US loses former Guantanamo inmates after Donald Trump shuts office tracking them

- At least one of the inmates has vanished in a terrorist-held part of Syria

The Trump administration closed a diplomatic office designed to keep track of released Guantanamo inmates and make sure they didn’t return to their insurgencies.

And now the US government has lost track of several of them, including one who has returned to a terrorist-held part of Syria, a Tribune News Service investigation has found.

Guantanamo Bay prisoner released in surprise Trump U-turn

The Obama administration created the office of the Special Envoy for Guantanamo Closure with a mandate to negotiate and follow up on prisoner releases. But US President Donald Trump’s State Department emptied the office to underscore his campaign promise to keep open the US military prison in Cuba, which today has 40 detainees.

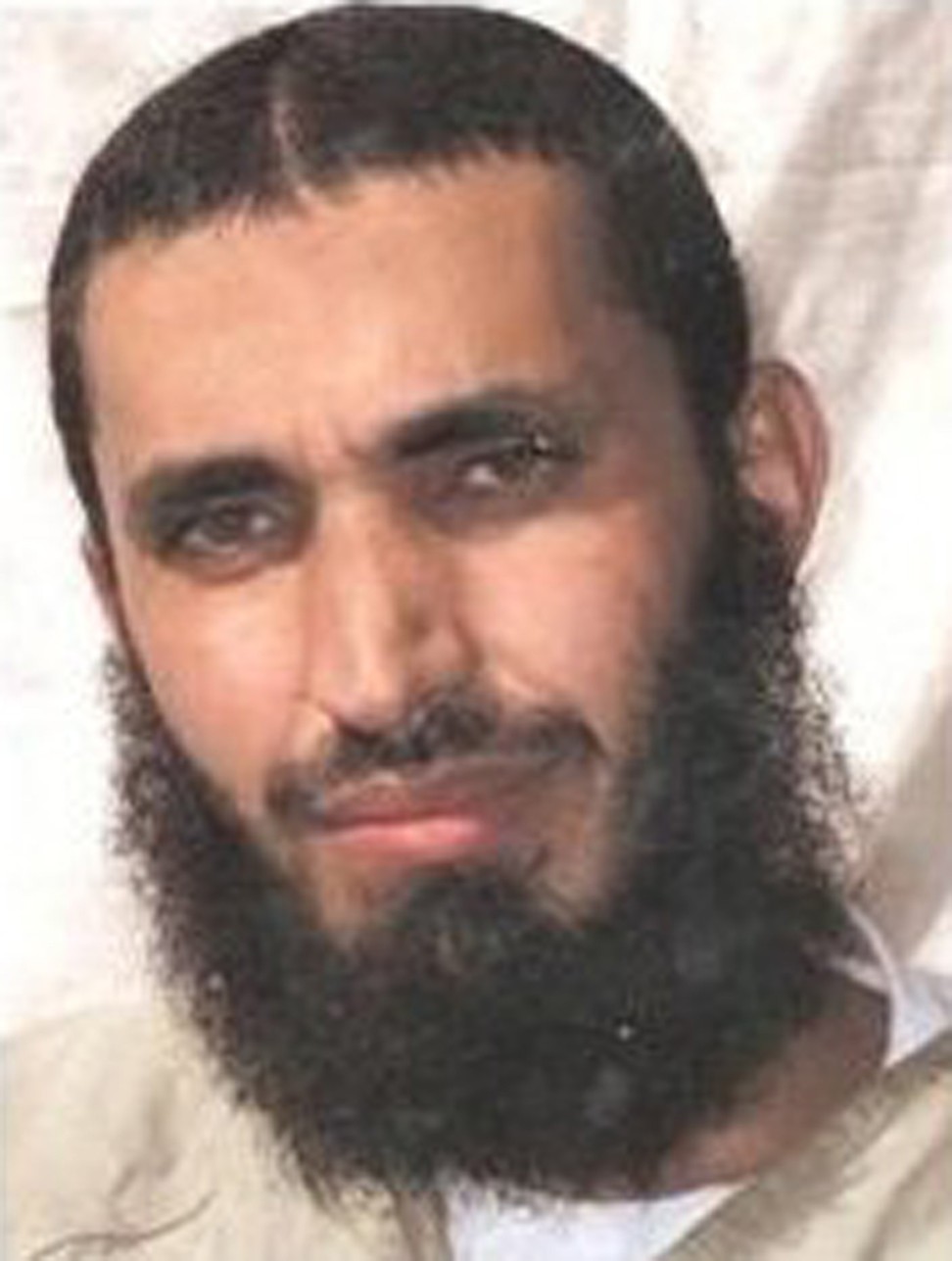

One of the most glaring examples is that of former captive Abu Wa’el Dhiab, a Syrian who vanished from Uruguay last summer. Jose Gonzalez, executive adviser to Uruguay’s Interior Minister, told McClatchy that Dhiab walked across the Uruguay-Brazilian border, took a bus to Sao Paulo and caught a flight to Turkey. The Turkish Embassy in Washington said a search of Interior Ministry records found no evidence that he had arrived there.

Dhiab has been detected in south central Turkey where he has slipped in and out of the rebel held Idlib province, controlled by the al-Qaeda affiliate Nusra Front, according to a Syrian diplomatic source, citing Syrian intelligence. His mother is receiving medical care in Turkey, the Syrian said.

Dhiab fled Syria in 2000, according to both his leaked US intelligence profile and the Syrian diplomat. He kept company with jihadists before his 2002 capture in Pakistan and transport to Guantanamo. While there, he was an incessant irritant to his American jailers – a committed hunger striker who underwent painful forced feelings to protest his detention without charge.

Guantanamo’s indefinite detainees ‘will die there unless court steps in’

