Memes aren’t built to last. This is an accepted fact of online life. Some of our most beloved cultural objects are not only ephemeral but transmitted around the world at high speed before the close of business. Memes sprout from the ether (or so it seems). They charm and amuse us. They sicken and annoy us. They bore us. They linger for a while on Facebook and then they die—or rather retreat back into the cybernetic ooze unless called upon again.

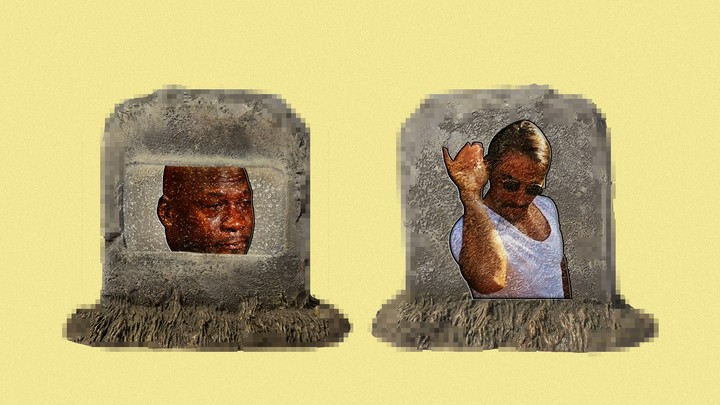

The constancy of this narrative may be observed in any number of internet memes in recent memory, from the incredibly short-lived (Damn Daniel, Dat Boi, Salt Bae, queer Babadook) to the ones seemingly too perfect to ever perish like Harambe the gorilla and Crying Jordan. The recent “Disloyal Man Walking With His Girlfriend and Looking Amazed at Another Seductive Girl,” the title of the stock image shot by photographer Antonio Guillem, just made the rounds a few months ago.

At a glance—even from a digital native—meme death seems like a much less mysterious phenomenon than meme birth. While tracing the origin of any individual meme requires a separate trip down the rabbit hole, it makes sense to assume that memes die because people get tired of them. Even as a concept such as “average attention span” is not incredibly useful to psychologists who study attention (different tasks require different attention strategies), there’s a general assumption that this number is shrinking. “Everybody knows” a generation raised on feeds and apps must have focus issues, and that assessment isn’t totally false. Our devices are “engineered to chip away at [our] concentration” in what’s called the “attention economy,” writes Bianca Bosker in The Atlantic, and apps such as Twitter keep us anxious for the next big thing in news, pop culture, or memes. Our overextended attention leads to an obvious explanation for meme death: We are so overstimulated that what brings us joy cannot even hold our focus for long. But is that really why memes die?

In 2012, the third and final meeting of ROFLCon, a biennial convention on internet memes hosted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, anticipated a shift in the formal qualities of meme culture, ushered in by social-media sites like Facebook and Twitter. Indeed, this was the tail end of an era, one defined by the once-ubiquitous image-macro template as applied to subgenres like Advice Animals, LOLcats, and Doge. At the conference, 4chan founder Christopher “moot” Poole was “wistfully nostalgic for the slower-speed good ol’ days,” Wired’s Brian Barrett reported, fearful that memes gone “mainstream” would betray the niche communities that considered memes a kind of intellectual property all their own.

“These days, memes spread faster and wider than ever, with social networks acting as the fuel for mass distribution,” Wired’s Andy Baio wrote that same year. “As internet usage shifts from desktops and laptops to mobile devices and tablets, the ability to mutate memes in a meaningful way becomes harder.” Both Poole and Baio suggest that memes lose something essential—whether a close-knit humor or the opportunity to add a unique, creative contribution—when they are enjoyed by a larger community. Social networks, some feared, would drive memes to extinction. But Chris Torres, the creator of Nyan cat, anticipated that the break from the old-school would be a good thing. “The internet doesn’t really need to have its hand held anymore with websites that choose memes for them,” he told The Daily Dot’s Fernando Alfonso III in 2014. “As long as there is creativity in this world then they are never going away. This may just be the calm before the storm of amazing new material.”

And in 2017, it’s clear that the doomsday crew vastly underestimated internet users’ creativity. Increased mobility and access across platforms and communities has brought to the surface some of the funniest and weirdest content the web has ever known. Contrary to what Poole and Baio implied, weird humor and memes are hardly the exclusive domain of Redditors or the mostly white tech bros who populated ROFLCon. Today, many of the internet’s favorite memes come from fringe or ostracized communities—often from black communities, for whom oddball humor has long been an art form.

* * *

While internet memes categorically remain alive and well, individual memes do seem to die off faster than in Poole’s “good ol’ days.” They just don’t last like they used to: Compare the lifespans of say, Bad Luck Brian to Arthur’s clenched fist or confused Mr. Krabs. But if overexposure is partially to blame for their demise, it certainly doesn’t tell the whole story. Nor can it alone account for the varied lifespans amongst concurrent memes. Crying Jordan lasted years; did Damn Daniel even last two weeks? Salt Bae took over social media in January 2017, but was quickly overshadowed by gifs of Drew Scanlon (“white guy blinking”) and rapper Conceited (“black guy duck face”), which lasted throughout the spring.

