jams.” The song’s title came from the taunt the bandmembers shouted at other groups they felt didn’t deliver the goods onstage.

Nearly 50 years later, Wayne Kramer, at 70 years old, is still kicking out the jams, swinging his signature Stratocaster like a battleaxe as the song starts and digging into a wailing solo after 90 seconds.