An aide at the House Foreign Affairs Committee, who granted a briefing on condition of anonymity, called Syria “the worst place for an angry (former detainee) to turn up.”

Dhiab’s disappearance is a perfect storm of a troubled Obama administration resettlement deal that went off the rails at a time when the State Department had no meaningful monitoring of detainee releases.

US intelligence and State Department officials would not discuss Dhiab’s whereabouts. Spokesman Alexander Vagg said Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently assigned the Counterterrorism Bureau to start addressing “any issues stemming from the arrangements made between the Obama administration and foreign partners regarding the resettlement of former Guantanamo Bay detainees.”

The last State Department envoy for the closure of Guantanamo, Lee Wolosky, said he had been receiving phone calls from foreign envoys and other concerned people – even though he left government at the close of the Obama administration – because “they have no one to talk to in the US government.”

He described the disappearance of Dhiab as particularly worrisome.

He was not only damaged but he was someone who I thought was dangerous

“We worked pretty hard to make sure that he stayed in Uruguay in the Obama administration,” he said. During that time, however, Dhiab found his way to Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela, and at one point on a flight to South Africa, only to be sent back to Uruguay through US intervention. In 2017, he also used a forged passport to fly to Morocco, which returned him to Uruguay. “He was not only damaged but he was someone who I thought was dangerous,” Wolosky said.

Syria is of particular concern because that’s where a former Guantanamo prisoner could return to the fight. The US has about 2,000 troops there, according to Pentagon spokesman Commander Sean Robertson.

In Uruguay, Dhiab never really settled, unlike the other five former detainees who were sent there with him. He organised protests outside the US Embassy in Montevideo and resumed his hunger strikes there to protest separation from his family.

