Back in the 1980s, Keoki Skinner was a reporter with a newspaper called the Arizona Republic. He covered the drug trade and the border, and he spent a lot of time in different parts of Mexico. But eventually, he got tired of traveling and of being a stranger in every place he went. He wanted to actually settle down in Mexico and to make a life for himself there.

Keoki moved to Agua Prieta, Mexico — a town right on the border where he’d done some reporting before. Agua Prieta sits just across the line from Douglas, Arizona. The two cities are contiguous — one urban area that spans the border, divided by a towering, rust-colored metal wall, a steep concrete ditch, a line of concertina wire, and a mesh fence.

Keoki ended up scaling back his full-time reporting job so he could open a smoothie shop and juice bar. He named the shop “El Mitote,” which in Spanish roughly translates to “a gossip spot.”

And it wasn’t long before Keoki started hearing gossip about some of the new customers in his shop. It was 1989 when they first started showing up. They had a certain swagger and attitude, and he says they often had bodyguards with them. Keoki described them as “Sinaloa Cowboys.” They wore high-end cowboy boots, Levis, and leather vests. They would double-park outside his shop and generally behave as if they were above the law. “Everybody just kind of stayed away from them,” says Keoki. “Because they knew what was going on.”

Sinaloa Cowboys

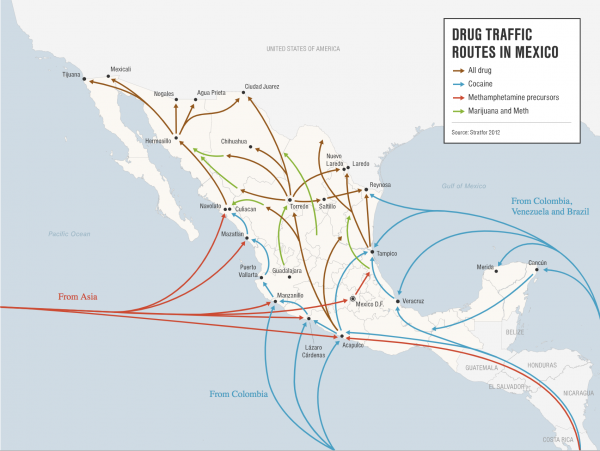

Back in the late 1980s, the Sinaloa Cartel wasn’t quite the sprawling criminal organization it’s become today, but it was headed in that direction. The cartel controlled much of the drug-trafficking corridor that ran through the Mexican states of Sinaloa and Sonora, then across the border into Arizona, and on to big distribution points like Phoenix and Los Angeles. Agua Prieta fell right along that corridor.

Keoki says there was one new guy who stood apart from the rest of the Sinaloa Cowboys. He dressed and acted more like a businessman. His name was Francisco Rafael Camarena Macias and he claimed to be a lawyer from Guadalajara. He told Keoki he’d come to Agua Prieta to build houses and that he was also pursuing business opportunities across the border — in Douglas, Arizona.

It wasn’t yet clear to Keoki that Camarena was also in the drug trade –and it would take almost a year for that to become apparent to the entire city of Douglas as well.

Douglas, AZ

Douglas, Arizona is a small town. Back in 1989, when Camarena arrived, about 14,000 people lived there. Camarena was outgoing and social, and he became friendly with some of Douglas’ most prominent citizens, including the chief of police and a local justice of the peace who owned a lot of land.

Camarena eventually bought a plot of that land near an industrial part of the border — and he also bought the local business that sat on it. The business was called “Douglas Redi-Mix,” and it sold sand, gravel, and concrete for construction.

Under the ownership of Camarena, the business appeared to be above board, bidding on building projects and employing local people.