Why do some memes last longer than others? Are they just funnier? Better? And if so, what makes a meme better? The answer lies not in traditional memetics, but in the study of jokes.

Though he has yet to return to the subject in earnest since 1976’s The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins remains a specter over discussions of internet memes. The study, in which Dawkins extends evolutionary theory to cultural development, has been elaborated upon as well as critiqued in the three decades since its publication, spawning the field of memetics and drawing ire from neurologists and anthropologists alike. In The Selfish Gene and in memetics at large, “memes” are components of culture that survive, propagate, and/or die off just like genes do. Memetics in general is uninterested in why these components survive, or the contexts that allow them to do so—and much as individual persons are considered unwitting actors within the gene pool at large, so too are our intentions deemed irrelevant when it comes to the transmission of culture.

On the scientific side, researchers such as the behavioral scientists Carsta Simon and William M. Baum worry that the scientific rigor implied by “memes as genes” has yet to be met by actual memetics research. Anthropologists and sociologists “charge that memetics sees ‘culture’ as a series of discrete individual units, and that it blurs the lines between metaphor and biology,” wrote the Fordham University researcher Alice Marwick in 2013. And, as I’ve written, thinking of memes solely in this way tends to “relegate agency to the memes themselves” as if they are not subject to human innovation, creation, and responses. Memetics, more interested in the movement of memes than their content, may be helpful in tracking or predicting meme lifespans, but cannot fully account for how human participation factors in.

The weakness of the memes-as-genes theory becomes more apparent in an online context. By Dawkins’s deliberately capacious definition, the word “meme” may apply to sayings, bass lines, accents, clothing, myths, and body modification. In this vein, a meme in terms of digital culture could mean a viral hashtag like #tbt, tweet threading as a form of storytelling, or netspeak. However, memes as they’re popularly discussed nowadays often index something much more specific—a phrase or set of text, often coupled with an image, that follows a certain format within which user adjustments can be made before being redistributed to amuse others. Also known as: a joke.

Jokes are more than funny business and, in fact, laughter (even in acronym form) is not the standard for defining what is or is not a joke. We often laugh at things that are not jokes (like wipeouts); and jokes do not always elicit laughter (like a bad wedding toast). That memes employ humorous devices does not de facto render them jokes. But as it so happens, memes and jokes do share several formal qualities. And looking at memes as jokes may also help answer why some memes dry up, and why and when others return.

“Only when it comes to jokes is the idea of ‘meaning’ so often vehemently denied,” Elise Kramer, an anthropologist currently at the University of Illinois, wrote in a 2011 study of online rape jokes. “Poems, paintings, photographs, songs, and so on are all seen as having meaning ‘beneath’ the aesthetic surface, and the relationship between the message and the medium is often the focus of appreciation.” Kramer’s point is not that jokes cannot be explicated or unpacked, but rather that jokes—and memes, I’ll add—uniquely and deliberately make depth inconsequential to their appreciation. As displayed by recent gaffes like Bill Maher’s “house nigger” joke and Tina Fey’s “let them eat cake” sketch, comedy remains the most resilient place for ethically dodgy art. Reading “too much” into jokes is frowned upon and offended audiences are often told “it’s not that deep.”

Memes are viewed the same way, even by those who write about them. There’s an obligatory defense embedded in most meme coverage, as if writers sense they must keep the analysis at a minimum lest they spoil the fun. In a love letter to Doge, Adrian Chen wondered if “by writing it I played a crucial role” in guiding the meme toward obsolescence, “proving once again that writing about internet culture is basically inseparable from ruining internet culture.” Last summer, while declaring Harambe too dark to be corporatized and therefore too weird to die, New York magazine’s Brian Feldman admitted “there are other ways to end the Harambe meme. Like writing a think piece about it.” A month later The Guardian’s Elena Cresci repeated the line like gospel: “When it comes to memes, there’s a rule: It is dead as soon as the think pieces come out.” She even likens memes to jokes directly, asserting that “when memes go mainstream it means they’re not funny anymore. Memes are just in-jokes between people on the internet, and everyone knows jokes are much less funny one you’ve explained them.”

This evaluation shows another way memes and jokes are similar: Both are, returning to Kramer, “aesthetic forms where felicity (i.e., ‘getting’ it) is seen as an instantaneous process.” Unlike a painting, novel, or even a rousing Twitter thread which one is expected to “savor” like “a good meal,” the person who does not get the joke or meme immediately is considered a lost cause. “The person who spends too much time mulling over a joke is accused of ruining it,” Kramer writes. Tech reporters included, apparently.

But a commonly held accusation doesn’t equal truth. We might observe a correlation between a summer of Harambe think pieces and its decline not long after, or blame The New Yorker for making Crying Jordan uncool, but it’s worth noting that such pieces exist because their subject matter has reached a certain critical mass that makes them worth writing about. (With all due respect, I don’t believe New York Magazine, The New Yorker, or even The Atlantic is propelling memes into zeitgeist.) “Mainstream” doesn’t exactly signal the death knell, either. The “white guy blinking” gif continues to make the rounds when called upon—following the season finale of Game of Thrones, for example—and the line “ain’t nobody got time for that,” from a popular 2012 meme, met hearty laughter and applause when I attended Disney’s Aladdin, the musical, this fall. Some memes “die” and come back again, some surge and then are all but obsolete. Applying theories on the joke might help explain why.

