The Federal Communications Commission on Thursday (Dec. 14) successfully voted to repeal the Open Internet Order. Split along party lines, the vote hands FCC chairman Ajit Pai a major victory and potentially allows US telecoms to block, slow, or charge more for certain content.

An army of nonprofits, politicians, and activists, energized by the outpouring of grassroots opposition, is now working to reverse that move. They have two options, neither a slam dunk. But as US politics continues its wild ride into the unprecedented, undoing the FCC’s decision within the next year is possible.

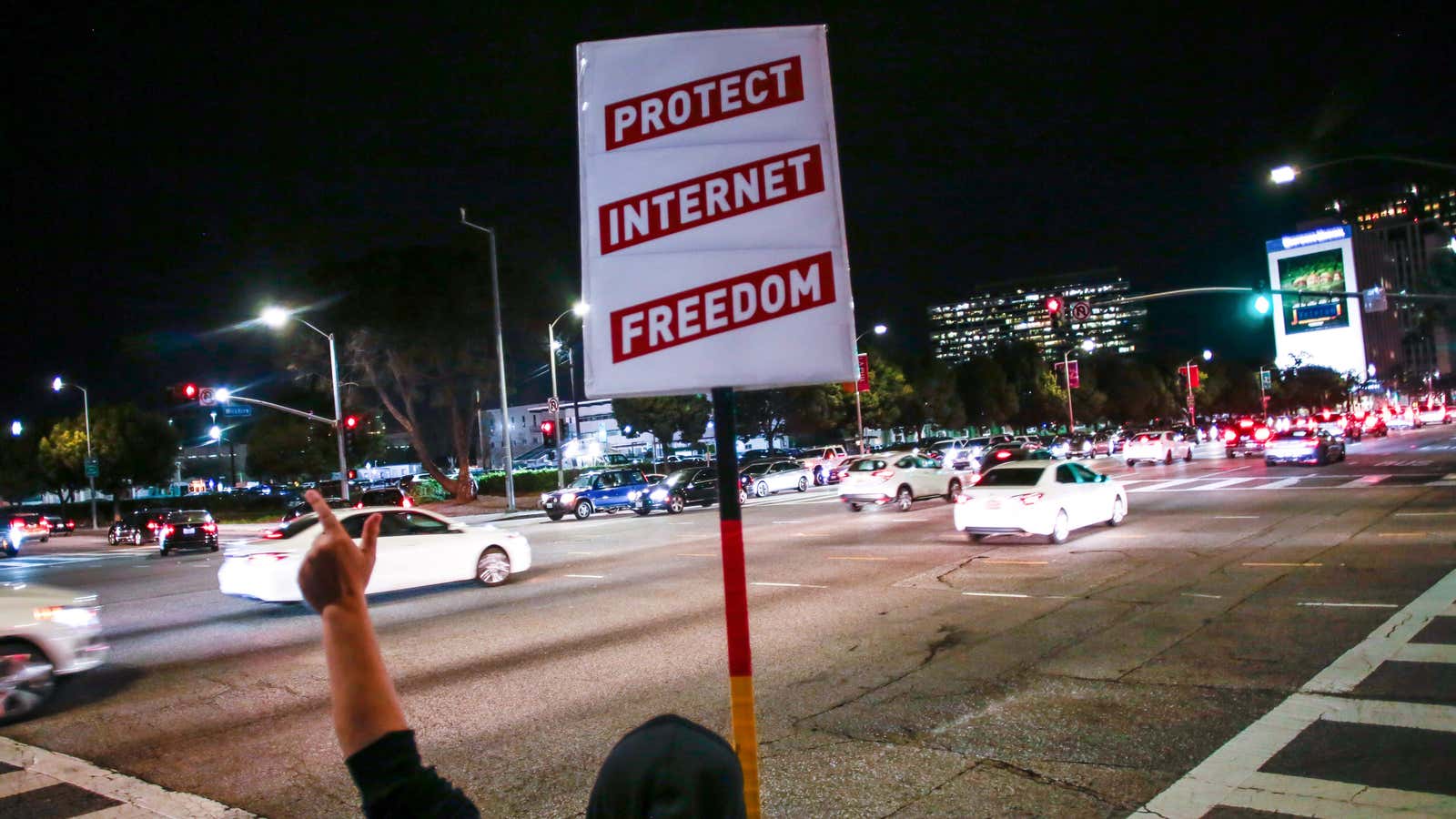

Net neutrality opponents storm Capital Hill

Option A is Congress. Legislators in the House and Senate could simply pass a law that takes net neutrality out of the FCC’s hands. That’s unlikely. With partisan gridlock in Washington, and the ambitious legislative calendar Republicans have laid out for themselves, passing new laws while the clock ticks toward contentious mid-terms is a tall ask.

