One of the times Gwendolyn Prebish tried to kill herself, she laid down on the tracks running behind her parents’ house in the Philadelphia suburbs. She survived three cars of a commuter train running over her body. She tried to take her life three times in 2016 alone.

Prebish, now 28, has struggled with mental health disorders since she was a small child. Currently held in jail and facing years in prison, she has finally regrown eyelashes after years of systematically pulling them out. Prebish has been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, anxiety, depression, and PTSD—struggles that, in recent years, have been compounded and soothed by her addiction to opioids.

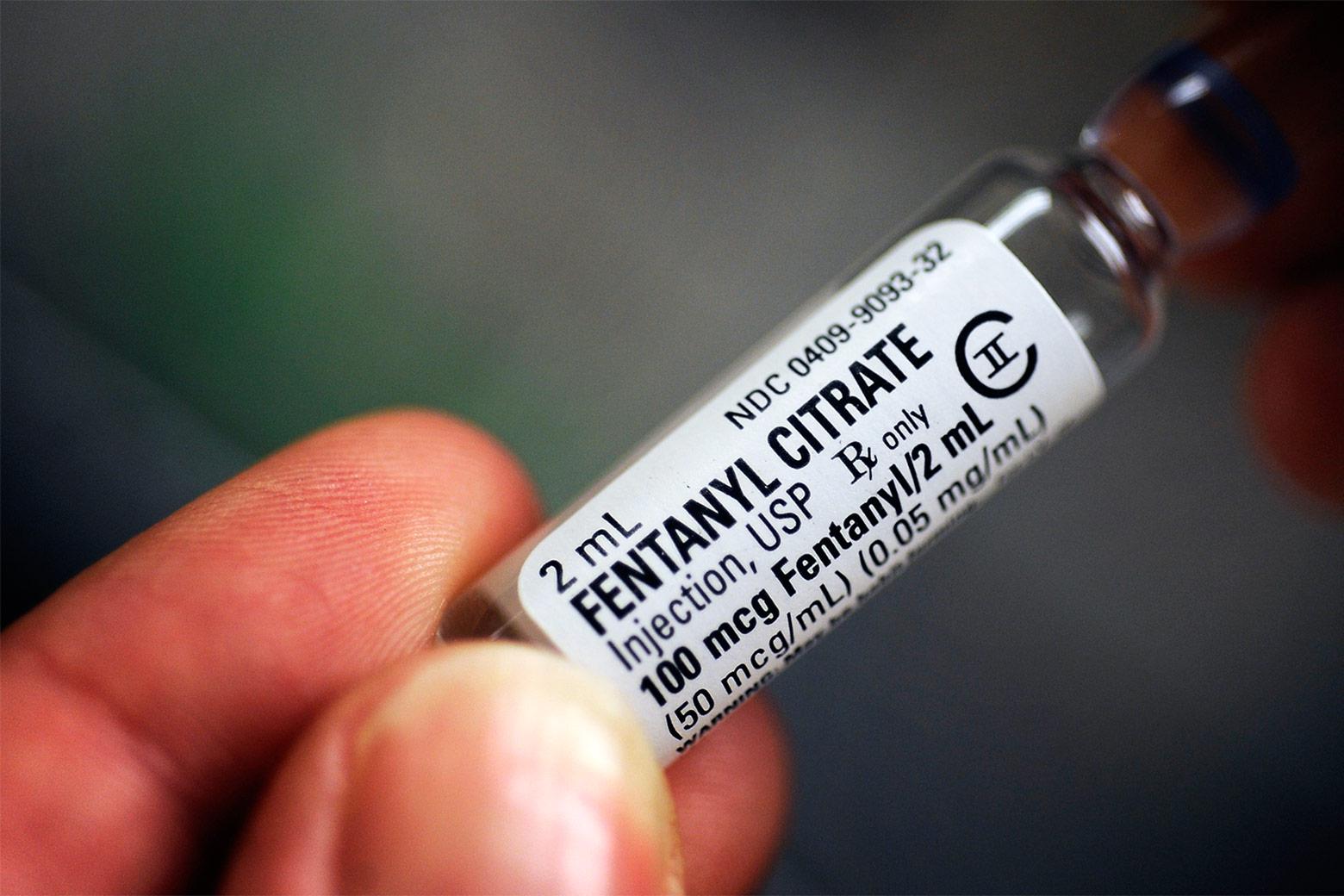

Today, she is facing a drug-induced homicide charge and could be sentenced to as long as 40 years in prison for providing Michael Pastorino, a fellow user in a Philadelphia suburb, with fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that ultimately killed him. Her parents, David and Lisa Prebish, recently greeted me at their home in suburban Montgomery County. Surrounded by family photos, they offered me an iced tea and recounted their daughter’s story.

