Editorial: Psychiatric hospitals, like jails, require releases in the COVID era

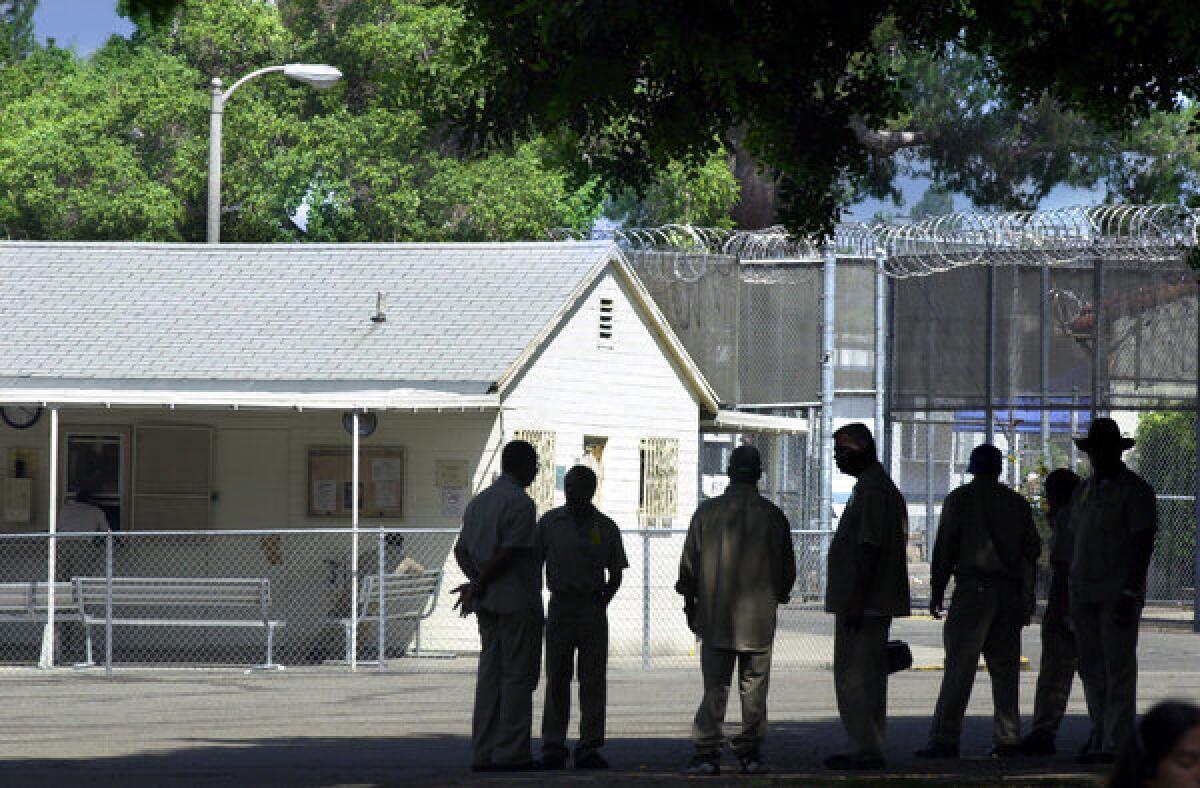

A deadly COVID-19 outbreak at Patton State Mental Hospital in San Bernardino is a horrific reminder that locked psychiatric facilities, just like jails and prisons, are jam-packed incubators for disease that should be made safer by judicious but significant releases and by alternative placements.

More than 250 people at Patton — at least 112 patients and 147 staff and other workers on site — have tested positive for the virus. So too have at least 66 patients and 58 staff at the Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk. Cases are also in the double digits at Coalinga, where two have died, and infections have been reported at each of California’s other two state mental hospitals, in Napa and Atascadero.

Several Patton patients filed suit last week seeking transfers to safer settings.

As with other densely packed institutions where people congregate and have little ability to practice social distancing, psychiatric hospitals have seen cases spread rapidly once the disease is introduced. The virus makes no distinction between patient and therapist, so it does not help that patients are locked in; the virus is not. Staff enter and leave state mental hospitals daily and can unknowingly spread infection to their families and neighbors. The Atascadero State Hospital is the largest single employer in Atascadero, but workers also come home to communities up and down the Central Coast. The Bay Area, the San Joaquin Valley, the Inland Empire and Los Angeles County are similarly vulnerable.

California’s psychiatric hospital complex is a fraction of its former size; it now houses and treats chiefly people accused of crimes but deemed incompetent to stand trial, people found not guilty by reason of insanity and people committed because they’ve been deemed gravely disabled under the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act. Removing such people from state hospitals sounds scary, and in some cases it is. Not everyone is suitable for alternative placement in motels or with family. But many are, and the danger can be greater when leaving people in than moving them out.

Meanwhile there’s a backup of people waiting to get out whose treatment is completed but who have nowhere to go, and a backup of people waiting to be moved in from jails that are also unsafely crowded. Many of those currently in the institutions have conditions that make them especially vulnerable to COVID-19 — the elderly and those with diabetes, heart conditions and other medical disorders.

Like jails and prisons, the hospitals are not safe zones that protect patients and their home communities. It’s often the opposite. Even in the best of times the state should make it a top priority to get people out of institutions and into community care, leaving a few remaining institutional slots for those special cases than can be handled no other way. It’s even more urgent now, in the era of COVID-19, to reduce the institutional population in the name of better, safer care, not just for the patients, but for all of us.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.