Little-used until recently, a law known as the Congressional Review Act (CRA) does offer another path forward. Legislators of either party can petition to reverse agency rulings, after which Congress must pass a “resolution of disapproval” with a simple majority in the Senate (avoiding the 60-vote hurdle of a filibuster). This permanently reverses agency actions. Before 2016, only one reversal occurred under the CRA: Congress (with sign-off from George W. Bush) undid Clinton-era rules requiring companies to help prevent ergonomic injuries in the workplace.

In 2017, Republicans under Donald Trump effectively weaponized the CRA for partisan warfare, eliminating 15 (pdf) of Obama’s regulations. With net neutrality, the rule could be used to actually save one.

Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania representative Mike Doyle, both Democrats, have said they plan to bring a CRA petition to reverse the FCC ruling to the floor. If it passes, and receives the signature of the president, the FCC’s ruling would be reversed. The Obama-era Open Internet Order of 2015 would be reinstated as policy and the agency would be prohibited from issuing any similar rules without congressional authorization.

It’s unlikely, but not quite as crazy as it sounds. Despite the GOP’s near-total control of the federal government, Republicans have been peeling away from the party line on net neutrality for months now. Senator Susan Collins of Maine criticized Pai’s proposal in November, and representative Jeff Fortenberry of Nebraska tweeted his disapproval earlier this month. Maine Representative Angus King (independent) criticized Pai’s handling of net neutrality last week. “This is a matter of enormous importance with significant implications for our entire economy, and therefore merits the most thorough, deliberate, and thoughtful process that can be provided,” he wrote in a statement. “The process thus far in this important matter has not met that standard.”

Most recently, Colorado representative Mike Coffman lobbied Pai to delay hearings, receiving no response.

It’s conceivable, if improbable, that a deeply unpopular net neutrality rule passed under a fairly unpopular president and Congress will be tossed overboard. ‘Tis the season for unusual politics.

Courts will be casting a skeptical eye on the FCC

The FCC decision, opponents say, is riddled with procedural and substantive errors that will sink its enactment in federal courts. As it stands, the repeal goes into effect unless courts issue a stay (unlikely), but a federal judge will make a final determination as to whether the FCC’s process, and its conclusions, are legal.

Neither is a sure thing.

This week, state attorney generals demanded that Pai delay the net-neutrality vote while they investigated as many as two million fake public comment made on the FCC website, which received at least 21 million submissions. Many of those comments appear to have been made by bots. ”A careful review of the publicly available information revealed a pattern of fake submissions using the names of real people,” states a letter from 18 attorney generals (pdf). “This is akin to identity theft on a massive scale and theft of someone’s voice in a democracy is particularly concerning.” A separate letter was sent by New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman. He is pursuing his own investigation questioning the FCC’s commitment to consider legitimate public comment in its decision.

Shortly after the FCC vote on Dec. 14, Schneiderman filed a suit to stop the change.

“There will be multiple lawsuits in multiple locations,” says Phillip Berenbroick, senior policy counsel with the nonprofit Public Knowledge which will be suing the FCC, along with Free Press and many others. “The FCC has a duty to run a process that has integrity and they’ve failed to do it. That’s going to be challenged in courts.”

Whatever the outcome, it will not be quick. When the FCC passed the Open Internet Rule in 2015, it took about 15 months for the challenges to work their way through the court system (the agency eventually prevailed over lawsuits from telecoms). This time, Pai’s policy process could be found wanting. “The FCC order [pdf] is 200 pages,” says Berenbroick. “It’s long on hyperbole, and short on legal and economic analysis.”