A Suspicious Construction Project

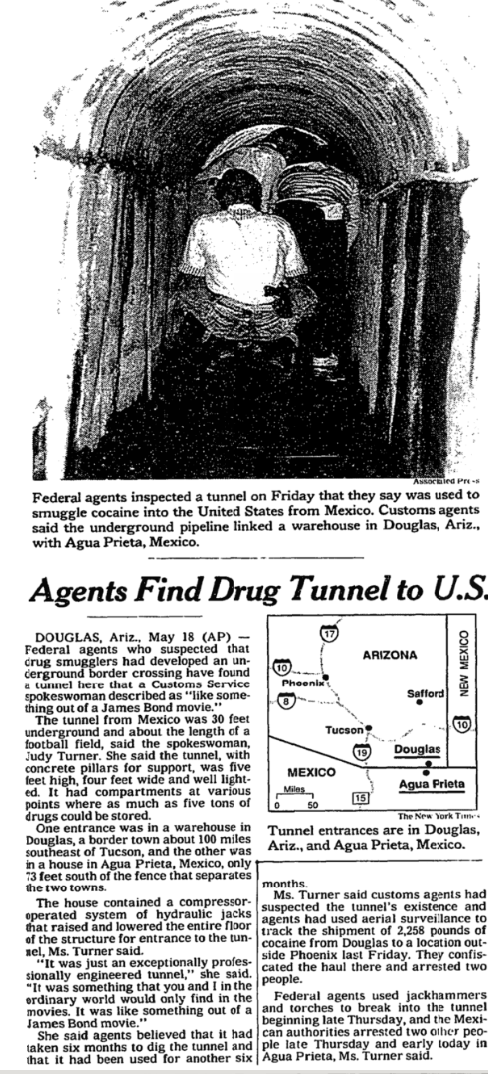

But gradually, suspicions grew about what exactly Camarena was doing in Douglas. He constructed a warehouse for the Douglas Redi-Mix business on his property, which was located about 100 paces from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Right across the border, just south of his warehouse, he bought another piece of land and built a sprawling, ranch-style home in a wealthy neighborhood of Agua Prieta.

As Camarena was building the home, neighbors noticed a large hole on the lot, which Camarena said was going to be a swimming pool. But over time, the supposed swimming pool began to fill up with dirt again. At this point — because both Douglas and Agua Prieta are relatively small and tight-knit communities — rumors were beginning to circulate.

People were saying that Camarena wasn’t just building a warehouse on the U.S. side and a nice residential home on the Mexico side. He was building some kind of tunnel between them. The dirt that slowly re-filled the swimming pool hole had apparently been dug out of a passageway that ran under the border.

U.S. Customs officials — first in Douglas and then in Phoenix — eventually received a number of tips from informants. They learned that Camarena was using the passageway to smuggle drugs from his home in Agua Prieta across the border to his warehouse in Douglas. But before law enforcement could go into the warehouse to search for the tunnel, they needed to establish that the smuggling was actually happening. They staked out Camarena’s warehouse.

Law enforcement eventually followed a flat-bed truck that they’d seen leaving the warehouse and trailed it to a property outside of Phoenix, where they conducted a raid. They seized over a ton of nearly pure cocaine, which had been transported inside a hidden compartment beneath the truck’s bed.

The Tunnel

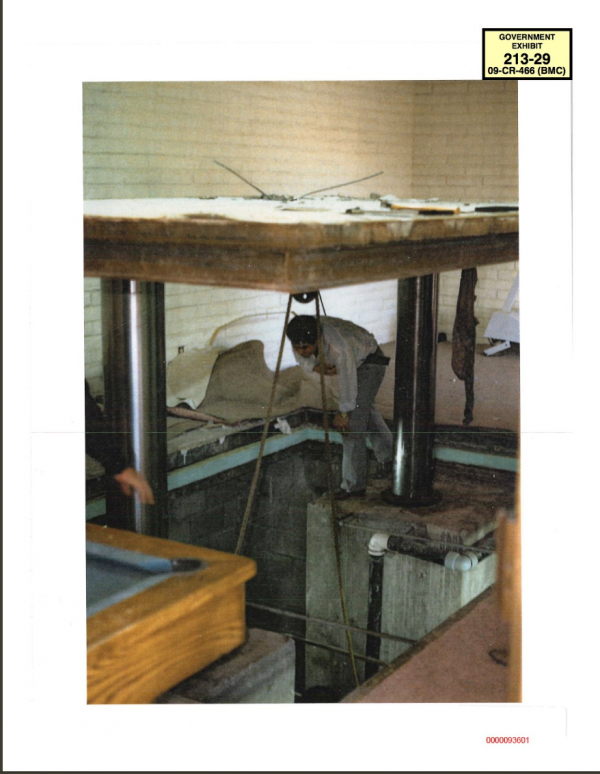

In May of 1990, law enforcement raided Camarena’s warehouse in Douglas and his home in Agua Prieta. First, they entered the warehouse, where they discovered one entrance to the tunnel underneath what looked like a drainage grate.

