Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century

A recent NPR article entitled “Same-Sex-Marriage Flashpoint: Alabama Considers Quitting The Marriage Business” included a photo of two African American women with wide smiles and joy evident in their posture. In the image’s foreground, one woman holds up a piece of paper in her left hand with her wedding ring and engagement ring clearly visible in the margins of the image. The paper, with an official seal just visible at the bottom, has neat script and calligraphy at the top that reads, “The State of Alabama, Jefferson County, Marriage License.” These women, Olanda Smith and Dinah McCaryer, married on February 9, 2015, the day that their marriage became possible in the state of Alabama. Their rush to the courthouse was savvy. As the story notes, in counties all over Alabama, February 9, 2015, was the last day that many municipalities issued marriage licenses to anyone at all. The article describes legislation passed by Alabama’s Senate that would end marriage licenses in the state. Instead, the law would require heterosexual and homosexual couples to record marriage contracts at probate offices. As one official supportive of this legislation put it, “Basically we’re getting Alabama out of the marriage business.” Why would Alabama do this? The short answer is that changing the law would excuse officials from issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

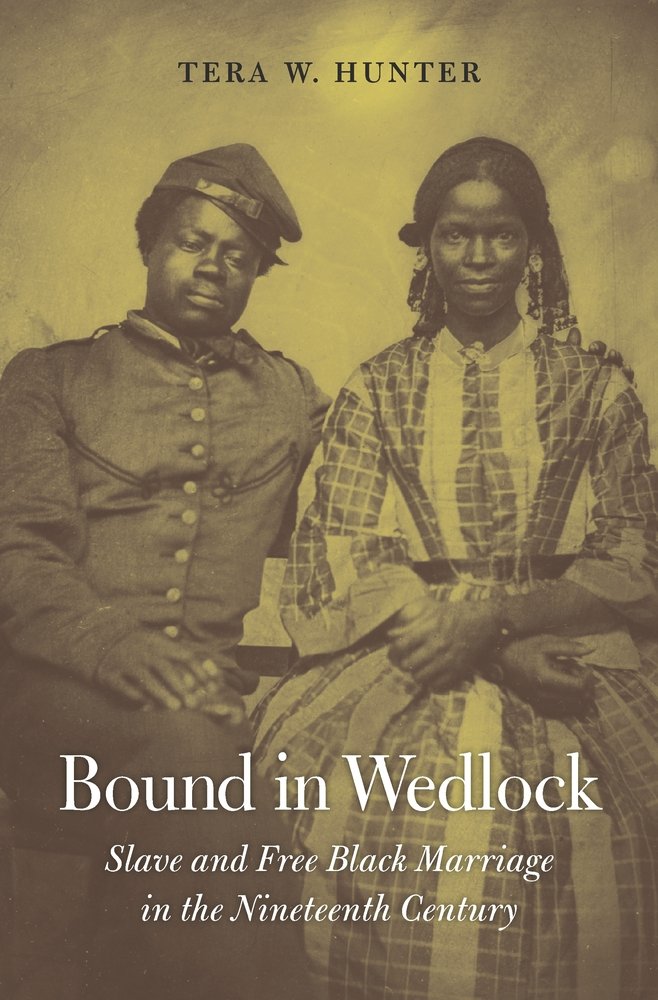

Historian Tera Hunter describes similarly-disposed officials in her new book Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century. At issue in the years following the Civil War in the former Confederate States of America were the marriages of former slaves, unions that some whites did not want the law to legitimate. She writes, “Many local jurisdictions throughout the South demanded high fees to discourage ex-slaves from marrying or simply refused to give them access to courts or licenses”(241). The federal government opened up legal marriage, a legal institution that many nineteenth century Americans valued as the bedrock of society, a requirement of manhood and womanhood, and the only appropriate foundation of a family unit, to include former slaves during and after the war. Those chafing at social change in the post-emancipation South saw Black marriages as a challenge to social order and racial hierarchy.

Bound in Wedlock provides a timely reminder that the right to marry and marriage law has long been a battleground for social justice and equality. It has only been fifty-one years since Loving v. Virginia made anti-miscegenation laws, statues that prevented interracial marriages, illegal. Local legislatures denied enslaved people the right to marry in the United States beginning in the nation’s colonial history. Slaveholders regularly split up couples, overrode the parenting decisions of enslaved mothers and fathers, and sexually abused their human property with no fear of punishment. Slaveholders went as far as espousing the idea that African Americans were unable to make family attachments, that Black parents had little regard for their children, and that white slaveholders acted in a parental role in the lives of their slaves. This paternalistic myth of kind slaveholders and childlike slaves remained embedded in early representations and histories of American Slavery into the early twentieth century.

Bound in Wedlock interrogates both the family-making practices of Black people in the nineteenth century and the evolution of marriage as an institution in the same period. Kinship was essential to Black people and many free and enslaved people valued marriage as a way to signify commitment and love. Marriage was a way to codify intimate relationships. However, it was also an expression of humanity. It was a right that could confer other rights, and it was an instrument of social control. Marriage was not a failsafe institution with the ability to right racism’s wrongs. The couples who jumped brooms, rushed to Union camps, or searched for each other in the chaos of the postbellum South thought marriage was important, not perfect.