“It’s a horrible fact that somebody died,” Lisa told me, apologizing for crying. But “she didn’t actually kill anybody … I feel like Gwen’s being prosecuted because she survived. Because she used the same thing that she gave him.”

Montgomery County District Attorney Kevin Steele sees things differently. Like a growing number of prosecutors nationwide, in response to fatal overdoses, he is charging the person who delivered the drugs, the purported “dealer” who is often also a fellow user, with a drug-homicide charge.

“You give a drug to someone and they die as a result of the drug, you are on the hook for drug delivery resulting in death,” Steele said in a statement after Prebish was charged. “Drug dealers need to know that they are killing people, and they will be held criminally responsible.”

As German Lopez reports at Vox, states have begun dusting off old drug-homicide statutes lately. And at least 16 have “passed laws in recent years that stiffened penalties for opioids painkillers, heroin, or fentanyl.” Most laws are targeted at drug sellers, a category that is expansively defined. The federal government and, according to a recent report from the Drug Policy Alliance, 20 states have drug-homicide statutes on the books, with a large number of charges filed from Wisconsin and Ohio to New Jersey and North Carolina. And legislators in at least 13 states introduced bills this year to create or heighten punishments for drug-induced homicide.

Joan Pastorino, Michael’s mother, met me at a diner in the Montgomery County suburb of Conshohocken and told me about the day her brother walked upstairs and found Michael in his bedroom. When he told her Michael was dead, she felt like she couldn’t breathe: “I can’t even describe the feeling.”

Joan had already lost a son to an opioid overdose. Six years before Michael died, he had been the one to find his brother, Andy, dead in his bedroom. That was not long after their father, Joan’s husband, died from a brain tumor. Now there was just Joan, her daughter, and the little girl that Michael left behind.

When the police arrived to Joan’s house on the evening of Nov. 6, 2016, they found Michael sitting at his desk holding a syringe in his left hand. They recovered his cellphone, two wax baggies stamped “Ferrari,” and two benzodiazepine pills. On Michael’s phone, they discovered text messages with Gwendolyn Prebish.

Michael had asked Gwendolyn if she could stop by his house with four “jawns,” Philly slang that can refer to just about anything. She agreed. Michael then asked her how long it would take, and asked her please not to forget about him. She responded to ask if he had $40. Close to 2:30 a.m., she texted again. She was about to pull up to his house with her dog in tow.

The next day, someone, apparently the police, texted Gwendolyn from Michael’s phone, pretending to be Michael. She replied by asking him if he had money for heroin—she says she needed money to drive into Philadelphia and buy a bundle that she could not otherwise afford. “Mike” told her that his friend wanted some, she wrote me from jail, and she began receiving texts from somebody who identified himself as Bill. Soon after, Gwendolyn sold a police source four blue wax baggies of the suspected heroin marked Ferrari in a sting. Prosecutors will likely point to this second sale to argue that Gwendolyn is not a sympathetic user but rather an incorrigible dealer. But according to Gwendolyn, it proves nothing.

The prospect of selling to a stranger had made her nervous. “I was real angry at first because they were blowing up my phone while I was working, and I didn’t want anyone except Mike knowing I snorted dope.” But she dreaded the looming prospect of going through withdrawal at work, so she went to hand over the baggies and got arrested.

A little over a week later, police received the lab results on the drugs Gwendolyn had in her possession the day of her arrest. It was fentanyl, the substance which, along with heroin, was determined to have killed Michael.

Michael’s mother Joan doesn’t know how she feels about the prosecution and knows little about Gwendolyn: “Do I feel it’s fair? Yes and no. I’m in between … I don’t want to judge. It is what the law says it is.” But she also knows that prosecuting Gwendolyn won’t do much good—it certainly can’t bring her son back. “They’re using her as an example,” she said. “I don’t believe it’s going to change anything.”

In response to an opioid crisis that has driven total drug overdose deaths in the United States to record highs, more than 64,000 in the last year for which there is data, police departments around the country have retooled their response to opioid overdoses to treat each incident more like a crime scene. Prosecutors have been increasingly filing drug-homicide charges in response to overdoses—perhaps to help show that they are doing something about a problem that seems intractable to many.