Then some of the agents headed over to Agua Prieta, where they were joined by the Mexican federal judicial police. They discovered that Camarena and his family had already fled. His house was empty.

The agents went into a recreation room with a pool table in it. When they pulled up the carpet, they could see there was something unusual about the floor. It looked as if there was a separate concrete slab underneath the pool table, like an enormous trap door.

The agents searched for a secret button or lever that might open it. Then someone turned a water spigot outside the recreation room — and the pool table rose up to the ceiling on huge hydraulic lifts, revealing the entrance to the tunnel below.

The tunnel was located about 30 feet underground. Once agents hit the bottom, there was a passageway about 270 feet long, four feet wide, and five feet high — just tall enough for a person to walk through, slightly stooped, pushing a wheeled cart full of bundles of cocaine.

The tunnel had concrete walls and a curved concrete roof. There was a ventilation system and rudimentary lighting. This was clearly a sophisticated engineering project. “Just the complexity to this whole tunnel was something that had been unseen before,” says U.S. Customs agent Terry Kirkpatrick, who was there the night of the raid and helped with the subsequent investigation. “And no one, I think, in the United States government — especially in law enforcement –realized anything like this ever existed.”

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman & the Architect

Currently, in New York, a massive trial is underway. Joaquin Guzman Loera, more commonly known as “El Chapo,” is one of the most powerful drug kingpins ever to face prosecution. He’s been accused of trafficking over 440,000 pounds of cocaine — along with mountains of other drugs — and for using murder, kidnapping, and torture to maintain control over a multi-billion dollar narcotics empire.

Under the leadership of El Chapo, the Sinaloa cartel became known for their creative smuggling methods — especially their tunnels. The one in Douglas, AZ became a kind of prototype for many tunnels afterward. And the person who oversaw that first tunnel’s construction was an architect named Felipe de Jesus Corona-Verbera.

Corona-Verbera denies his involvement in the tunnel scheme — and any other Chapo Guzman projects — but he was convicted of conspiracy and drug-smuggling in his own federal trial in 2006. A lot of what we know of him is based on testimony from that trial.

Back in the 1980s, before becoming the leader of a sprawling drug empire, El Chapo Guzman was a middleman in the cartel. He oversaw the smuggling corridor that included the Arizona border. And according to testimony by a former cartel member named Miguel Angel Martinez, the architect Corona-Verbera became connected with El Chapo to work on a number of projects.

Those projects included a number of residential homes, a farm with a zoo for Chapo’s exotic animals, and a grocery store with office space above it for the Sinaloa cartel. Each of these projects, according to Martinez, featured hiding places that could be accessed by hydraulic systems similar to the one that agents discovered in the Agua Prieta recreation room.

Corona-Verbera eventually moved to the Agua Prieta/Douglas area in 1989, with his wife and three kids. There, according to testimony by various contractors and laborers, he worked with tunnel front man Rafael Camarena, helping to oversee construction for the Douglas tunnel.

The Sinaloa cartel had picked the Agua Prieta/Douglas border as a tunnel site for a few reasons. For one thing, the cartel was already operating there. They had established networks and an established operation, and they’d already been moving drugs across the border above ground — mostly in vans and trucks equipped with hidden compartments.

According to testimony by Martinez, the cartel was able to move around three tons per month across the border using those trucks, but Guzman wanted to do it more efficiently. And to understand why he wanted more efficiency, you have to understand what was happening in an entirely different part of the U.S. in the early 1980s.

