When we first meet Alex Levy, the morning show host played by Jennifer Aniston, she’s attempting to wake up and begin the regime of stardom at 3:30 a.m. She starts the coffee and opens a Red Bull, then fumbles to the treadmill, the world still pitch-black around her, and attempts to walk while resting her head on the control panel. She places under-eye masks on her dark circles, scrutinizes her face, jade rolls, and scrutinizes again. She gets into the elevator and rests her head back — exhausted. As she gets in the black car that takes her to the studio, her face purses in annoyance as they drive past a giant billboard of her smiling.

It’s the first hint of what The Morning Show, now streaming on Apple TV+, will spend the season unpacking: There’s the composed, cheerful, public Alex, and the deeply exhausted, deeply pissed-off person behind the mask.

And all this is before the show’s executive producer, Chip (Mark Duplass), tells Alex that her cohost, Mitch (Steve Carell), has been fired for sexual misconduct. As he quietly explains that Mitch had been under investigation by HR for multiple offenses, she explodes. “You knew about this and didn’t tell me?” she yells. “What am I, some fucking PA from Idaho who doesn’t need to know what’s going on?”

“Oh fuck you, Chip,” she spits at him after he attempts to explain himself. “Fuck you. ... This affects me. My on-air partner, my TV husband, is a sexual predator now? What part of you thought that I should not be involved in this conversation?”

And yet she still has to “bring the news to America.” Sitting in the makeup chair, preparing her opening monologue, she notices Mitch is calling. She very calmly silences the phone, and then, with a burst of fury, bashes it into the drawer in front of her.

By the time Alex walks onto the morning show stage, all that anger has been temporarily, necessarily swallowed. She delivers the news of Mitch’s firing with strength and grace, a picture of self-possession and concern. Like everyone else on that soundstage, she knows that anything less would lead to endless critique. One of the network heads remarks, “It’s too bad we can’t always throw a crisis at her. It turns her lights on.”

The Morning Show, costarring the equally fed-up Reese Witherspoon, is at once a manifestation of and reckoning with women’s middle-aged rage. As showrunner Kerry Ehrin put it, “It’s almost like this orchestral finale — this huge noise and sound all these emotions that have just been stuffed down in these women for all these years, you know?”

It’s not that this rage is new. It’s always been there, in various, and variously sublimated, forms. There have just been so few opportunities for it to be listened to — at least within the mainstream — because there have been so few mainstream productions that even take older women, let alone their anger, seriously. But The Morning Show, for all of its unevenness, also serves as a meta-textual commentary on the fatigue of decades of being a woman in the public eye. This is a fine show about morning television, and a not-always-successful show about #MeToo. But it’s also a very interesting show about Jennifer Aniston.

“For the record, I am not pregnant,” Jennifer Aniston wrote in 2016. “What I am is fed up.” Because she didn’t have social media, Aniston had decided, after years of nonstop gossip about her romantic life, to write an editorial for HuffPost, lambasting the “sport-like scrutiny and body shaming that occurs daily under the guise of ‘journalism,’ the ‘First Amendment’ and ‘celebrity news.’”

It’s a fascinating, insightful piece — at one point she wonders, “If I am some kind of symbol to some people out there, then clearly I am an example of the lens through which we, as a society, view our mothers, daughters, sisters, wives, friends, and colleagues.” But it’s also shot through with palpable rage, and not just in the quotes she repeatedly places around the word “journalists.” “The sheer amount of resources being spent right now by the press trying to simply uncover whether or not I am pregnant (for the bajillionth time…but who’s counting),” she writes, “points to the perpetuation of this notion that women are somehow incomplete, unsuccessful, or unhappy if they’re not married with children.”

The Morning Show, for all of its unevenness, also serves as a meta-textual commentary on the fatigue of decades of being a woman in the public eye.