In 2011, the Pennsylvania Legislature altered the law to remove the requirement that prosecutors prove that a dealer intended harm to win a conviction for drug delivery resulting in death. According to an analysis of court data by the Scranton Times-Tribune, prosecutors statewide filed 317 cases of drug delivery resulting in death from Jan. 1, 2011, through Sept. 30, 2017. The number per year has ticked up steadily according to this data—from 41 in 2015, to 76 in 2016 to 126 through September 30 in 2017. Of the 189 that had been resolved as of the time of their reporting, roughly 43 percent resulted in convictions for the charge, with another 57 percent resulting in convictions on lesser charges, including involuntary manslaughter and possession with intent to deliver a controlled substance.

Philadelphia has long been a place where a large number of people use heroin. But in recent years, like much of the rest of the country, opioids have spread through the suburbs and to rural areas. The causes are complex but are no doubt related to the increased prevalence of pharmaceutical opioids like OxyContin. Many users who started with prescription pills have since transitioned to heroin bought on the street, thanks in part to the crackdown on prescribing. Beginning in 2013, the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl, often about 40 times stronger than heroin, surged into the illicit market. Ironically, the scourge of fentanyl that law enforcement is trying to wipe out is likely a result of prohibition: The illicit drug market incentivizes dealers to pack the strongest potency into the smallest quantity to maximize profits and avoid police detection; cutting heroin with fentanyl or cutting fentanyl with an inert substance allows for dealers to increase profits with a drug that can be easily smuggled by mail.

Despite all the pledges from politicians and the generally sympathetic portrayal of the crisis’ often white victims, social services and treatment remain in short supply. Police, prosecution, and prison time, on the other hand, are widely available. The prosecutions are just the latest crackdown in a drug war that has only ever exacerbated the problem, said Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University.

“The opioid crisis, first and foremost, is an indictment of decades of failed drug policy,” said Beletsky. “We have consistently invested in punishment and repression, while our health and social safety nets have crumbled. Overtime, crackdowns and incarceration supposed to dismantle drug trafficking organizations have made illicit drug supplies cheaper, purer, and more readily available. Doubling down on those efforts will only add fuel to the fire.”

Not so long ago, it seemed to many that the drug war had reached its breaking point. After locking up so many people for so long, leaders across a political spectrum that had once marched in lockstep behind law-and-order policies were having grave reservations. Longtime leftist critics of the country’s gargantuan prison system and libertarians condemning government overreach suddenly had their message amplified by evangelicals preaching redemption and fiscal conservatives decrying wasted taxpayer dollars. Black Lives Matter directed a harsh spotlight on the system and Democratic centrists like Hillary Clinton disavowed old positions that had suddenly gone out of fashion. President Barack Obama, after doing little initially, commuted a record number of drug-related sentences. Several states have legalized recreational marijuana.

Today’s opioid crisis is diverse in reality but is often portrayed with a downwardly mobile white face. Many observers argue that it has received a sympathetic response from politicians and the media, sympathy that was never afforded to the black people who were the face, though not the entire reality, of crack use in the late 1980s and ’90s. Today, under the banner of public health, some public officials are pushing to get the overdose-reversal drug naloxone into the hands of first responders.

Legislatures have passed good Samaritan laws that offer legal protections to people who call 911 in an overdose emergency.

And incarceration rates, both overall and for drug crimes in particular, have fallen. Nationwide, the number of people in state prisons whose most serious conviction was for drugs has declined even as the opioid crisis took off, from 251,000 in 2000 to 206,000 by the end of 2014, the last year for which we have data, according to John Pfaff, a professor at Fordham Law School and an expert on mass incarceration. And between 2010 and 2015, even as opioid and heroin abuse and deaths rose, the overall U.S. prison population continued to decline—the opposite of the mass incarceration that accompanied the crack crisis of the 1980s. Similar trends appear to hold in Pennsylvania, whose prison population has fallen while the number of people admitted to prison on drug charges has also declined in almost every county.

Of course, the crack and opioid crises manifested in very different ways. One difference is that while opioids are far more deadly, their lethality involves far less interpersonal violence (though this is not, of course, true for Mexico, where prohibition-enabled drug production and distribution, and the war against it, have been extraordinarily violent). During the height of crack crisis and panic, the homicide and overdose rates grew side by side. Today, gun violence remains at historic lows while overdose rates have hit historic highs. Yet the response to the opioid crisis demonstrates that the punitive logic underlying the drug war retains a powerful hold.