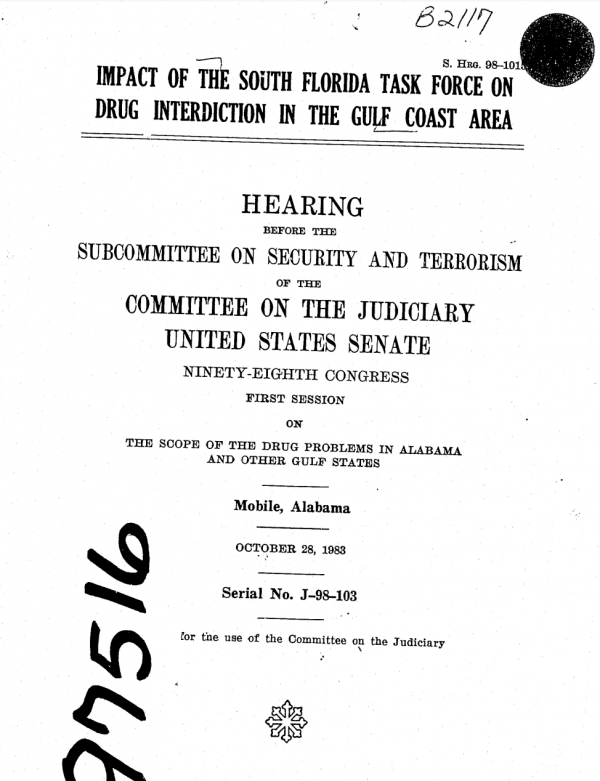

The South Florida Task Force

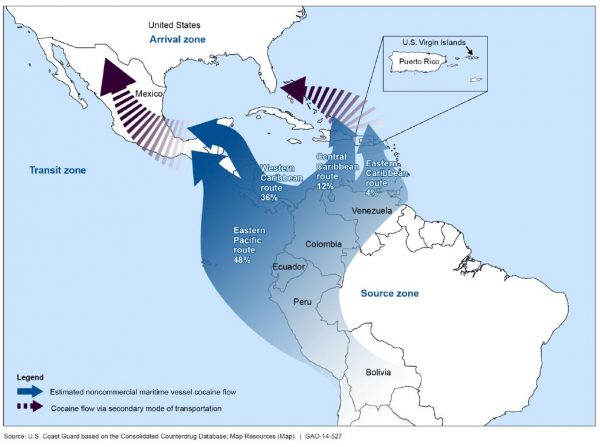

Back in the early 80s, most cocaine was coming into the U.S. not from Mexico, but from Colombia. The Colombian cartels preferred smuggling drugs into the country on boats and small planes, through cities like Miami. The drug trade was helping to fuel a surge in crime and so the Reagan Administration started something called the South Florida Task Force to fight it.

Back in the early 80s, most cocaine was coming into the U.S. not from Mexico, but from Colombia. The Colombian cartels preferred smuggling drugs into the country on boats and small planes, through cities like Miami. The drug trade was helping to fuel a surge in crime and so the Reagan Administration started something called the South Florida Task Force to fight it.

Reagan’s goals for the task force were ambitious. He said, “Our goal is to break the power of the mob in America and nothing short of it. We mean to end their profits, imprison their members, and cripple their organizations.”

But the reality is that the harder law enforcement makes it for smugglers to get goods across the border, the more money ends up getting pumped into the system. Militarizing the U.S. border — over many decades — hasn’t ended illegal trafficking. It’s just helped to professionalize it.

“The more you crack down on it, the harder it gets. The harder it gets, the price goes up. The more the price goes up, the more money is made. The more money is made, the more criminals want to do it. So the criminals then adapt to it and are richer and more powerful organizations,” explains journalist Ioan Grillo, author of El Narco.

When the Colombian cartels saw they were losing their product in drug busts in Miami, they didn’t stop smuggling. They just looked to a different border and new criminal collaborators. They turned to Mexico and made an agreement where they would pay the Mexican cartels to act as couriers, delivering cocaine to the United States.

As the U.S. government continued to crack down on cartels in Colombia, it eventually opened up new opportunities for the Mexican cartels to become more than just middlemen. They’d eventually come to dominate the entire cocaine supply chain.

The New Generation

With the rise of the Mexican cocaine trade, the Sinaloa cartel became even more powerful and more violent than it had been before. Over the decades, the drug war has wreaked havoc in Mexico, destabilizing the country, corrupting its institutions, and turning some of its most vulnerable people into asylum-seekers.

A lot of this violence was seeded back in the late 1980s. Not only because the cocaine trade was being rerouted through Mexico, but also because the cartels were undergoing an internal reorganization. A whole generation of older narcos was leaving the scene and a new generation was coming up. They were dividing up the old territory, and forging new alliances and rivalries. The new generation included El Chapo Guzman, an enormously creative, brutal, and ambitious narco.