Canada to pay US$8m to former Guantanamo child prisoner

The most recent figures from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence say about 30 per cent – or 222 former Guantanamo captives – have or are suspected of having returned to militant or terrorist activities after leaving the wartime prison. Of those, 196 men were among the 532 captives repatriated by the Bush administration in massive transfers, mostly to Afghanistan, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

The Obama administration took a different approach to detainee transfers. It negotiated deals with 30 countries to take in men who could not be sent to their home countries because of domestic instability or poor human rights records, generally in small numbers and with specifically fashioned social welfare arrangements. Terms of the deals have never been made public but Obama administration officials said the host countries would provide housing, living stipends and language classes if necessary to help them adapt. As a rule, the host countries agreed to not provide them travel documents for their first two years.

Oman receives 10 prisoners from Guantanamo Bay

The Obama administration released nearly 200 prisoners – nine returned to the battlefield and another 17 are suspected of doing so, according to the ODNI’s Counterterrorism Centre.

By the time Trump took office, the State Department special envoy office had sent 142 men to 30 nations for rehabilitation, resettlement or safe haven – and another 52 back to their homelands. Most of the resettled captives went to Europe, Africa and Persian Gulf nations.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson closed the office and assigned the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs to handle any problems that arose in the transfers – a move House Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Ed Royce, a Republican, protested as ineffective, according to the committee aide. Then, deals with some third countries began to unravel.

In April, Senegal abruptly sent two Libyan former detainees back to Libya, declaring it was done with its obligation to host them. One of them, Awad Khalifa, resisted repatriation out of fear. The two vanished, according to Khalifa’s US attorney, Ramzi Kassem.

Of five detainees sent to Kazakhstan in December 2014, just two remain. Their lawyers said the five felt isolated with no prospects for assimilation in the non-Arabic speaking society. One, a Yemeni, died of kidney failure from a long-standing illness soon after he arrived. Then, after the US resettlement office was shuttered, two Tunisians relocated to Mauritania with the assistance of the International Red Cross, said attorney Mark Denbeaux. State Department officials would not comment on whether they were even aware of the transfer.

Twenty-three men sent to a rehabilitation programme in the United Arab Emirates in 2016 have disappeared into what their American attorneys now believe to be a detention setting.

By scattering the former detainees to 30 nations, the Obama administration cast it as a concerted effort to give men who had lost a decade or more at the US military prison in Cuba a new chance in a new country. And not every deal had a bad ending.

Abu Zubaydah, waterboarded 83 times by CIA then hidden from view for 14 years, pleads for freedom

It sent 18 former Uygur prisoners – former Chinese citizens whom a federal court found unlawfully detained by the US military – across the globe to get them out of Guantanamo. Six were sent to the East Pacific nation of Palau, and moved on to Turkey with advance notice to the State Department. Two left El Salvador in 2013, also likely for Turkey, with notice to the United States.

But the House Foreign Affairs Committee aide said the Obama administration, in its haste to try to empty Guantanamo prison, set up resettlement deals in countries with no capacity to keep an eye on them. Lawyers, and some former captives, said some of the countries were bad matches for Middle Eastern men.

Yemeni Abdul Malik Wahab al-Rahabi, for example, found life in Montenegro culturally incompatible.

The Obama administration sent him and another Yemeni there in 2016. He described it as “a beautiful, beautiful” welcoming country, so much so that they helped him bring his wife and teenage daughter to join him.

But the language was too hard for his daughter, making it impossible for her to further her education. And his wife missed the company of fellow Arabic speakers.

He arranged to move to Sudan, where he was reached him by telephone. Montenegro’s two-year stipend and housing was running out, Rahabi said, and he couldn’t find a job. He had hoped to make a living by selling artwork he took with him from Guantanamo, but his Twitter marketing campaign didn’t work out.

In Sudan, Rahabi said he has found other Yemenis who can’t go home to the civil war torn nation. “Life here is so difficult,” he said, explaining he has yet to find work – or sell the art he took from Cuba to the Balkans to Northeast Africa. “But it is good for another side for me and my family. Same language, same culture, it’s easy to get close with the people, buy something, go there and there and speak with everyone.”

Neither Trump State Department officials nor US intelligence would comment on whether they were aware of Rahabi’s move.