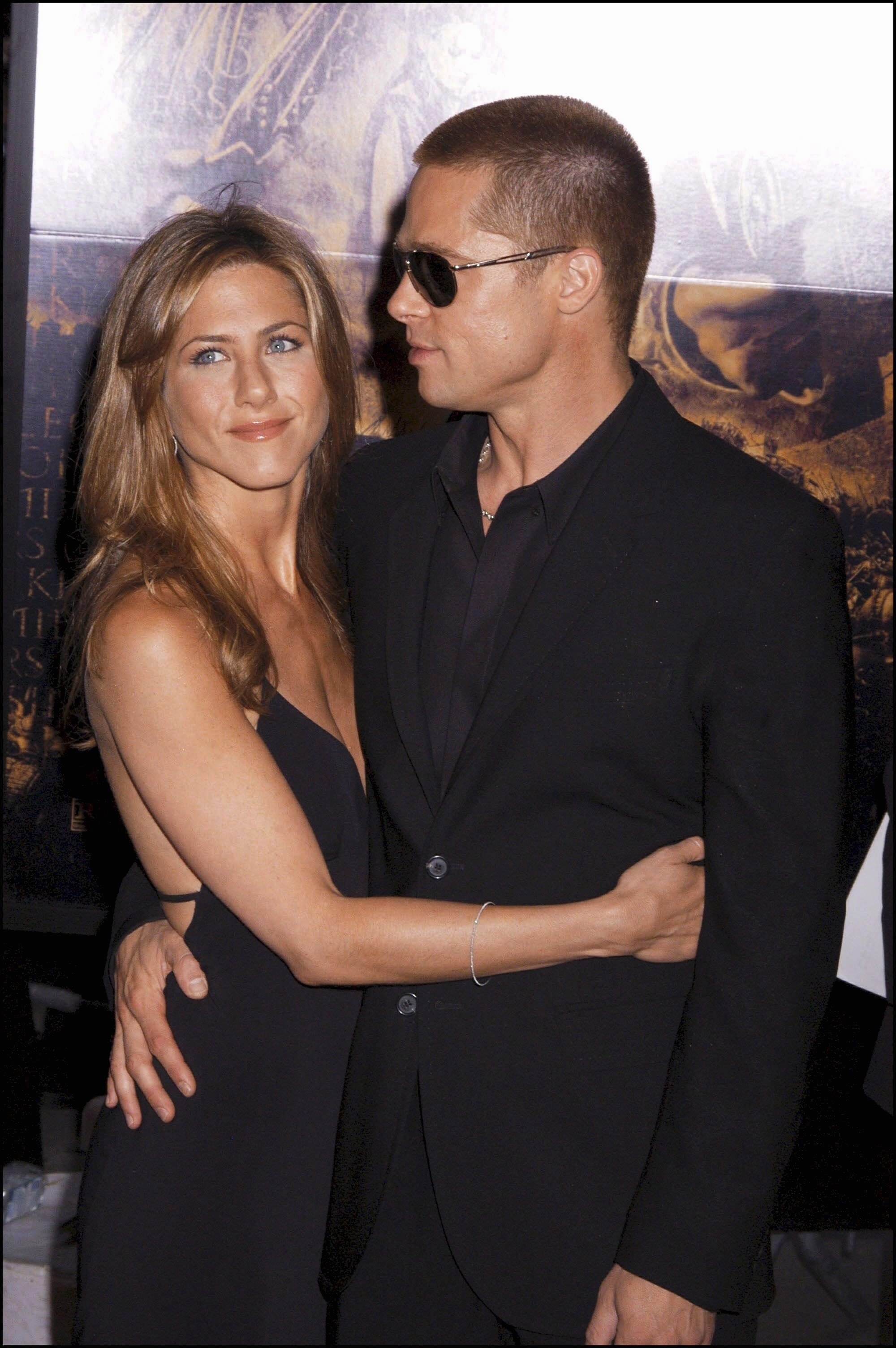

Aniston’s not wrong: Like other massively popular female stars, she functions as a lens through which others viewed, judged, and otherwise found the women in their lives (including themselves) wanting. Does your hair always look as good as Jen’s? Is your body always as svelte? Do you look that effortless, that unchangeable and unaging, at every movie premiere? Gossip about Aniston’s breakup with Brad Pitt — and more than a decade of speculation afterward, concerning her relationship status, her pregnancy status, her heartbreak status — was a simultaneous act of concern (“I just want her to be happy!”) and schadenfreude. Sure, she’s perfect, this gossip quietly whispers. But her life isn’t!

This phenomenon is far from new. It’s the predominant, contradictory way society has processed famous women for well over a century: venerate, yet denigrate. Empower, then endlessly interrogate and question that power. And it’s simply not the same for men. No matter how many waves of feminist thought pass over us, we’re still out here on baby bump watch, cellulite watch, plastic surgery watch, desperately seeking out the lack in the women who otherwise seemingly have it all.

I’m sure Aniston was fed up with the endless “Brad and Jen, back together and pregnant with twins!” magazine covers long before 2016. But as she writes later in the piece, “I used to tell myself that tabloids were like comic books, not to be taken seriously, just a soap opera for people to follow when they need a distraction.” Indeed, that’s how I used to teach the idea of celebrity gossip to my undergrad students: It’s a melodrama, almost entirely alienated from the actual people it employs as characters, meant to make people feel distracted and like the world is composed of good people and bad, heroes and villains, Jens and Angelinas.

Usually that fed-up-ness comes later in life and a career, when a woman has had enough time to see exactly how both Hollywood, and society at large, sucks up desirable women, briefly exalts them, then spits them out once they become too demanding, too old, too obvious in their attempts to counter the effects of age. Sometimes, after a string of flops and increasingly bad roles, they disappear from sight. That’s what Renée Zellweger did, removing herself from Hollywood for seven years. Other times, their anger, filtered through the lens of a man, manifests onscreen as grotesque. (See especially: every role of Joan Crawford’s after, oh, 1950.)