And Chapo had some new ideas, like the tunnel in Douglas — which, according to some estimates, allowed the Sinaloa cartel to triple the amount of cocaine they were moving across the border.

Rumors of Local Corruption

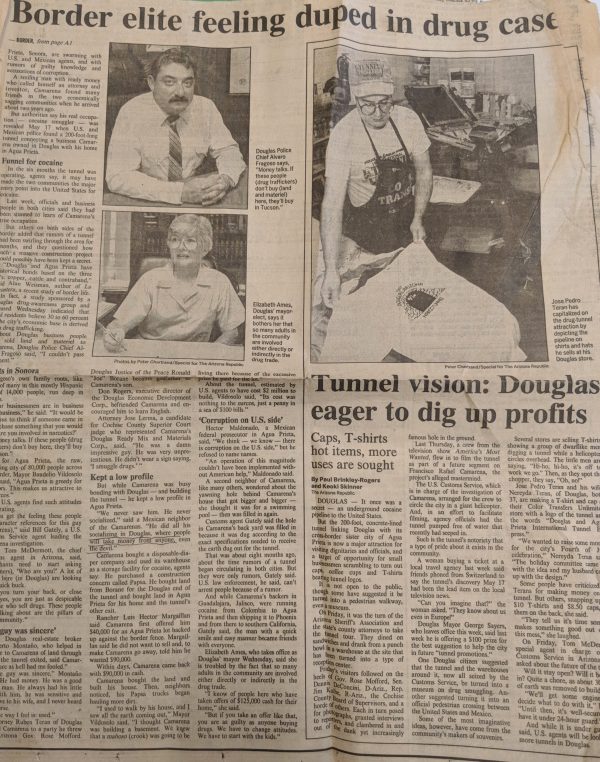

In addition to helping El Chapo make his name, the Douglas tunnel created a new kind of notoriety for Douglas, Arizona, which had formerly been a sleepy border town. Suddenly it was synonymous with the biggest drug trafficking story of the early 90s.

There were a lot of questions about how a smuggling operation of that magnitude could have happened without at least a few local collaborators.

In the aftermath of the tunnel’s discovery, journalist and juice shop owner Keoki Skinner got to work, writing a series of articles for his old newspaper — The Arizona Republic — which chronicled Rafael Camarena’s connections to various prominent people — not just in Mexico, but in Douglas.

No local officials or customs agents were ever charged, but the tunnel conspiracy left Douglas with a lingering reputation for corruption that has haunted it to this day.

The Spread of Tunnels

The Douglas tunnel was like a prototype. Even though it was eventually discovered, it was so efficient and effective during the time it was in operation that it paid for itself many times over. It was a successful experiment that proved the viability of underground smuggling.

Tunnels continue to be discovered along the Arizona and California borders, in places where the ground is soft enough for digging, but not so soft it will cave in. Some of the tunnels are pretty rudimentary but some, like the Douglas tunnel, are highly-engineered and sophisticated projects, with elevators and rail cars. A tunnel discovered in Baja, Mexico late last year included solar panels to power its ventilation and lighting systems.

Most illegal drugs actually come into the country through legal ports of entry. This fact, compounded by the existence of drug tunnels, are two reasons why President Trump’s proposed border wall probably wouldn’t do much to stop drug trafficking. But the U.S. government still sees tunnels as enough of a problem that they’ve funded tunnel-detection research and they’ve established Tunnel Task Force groups along the border. Those are a joint project of U.S. Customs and Border Protection and ICE. They exist solely to monitor, investigate, and prevent tunneling. But tunnels are notoriously difficult to detect. And they keep showing up.

Comments (1)

Share

I was a little let down with this episode because it neglected certain nuances on the so called ‘war on drugs’. My stomach turned when the show quoted policies by Ronald Reagan. You would think journalists like Gary Webb (who wrote The Dark Alliance series) and Charles Bowden did not exist. Bowden wrote the forward to The Dark Alliance compendium and also wrote Murder City: Ciudad Juárez and the Global Economy’s New Killing Fields (2010), among other fine books on the war on drugs. Here is Bowden in his own words: https://youtu.be/4DIrvg8RuMA