Furthermore, most of the de-carceration we have witnessed in the U.S. has taken place in urban counties. Rural counties have grown more punitive—and even though rural areas don’t have higher fatal overdose rates than cities, they have seen their fatal overdose rates increase more rapidly. A 2016 analysis in the New York Times found that between 2006 and 2013, more populous counties saw the rate of prison admission drop, with the sharpest declines in the largest counties, while more sparsely populated counties saw their admission rates rise. Since 2013, according to Pfaff, Pennsylvania has seen a similar trend.

As the crisis spreads, prosecutors are taking a harder line: Law enforcement, it turns out, is still the front line of dealing with any perceived social ill. The very newfound sympathy for white drug users may perversely reinforce a carceral approach towards “dealers”—but in many cases, these dealers are just fellow users cobbling together cash for their own habit. Either way, punitive approaches have failed to keep increasingly potent drugs from killing ever-growing numbers of people. In fact, as Beletsky argues, they have done the opposite. And laws treating users who sell drugs as murderers could make it less likely that people will call 911 to report an overdose, leading to even more deaths.

Most everyone that I interviewed for this story struggled to make sense of the opioid-induced carnage underway and what role law enforcement can, and should, play in combating it. The law enforcement crackdown offers some families of the dead the small comfort of a narrative with a victim and villain. But the characters often don’t quite fit the part.

After their daughter’s arrest made the news, the Prebishes thought they would be ostracized, even demonized. But co-workers and even acquaintances approached them, recounting their own family members’ struggles with addiction.

It seemingly could have gone the other way, with the roles of Gwendolyn and Michael reversed. Indeed Gwendolyn says that Michael sold her heroin on more than one occasion, but it was her mugshot splashed across the evening news without any meaningful context. That picture, of a distraught and strung-out looking woman, bore no resemblance to the person in the family photographs that her parents showed me. If it had been Michael who had sold the drugs, and their daughter who had died, Gwendolyn’s parents say they would want him to get help.

“I gotta be honest with you,” Lisa Prebish, her mother, said. “A lot of kids we know are dead.”

Gwendolyn first encountered opioids when they were prescribed to her in the wake of months of horrific violence at the hands of a boyfriend. The result of that abuse, she writes, included cracked ribs, a collapsed lung, cracked discs, chipped vertebrae, and a torn pectoral muscle, which her doctor reported he had only witnessed in weightlifters and football players. The prescribed Vicodin made it possible for her to work as a carriage driver in Old City Philadelphia, and to work with horses and ponies at the Elmwood Park Zoo. But they also, she writes, “helped numb all of my sad and anxious feelings. The opioids put me in a state of euphoria and I finally felt I was good for something.”

“I was numb from all of my feelings for a while by taking medicine,” Gwendolyn writes me, recounting her struggle with mental illness and her reluctance to confront her demons. “I also thought I was too weird and crazy for the world and they would just lock me away.”

When her prescription ran out, she found a friend with one. When that friend died from an overdose, she didn’t know how to live anymore. She discovered heroin. It was cheaper and better. She would buy a bundle at a time to save money on what she came to consider to be her “medicine.” Soon, Gwendolyn realized that she would get dope sick without it and be unable to work. All around her, overdoses were killing friends. But she couldn’t stop using.

“That was when I met Michael Pastorino,” she writes. “He was a stranger that asked me out on a date when he saw me at the bank.”

Gwendolyn gave Michael her number. He contacted her and told her he was a “well-known drug dealer.” He would be, she thought, a useful hookup if she ever needed heroin. He sold her heroin a few times, she says, and sold to others as well. But he was not really a drug dealer. He turned out to be more of an addict. Like her.

“A couple times he would contact me saying how sick he was and would ask me if I had an extra to help him,” she wrote. “Usually I would just ignore him, but sometimes I felt bad because I knew how much it sucked to withdrawl [sic].”

Prebish’s lawyer, Jonathan Sobel, had petitioned for her case to be diverted to a behavioral health court: If anyone has the mental health history to quality, it would be Gwendolyn. Prosecutors, however, opposed the petition, he says, and it was rejected. The Montgomery County district attorney—the same office that made sure to issue a sternly worded statement to local media after Gwendolyn was charged to be featured alongside an unflattering mugshot and video of her perp walk—declined to answer questions about why Prebish merits such harsh punishment, saying that they don’t comment on pending cases.

Some parents, like Michael’s mother, Joan Pastorino, are torn about the best way to achieve justice for their loss. Others feel the situation is much more clear cut. Peggy Eschenburg, for example, knows that the prosecution of the two people who supplied the fentanyl that killed her son, Justin, won’t bring him back. But it does offer her some comfort.