Other celebrities tamp down the rage, use its energy to endlessly discipline the body into its previous form. The best example of this phenomena is Madonna, but there are countless others whose effort is slightly less visible, and thus more acceptable. Sometimes, that rage is transmuted into humor: most famously in “Last Fuckable Day,” the 2015 Inside Amy Schumer sketch in which Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Patricia Arquette, and Tina Fey celebrate the day “in every actress’s life when the media decides that you’re not believably fuckable.” It’s also in the lyrics to country supergroup the Highwomen’s “Redesigning Women,” which describes the unending labor of womanhood as “working hard to look good ’til we die.”

And some reemerge in righteous anger. I’ve always been struck by the fact that the women who first went on the record about Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse and harassment — Ashley Judd, Mira Sorvino, Rose McGowan, and Rosanna Arquette — had reached the age, and place in their careers, where they were no longer as desirable within the industry. McGowan had been trying to talk about Weinstein for years. But it took the other, confirming voices, to force others to take her and their anger seriously. I think of Uma Thurman, asked about Weinstein on the red carpet for her Broadway play, and the simmering rage as she responds that she was waiting to feel less angry before speaking about it. (The piece in which she did speak about it was titled “This Is Why Uma Thurman Is Angry.”)

And these are just the pop culture manifestations. The 2016 election of Donald Trump — who, at that point, had been accused of multiple counts of sexual assault and misconduct — sparked a wave of outrage and frustration that coalesced into a wave of writing (“The Importance of Being an Angry Woman,” Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her, Rebecca Traister’s Good and Mad, Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage) and the 2017 Women’s March, which drew between 3 million and 5 million people. An unprecedented number of women went on to not only run for office in 2018, but volunteer en masse for campaigns — and a huge number, if not the majority, of those volunteers were between the ages of 40 and 80.

One of the primary motivators? Unmitigated anger. A 2018 Elle survey found that 74% of women consumed news at least once a day that made them angry — and 78% of Democratic women reported feeling more angry than the year before. The Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court confirmation hearings only exacerbated the feeling: “This anger will not subside,” Suzanne Moore wrote in the Guardian, “it will keep flowing.”

Various pop culture artifacts have attempted to channel that anger — and that curious sense of liberation — since the election. Top of the Lake and How to Get Away With Murder were ahead of the curve. Hustlers is ostensibly about class rage, but it’s also about women using that anger in a form of class revenge specifically against men. Atomic Blonde and Red Sparrow are essentially women’s revenge fantasies. The Good Fight is resistance porn with women as its rightful heroines. Big Little Lies. The beatification of Ruth Bader Ginsberg. Jane Fonda protest appreciation. Dead to Me. The entire trajectory of Kesha’s career. Ax-throwing centers. Jessica Jones. Etsy cross-stitches emblazoned with f-bombs and “Nevertheless, she persisted.” The resurgence of Riot Grrrl. The Handmaid’s Tale. Dietland. Unbelievable. A million different true crime podcasts, seemingly all of them hosted by women.

Some of these narratives provide catharsis (pushing a rapist down a set of stairs) while others, especially those connected to real life, are ongoing struggles without closure. The Morning Show is undoubtedly part of this trend, to the point that its underlying premise was rejiggered after Matt Lauer was ousted from the Today show following allegations of sexual assault. At one point in the first episode, a clip of Witherspoon’s character shrieking “I’m exhausted!” goes viral, setting up the premise for one of two main storylines for the show. The other: how Aniston’s character, a Katie Couric–like morning show host, will deal with her fury over the fact that her cohost, Mitch Kessler (Steve Carrell), was fired for serial sexual misconduct, while also fending off attempts to exchange her with someone younger and perkier.

Gossip about Aniston was a simultaneous act of concern (“I just want her to be happy!”) and schadenfreude. Sure, she’s perfect, this gossip quietly whispers. But her life isn’t!

But a surfeit of anger doesn’t necessarily make for a compelling narrative, and The Morning Show has been largely panned by critics, many of whom have honed in on the show’s lack of cohesive identity. For the New York Times’ James Poniewozik, it felt “like something assembled in a cleanroom out of good-show parts from incompatible suppliers.” The Ringer’s Alison Herman declared the show “has everything but feels like nothing.” But the thrill to me, and what will keep me watching, is the way the show, and the discourse around it, functions as a commentary on the constrictions of female stardom.