Hunter juxtaposes the ways that African Americans practiced family formation, kinship making, and marriage with how the state, officials, and African Americans shaped marriage as a legal and civil institution. The first three chapters of the book consider marriage during slavery. In chapter one, “‘Until Distance Do You Part,’” Hunter discusses how enslaved people negotiated intimate relationships and built families knowing that their owners were not bound to respect them. Hunter challenges readers to acknowledge the multiple family formations and couplings that enslaved people chose and maintained. In chapter two, “‘God Made Marriage, but the White Man Made the Law,’” she further establishes marriage’s civil and legal implications by asking why whites made marriage illegal for enslaved people. Hunter looks at the important role that marriage as a civil institution played in the Dred Scott decision—the 1857 Supreme Court case that denied Scott, and African Americans at large, the right to buy their own and their family’s freedom— to demonstrate the legal and social stakes embedded in marriage. Chapter three, “More than Manumission,” wraps up the antebellum section of the text with a close look at marriage law and the lives of free people of color including mixed status unions, marriages between free and enslaved Blacks. In all three chapters Hunter centers Black family formations. African Americans formed families and adopted people into their kinship networks despite white disregard. Also, they affirmed their humanity among each other in spite of the violence, rape, abuse, and looming specter of separation through the internal slave trade.

Hunter then moves on to the Civil War years, examining the War’s impact on Black family life. In chapter four, “Marriage Under the Flag,” Hunter discusses the flurry of marriages in contraband camps during the war. While missionaries, the US government, and freedmen seemed to agree upon the importance of marriage as an institution, these marriages also exposed deep cultural and social fissures between all three groups. Significantly, legal marriage came with a legally enforced patriarchal family structure under which some former slaves did not wish to live. Legal marriage did not protect every type of family formation, and it limited women’s ability to play the economic and social roles they played in enslaved families. In chapter five, “A Civil War Over Marriage,” Hunter explores the political and legal arguments among federal authorities and between leaders in the Confederate States of America regarding Black marriages. On both sides of the battle lines, Black marriage caused friction between legal and religious authorities because married independent freedmen with families did not readily serve white supremacy in theory or practice. Instead, marriage conferred manhood on freedmen and slaves in ways that made many whites uncomfortable. Marriage and family structure, therefore, in the eyes of many, needed to be shaped and policed to benefit existing power structures based on racial hierarchy.

The final section of the book looks at Black marriages in the post-war period. In chapter seven, “The Most Cruel Wrongs,” Hunter again juxtaposes Black family formation and white prerogatives for legal marriage. While African Americans worked and hoped to reunite their families, whites in both the North and South wanted their support for heterosexual marriage and cohabiting nuclear families to help them control Black labor in the South. In a region decimated by the Civil War, Black labor remained essential to white wealth accumulation and survival. White landowners, in particular, hoped that statutes like vagrancy laws, punishments like convict leasing, and debt peonage in the form of sharecropping would discipline a newly-free Black labor force. Hunter covers how each of these post-war institutions policed family formation, focusing on the ways in which whites frequently used violence to threaten family life. In Chapter eight, “Hopes and Travails at Century’s End,” set in the early days of Jim Crow, Hunter looks at how African Americans defined and characterized marriage. Hunter looks at data about marriages among Black people in the period and surveys how family formations changed post-emancipation. She notes first how much value elite Blacks placed on the institution and how racism, sexism, and classism helped elites to define marriage narrowly at the same time that racist institutions devalued Black life. This narrow definition, Hunter makes clear, was born of post-slavery realities, politics, and repression, not in slave quarters or the extended kinship networks of the early nineteenth century.

Taken together, with Bound in Wedlock Tera Hunter makes a significant contribution to the historiography of American slavery and emancipation, a field in which the Black family, narrowly defined, has featured as a significant category of analysis. As Hunter writes, “African Americans were not attached to a family structure, they were attached to a family sensibility”(206). Before and after slavery, African Americans fought hard to preserve their families, build lasting kinship networks, and survive cruelty and hardship. While Hunter is clear that her study looks at heterosexual relationships, her engagement with non-monogamous relationships and kinship structure leaves room for queering where past studies have not. Hunter pushes readers to move beyond stagnant definitions of marriage and family and instead to listen to the Black sources she engages opening up room for a multiplicity of intimacies.

Marriage remains contested ground. In Alabama, the legislation needed to “get out of the marriage business” still needs to pass in Alabama’s House, where it currently awaits a second reading. Meanwhile, legislators have proposed similar bills in Oklahoma, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, and Montana. Marriage equality remains far from secure. Which families, which marriages, and which lives matter remain salient questions. Enslaved people, freedmen and women, and those who came of age at the dawn of Jim Crow endured, remained savvy about legal structures, and agitated for their rights. Their stories hold lessons for us all.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.