“Justin was not an addict,” said Peggy, over pizza and chicken wings in their kitchen in the small town of Trumbauersville, which sits amidst a patchwork of exurbs and still-undeveloped countryside between Philadelphia and Allentown. “That’s what makes this, like I said to you, so much more horrible.”

Justin had hurt his back at work, his parents say, and his friend Kyle Wireman had offered him a Percocet for the pain. It turned out to be fentanyl.

According to Tom Gannon, a Bucks County deputy district attorney, the two pills that Kyle gave Justin were a $50 down payment on an outstanding loan. On Nov. 2, 2015, Kyle took one pill orally. Justin ground his up and snorted it. After Kyle left, the two exchanged texts, which Gannon read: “whatever the fucking thing was,” said Justin, “it worked;” “I know right, lol,” Kyle responded. The last text was sent at 7:05 p.m. Justin’s father found him dead the next day. Justin also had a cocaine metabolite in his system, says Gannon.

“He didn’t check up on him. And he should have,” said Gary, Justin’s father, referring to Kyle. But nearly two years later, his feelings about it were complicated. “I do kind of feel bad for Kyle too at this point. … We just thought he was a monster. We just thought, you know, he didn’t really care or anything.”

Justin’s parents think five years, the minimum Kyle was initially sentenced to after pleading guilty, is the right amount of punishment. They think the woman who had initially sold the pills to Kyle, Brianna Nicole Burns, is the real monster who killed their innocent son. Justin’s family wanted her to go away for a long time—even longer than the nine to 18 years she was sentenced to.

“I’m hoping she gets a lot more [time] because she clearly has no morals, no”—said Justin’s sister, Lauren Zepp, before Peggy interjected: “Empathy.” Zepp continued: “No goals in life.”

“She doesn’t seem to have any remorse,” said Peggy. “She can rot, she can go for 35 years. That’s fine with me.”

Burns, now 24, was sentenced after pleading guilty to drug delivery resulting in death and other charges. Gannon says that she also sold the supposed-Percocet-but-actually-fentanyl to a man, William Grzyminski, whose wife found him dead in the garage. In that case, Burns was convicted of reckless endangerment because, says Gannon, his death could not be exclusively linked to the fentanyl. She also pleaded guilty to charges stemming from other incidents when she allegedly sold marijuana, methamphetamine, and oxycodone to police.

Brianna’s ordeal began when police tracked down Kyle after finding the texts on Justin’s cellphone. It was Kyle who then set Brianna up to sell drugs to a cop. As Gannon put it: “She continued to sell controlled substances even after she killed two individuals.”

But selling some on the side, Brianna writes from prison, was “how I supported my [Percocet] 30s habit … I sell one,” then “right away that $ bought me one to do. I did not sell to be a dealer and make $.” Today, she struggles to understand why the police decided it was Kyle who was less culpable. (In September, his already much shorter sentence was significantly reduced after he requested that a judge reconsider.) “Because I’m addict, he is addict; meaning we know were [sic] to get drugs! And as addicts we do the dirty work for the dealers so it pays for our drugs so us addicts don’t get sick!”

Burns is trying to come to grips with spending most of her early years as an adult in prison. Burns told me that she wishes the deceased’s families could see that she wasn’t the heartless person prosecutors made her out to be. She “broke down in tears beyond tears,” she wrote, telling detectives everything she knew “hoping to help”—perhaps unwisely in retrospect.

“Why did the honesty I gave kick me in the ass? … I know my wrongdoings, I am not innocent here but am I this monster they labeled me as?” Brianna says that her problems began as a child, after her mother’s boyfriend moved in to the house. He suffered from alcoholism and abused her mom, prompting frequent police visits to their home. Drugs and alcohol provided numbness.

Her father, Robert Burns, had no money, no home to mortgage, that might have allowed them to hire a high-powered lawyer. He struggles to understand why his daughter is a villain and Justin a victim. And having lost an infant who was killed while in a babysitter’s care in 1990—who was charged with and acquitted of murder—he doesn’t believe that the justice system delivers justice to people without the means to pay for it.