* * *

Because of the shared attributes between jokes and memes, research on jokes can provide a template for how to study memes as both creative and formulaic. That includes finally finding a satisfactory answer to how and why memes “die.” In a 2015 thesis, Ashley Dainas argues that what folklorists call the “joke cycle” is “the best analogue to internet memes.” The joke cycle describes the kinds of commonplace, well-circulated jokes that become known to mass culture at large, such as lightbulb jokes or dead-baby jokes. Unlike other jokes that are highly specific—an inside joke between two friends, for example—these jokes have a mass appeal that compels them to be shared and adjusted enough to stay fresh without losing the source frame. These jokes evolve in stages, from joke to anti-joke, and will retreat over time only to resurge again later, even a whole generation later.

Viewing jokes as cultural artifacts, researchers aren’t just concerned with plotting a joke’s life cycle but also the social contexts that make the public latch onto a specific joke during a certain time. Lightbulb jokes, for example, arose as a type of ethnic joke in the ’60s and “had swept the country” by the late ’70s, wrote the late folklorist Alan Dundes. The joke, with its theme of sexual impotence (something/one is inevitably getting screwed), was “a metaphor which lends itself easily to minority groups seeking power.” It was one means to thinly veil prejudices, using the joke as an outlet for anxieties about the civil-rights legislation achieved in the ’60s, and carried out in the ’70s and beyond. Hence most lightbulb jokes, even when they don’t cross ethnic or racial lines, tend to be a comment on some social, cultural, or economic position—“How many sorority girls does it take to change a lightbulb?” et al.

Dead-baby jokes became popular in around the same period, a time marked not only by racial upheaval but gendered, domestic changes alongside second-wave feminism: increased access to contraception, sex education in school, women forestalling or even forfeiting motherhood in favor of financial independence. While determining exact causal relationships is a sticky matter, Dundes advised, “folklore is always a reflection of the age in which it flourishes ... whether we like it or not.”

And so too memes. Like jokes, memes are often asserted to be hollow, devoid of depth, but it would be foolish to believe that. Memes capture and maintain people’s attention in a given moment because something about that moment provides a context that makes that meme attractive. This might provide a more satisfying, but also more expansive, answer than simple boredom for why memes fall out of immediate favor. The context that makes a meme, once gone, breaks it. New contexts warrant new memes.

The 2016 U.S. election season and aftermath brought into focus how memes become political symbols, from Pepe the Frog to protest signs. In Pepe’s case, the otherwise chill and harmless character created by artist Matt Furie in the early 2000s was on the decline until he got a new context when the alt-right reappropriated him leading into the election. Pepe was resurrected from obscurity when internet culture found a new need for the cartoon’s special brand of male millennial grotesquerie.

Memes don’t just arise out of atmospheric necessity but disappear as well. The same election season effectively killed off Crying Jordan, when perhaps the idea of loss suddenly became too poignant, too meaningful for the disembodied head of a crying black figure to read as playful. Memes catch on when we need them most and retreat when they are no longer attuned to public sentiment.

Ultimately, fans and founders of the old-school meme-distribution methods aren’t entirely wrong. Flash-in-the-pan memes like Dat Boi are limited by a format that restricts the meme’s ability to evolve to the next creative iteration of itself. Dat Boi—which didn’t have much going on beneath the surface weirdness of a unicycling frog—could mutate no further, got stale, and trailed off without the chance to become cyclical (the irony) in a way that would allow it to last beyond its moment. Harambe, for all its weirdness, could not survive much beyond the life of the news story that spawned it. (In the meantime, as a friend points out, the Cincinnati Zoo has been working overtime with PR for nine-month-old hippo Fiona, who’s since become something of an internet sensation herself.)

The “expanding brain” meme, however, continues to chug along for the greater portion of 2017. The meme, which mocks the infinite levels of intellectual one-upmanship common to any and all online discussions, is exactly what’s called for in this post-truth moment where everyone is a pundit. I foresee this one sticking around for a long while yet. Meanwhile, it’s easy to see why a festive meme like “couples costume idea,” would come and go in accordance with the month of October.

As Dundes cautioned with jokes, we should not be too confident in claiming cause and effect between memes and their present contexts. Time and distance can assist us in evaluating why some memes ignited our feed, why some burned out quickly, and why others stuck around. The answers to these questions are not so random, but suggestive of the cultural, political, and economic times we live in. Provided we actually remember the memes.

“The World Wide Web has become the international barometer of current events,” the music librarian Carl Rahkonen wrote back in 2000. “The life of a joke cycle will never be the same as it was before the internet.” No kidding. The pace of life online tests the durability of culture like nothing else before, but it is still ultimately culture. The memes we forget say as much about us as the memes that hold our attention—for however long that is. We create and pass on the things that call to our current experiences and situations. Memes are us.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.