Later in the first episode of the show, Alex shows up at her former cohost’s house, soaked by the rain. She has to sneak into his house to talk to him so that the press wouldn’t see her and interpret it as giving sympathy. “I live a really strange existence,” she says to him, at once furious and exhausted. Not long before, she’d faced a half a dozen people in her living room, trying to choreograph the specifics of her public-facing reaction. In a few hours, she’d have to be back in bed, only to repeat it all over again with another 3:30 a.m. alarm the next day, and the day after that, and the day after that.

A lot of people wake up early to go to jobs that take a lot out of them. But this is a specific commentary on the labor of celebrity, which is often ignored and erased or written off as “fun” or “glamorous.” The task of always being camera-ready, always prepared to have your actions and fashion choices and body and walking style scrutinized, always ready to react with graciousness to anyone who approaches you — that would be exhausting for any celebrity, but it’s particularly exhausting for women, for whom the acceptable range of looks and behaviors is vanishingly small.

David Letterman can grow a Santa Claus beard and it’s funny. Justin Bieber can dress like Justin Bieber and it’s fine. But a female celebrity leaving the house unkempt is an invitation to show up in the pages of Us Weekly. Aniston is known for wearing variations on the same theme: jeans and black tops, black workout gear, or, on the red carpet, slim-fitting black dresses. Her hair is almost always down, always the same honeyed light brown, and almost always styled in the same way (grown-out versions of “The Rachel”).

Aniston’s never been pregnant, as far as we know, and despite the number of breathless “bump alerts,” her body has never significantly changed in size. She’s stayed toned and lithe, her face fresh and dewy, her style steady but irreproachable. And still she’s criticized. Her Morning Show character offers a means to display and embody that contradiction in a way that’s difficult to express, in real life, in a way that doesn’t come off as ungrateful or bitchy. (In the past, the closest Aniston has gotten to an abrasive statement came in 2006, when she told Vanity Fair that Brad Pitt had “a sensitivity chip missing.”)

But as Morning Show showrunner Kerry Ehrin explains, “Jennifer is a grown woman. She’s got a lot of depth, and she’s lived a life, and it was exciting to be able to reach into those real human depths,” including the ability to “shrug off the burden of likability.” Director Mimi Leder told the Hollywood Reporter that she purposefully let shots linger on Aniston into the moments when her composure begins, ever so slightly, to crumble. “That’s part of the visual language of the show,” she said. “I wanted to hold shots longer than normal — like Jen staring in the mirror during the first episode. Normally you’d cut sooner, and they asked me to, but I found her fascinating.”

Aniston is fascinating. But the vast number of roles offered to her — and that she’s taken, for whatever reason — work hard to suggest otherwise. The role of Rachel Green set her image in concrete, but even the slightest detours from that image (The Good Girl, Friends With Money, Cake, Dumplin’) have shown just how interesting an actor she is. But those performances have been largely ignored, either because they went straight to Netflix (Dumplin’) or because they didn’t offer the Aniston image, that experience of charisma and likability, that so many have come to expect with one of her performances. What The Morning Show does is offer both: the star and her exhaustion, the charisma and its livid dark side, the glamour and the sacrifice.

When Aniston joined Instagram last month — a move, she admits, made specifically to promote the show — she literally broke the platform. She now holds the record for the fastest person to amass 1 million followers: It took her just 5 hours, 16 minutes. Today, more than 18.5 million people follow her account, which features posts that are thus far a mix of #TBTs, shots that show just how much work goes into the glamorization process. When she joined Instagram, a friend told me: “I’m not even much of a fan, but when I saw her, the gravitational pull was too strong.”

That’s the sort of star Aniston is: rare and irresistible. Right now, she’s straddling the age where women have previously become unfuckable, uncastable, or invisible — at least until they can reappear, a decade or two later, in Hot Helen Mirren mode. What will this new shade of Aniston evolve into? She’s signed on for another season of The Morning Show. She’s set to play the president — with Tig Notaro as her wife — in an upcoming film for Netflix. In Good and Mad, Rebecca Traister writes that “women’s anger spurs creativity and drives innovation in politics and social change, and it always has.” Anger can be exploited for entertainment, as it often is by men. But in the hands of women — Aniston, Witherspoon, and the women who serve as the show’s showrunner and director — it becomes something far more expansive and compelling.

The main complaint with The Morning Show is that it can’t decide what kind of show it is. Its first, pre-#MeToo iteration, based almost exclusively on the politics of morning show hosting, or its second, woman-led, post–Matt Lauer version, grappling with much larger questions of culpability and solidarity. That’s how I’ve long felt about Aniston. Is she the prickly, acerbic, neurotic weirdo, or the girl next door in the sheath black dress and the bland rom-com? Seeing her bifurcation as Alex felt like a revelation: Here’s who society, and celebrity, forces me to be, and here’s how the rest of me absorbs and reacts to that mandate. Famous women really are just like us: mad as hell, and increasingly unwilling to hide it. ●