“The laws are not set up to handle the epidemic that’s going on,” says Robert. “And the problem is the counties and the states are getting pushback because of how bad it’s getting and they want to show that they’re doing something to curb it. So they’ve twisted the laws around to arrest people like my daughter and use them as examples of putting a dent in the drug situation when it’s just really not true. But to an outside person it looks like, ‘Hey they’re doing something, look they put another one away.’ ”

Gannon, the prosecutor, concedes that Brianna Nicole Burns is “not a titan of industry. She’s not someone making money hand over first. And she certainly was a drug user.” But he doesn’t believe that she was truly remorseful and has convinced himself that there’s a distinction because she didn’t absolutely have to sell drugs to survive.

As for Peggy Eschenburg, who lost her son to fentanyl, she is far from confident that the prosecutions will do anything to keep people safe from overdoses. But at this point, having lost two children—a daughter in a car crash in 2002, and then Justin—it’s not her concern. “I definitely wanted justice for my son because of who he was as an individual. Yes. As far as society, like I said: I don’t really care. I’m just one individual that’s just had enough.”

Chris Leupold strikes a discordant note, sitting in his parents’ kitchen about 30 miles to the southeast in Bensalem, a heavily white working-class Philly suburb in Bucks County. Over a tall boy of beer, he explains that he finds the prosecution of Jomar Eric Rodriguez, the man who was convicted of indirectly selling his brother Jay a fatal dose of heroin, to be an absurdity.

“It’s not the kid’s fault, man,” says Chris, in a gravelly voice. “It’s doing nothing to help the situation. It’s not gonna stop anybody. That’s just an asinine way to look at it. Them big guys, they don’t care. ‘Oh, one of the little guys got taken down again. We’ll maybe throw some money on his books while he’s doing time. And we’ll replace him that next day with another guy.’ ”

It was a young woman that sold the heroin, in packets labeled “Slow Motion,” directly to Jay Leupold, according to former Bucks County Deputy District Attorney Dan Sweeney. After Jay used it, he sent that woman a Facebook message reporting that it was “fantastic.” Then, Jay hung out with his mother for a while watching television before going upstairs for a bath. While in the bathroom, he shot up the heroin again and died on May 7, 2016. His mother, Susan Leupold, found him dead in the morning.

Police quickly located the woman, whose lawyer declined an interview request on her client’s behalf, who had sold Jay the heroin. She agreed to work with them and set up Rodriguez, a dealer in Philadelphia, for three drug buys. During one buy, says Sweeney, the woman showed Rodriguez Jay’s obituary on her cellphone.

“Oh, he died? Oh shit,” he said. “Damn, that shit that good?” Heavily tattooed and the only person amongst the deceased and defendants who is not white, he perhaps better fit the stereotype of “drug dealer.” He was sentenced to six to 20 years in prison.

Still, Chris doesn’t blame him. He blames his own brother, and he blames the young woman who sold him the heroin, a woman with whom he already had a complicated relationship. (A few years ago, Chris says, she had set him up to sell Ritalin in a police sting, which resulted in Chris spending nearly a year in jail for violating probation.)

Today, that young woman is awaiting trial on possession and conspiracy distribution charges that could land her in prison for 15 years, according to her lawyer—but that might not, given how she cooperated in Rodriguez’s prosecution.

“Listen, I don’t get the law,” says Chris, who moved back in with his parents several years ago. “Because the law don’t want the truth.”

Rodriguez, who did not respond to a letter mailed to him in prison, was convicted on drug dealing charges but acquitted of the drug-delivery resulting in death charge. Two other empty bags had been found in the bathroom with Jay, says Sweeney, and it couldn’t be established beyond a reasonable doubt which baggies had killed him.

As far as Chris can see, the police are just out to make busts that do nothing to stop the crisis raging around them, but Chris knows that his parents disagree.

“The guy’s a drug dealer,” says his father, Bud Leupold, dragging on a cigarette at a house that he and Christopher are remodeling for resale. “Dude, you got a drug dealer and you got a death. Not guilty? Come on, man.” Like many of the houses they work on, it’s a foreclosure. Unlike two prior houses, he says, it had not belonged to drug dealers.

Still, he concedes that the conviction won’t do much of anything to stop the crisis. Jay had cycled in and out of addiction for years, stealing from his parents, getting booted from the house, and was ultimately dumped by a longtime girlfriend.

Identifying and punishing individual culprits for selling illicit drugs that they used themselves might make people feel better. But in reality, we have spent decades pursuing a grand experiment, incalculably costly in both lives and dollars, that promised that police and prisons could save people from drugs, and never succeeded. The criminal justice system is designed to deal with victims and perpetrators. But with the opioid crisis, the two are often indistinguishable. The dividing lines that have helped people make sense of things no longer do. Perhaps they never really did.