December

14

December

14

Star Wars Science: Sci-Fi Syndrome, Neuroprosthetics, and Luke Skywalker’s Hand

Luke’s back, baby! Image: GamerHeadquarters.com

It’s that time of year, friends. Holiday lights are going up, snow is starting to fall, and a new Star Wars movie is about to come out! We’re all amped up to see the next chapter in Rey’s journey, this time with an experienced mentor by her side. In the new film The Last Jedi, we’ll see Luke Skywalker again at last – older, more rugged, and with a less polished-looking prosthetic hand than before. Luke lost his hand to his father’s lightsaber at the end of The Empire Strikes Back. Just a few scenes later, thanks to the advanced technology of the Star Wars universe, it was like he’d never lost it at all. A few zaps, a droid beep, and a panel snapping shut – voila! Good as new.

Over at Neuro Transmissions, we’ve made a video all about the variety of prosthetic hands available here on Earth – and highlighted some incredible advances being made in creating devices that not only look and move like real hands, but can even feel like them.

It’s easy to see why developing high-tech prosthetics would be useful – after all, Luke’s hand looks and operates just like the original. But are advanced neuroprosthetics the best option for every person who’s missing a limb?

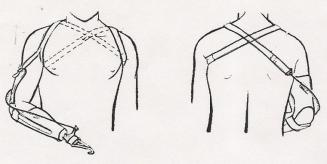

An example of a below-elbow body-powered arm, using a harness and cables to open and close the hand. Image from Upper Limb Prosthetics

When it comes to prosthetic hands, users generally have two basic options. Cosmetic hands look natural but are essentially non-functional. Body-powered hands may not lookas natural but offer some functionality, like opening and closing, using control cables strapped around the shoulders and torso. These non-robotic devices allow users to grasp objects by twisting their bodies, and can even provide some tension feedback information, making them easier for wearers to use [1]. They’re not fancy, but they can get the job done.

An example of a myoelectric prosthetic arm, worn by a US Marine. Image: the US Navy on WikimediaCommons

More advanced prosthetic options include myoelectric devices, which use non-invasive electrodes on the skin to detect the electrical signals produced by the remaining muscles in the arm to generate movement in a few different dimensions – like opening and closing the hand and rotating the wrist [2]. Researchers are currently working on more advanced neuroprosthetic approaches – devices that use electrodes to integrate directly with the nervous system to provide more freedom and control of motion [3]. Someday, these devices could mean that patients end up with hands like Luke’s – arms they won’t even have to think about moving, and hands that are just as dextrous and agile as a natural human hand.

But even though researchers have made incredible breakthroughs on creating devices that can move and feel almost natural, there’s still a lot holding us back. We haven’t figured out how to build electrodes that will last for a lifetime – most of them clog up within a year or so. The robotic prosthetics are complicated, expensive (on the order of hundreds of thousands of dollars), and can be fragile. And the most advanced devices are still in early experimental phases, nowhere near ready for the market. Scientists are still mapping out all the nerves that send and receive signals from the hand and figuring out how to create electrodes and computers small and powerful enough to emulate all the functionality of the missing neural machinery.

A ‘bionic’ hand design – fun and functional, but do designs like these set unrealistic expectations? Image: StarWarsRey on WikimediaCommons

So what does that mean for the users of these devices? Well, it can mean that there’s a divide between the devices we see in the media – like Luke’s good-as-new-hand – and what’s actually available on the market. And according to The War Amps Advocacy Program, it can even lead the public to believe that prosthetics are so advanced that they actually offer superhuman abilities to their users. They have dubbed this perception “sci-fi syndrome”, arguing that it prevents the government and private insurers from providing adequate prosthetics to amputees who need them [4].

But even beyond the financial concerns faced by users who need prosthetics, amputees themselves can sometimes fall prey to the unrealistic expectations set by the media. “I’ve been in clinic a few times, and I’ve seen multiple instances of amputees coming in to get fitted for a prosthesis and have grand notions of all the amazing things prosthetic limbs can do,” says Eric Earley, a graduate student of biomedical engineering at Northwestern University whose work is focused on motor learning and robotic prosthesis control. “Even though body-powered devices can sometimes be the best choice for an amputee, many will reject them because they perceive body-powered devices to be useless and the super-advanced devices to be unparalleled. In actuality, some people do better with body-powered devices (or, indeed, no device at all) than with the expensive devices.”’

Not all patients make good candidates for advanced devices due to other underlying health concerns, and for folks in some professions – like farming, or construction – wearing an expensive, delicate prosthetic that can’t get wet or dirty just doesn’t make sense. Currently, the market is set up to reward prosthetists – professional prosthetic designers and creators – who sell the most advanced, and thus most expensive, devices. And patients who have high expectations for what a prosthetic limb should look and feel like may not be aware of all of the options available to them.

This isn’t to say that the scientists working to develop advanced robotic neuroprosthetic limbs are in the wrong. We’re not at Luke-Skywalker-level hands yet, but then, we don’t have lightsabers yet either. Until we do, it’s important that doctors and prosthetists work with patients on a case-by-case basis, learning about their personalities and their lifestyles in order to provide them with the most appropriate limbs for their needs. As science writer Rose Eveleth puts it, “The measure of success for a patient isn’t how state-of-the-art their legs or arms are, but how well they can live their lives.” [5]

Alie Caldwell is a fifth-year graduate student of Neurosciences at UCSD, where she studies the roles of astrocytes in neuronal growth and development. She is also the co-creator of Neuro Transmissions, a YouTube channel all about the brain.

Sources:

- Smit, G. et. al. “Efficiency of voluntary opening hand and hook prosthetic devices: 24 years of development?” J Rehabil Res Dev. 2012;49(4):523-34.

- Purushothaman, G. “Myoelectric control of prosthetic hands: state-of-the-art review” Med Devices (Auckl). 2016; 9: 247–255.

- Warwick, K. et. al. “The Application of Implant Technology for Cybernetic Systems” Arch Neurol. 2003;60(10):1369-1373.

- Forbes, B. N. & Petlock, A. “‘Sci-fi syndrome’ hurts struggle for artificial limbs”. Opinion. The Star [Toronto] October 2, 2017

- Eveleth, R. “When State-of-the-Art is Second Best”. PBS NOVA Next [Boston] March 5, 2014

You must be logged in to post a comment.