SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Lanao del Sur, Philippines – The classroom full of grade school learners chanted the three-word mantra, dutifully acting out corresponding hand gestures.

“Huwag lapitan! Huwag hawakan! Tawagin si titser!” (Don’t go near! Don’t touch! Call teacher!)

After the end of clashes between government forces and armed groups, Marawi residents are slowly heading back home. But first, they are learning how to recognize an unexploded ordnance or an improvised explosive device that may have been left over from the fighting.

For children, that starts with memorizing the three-rule mantra.

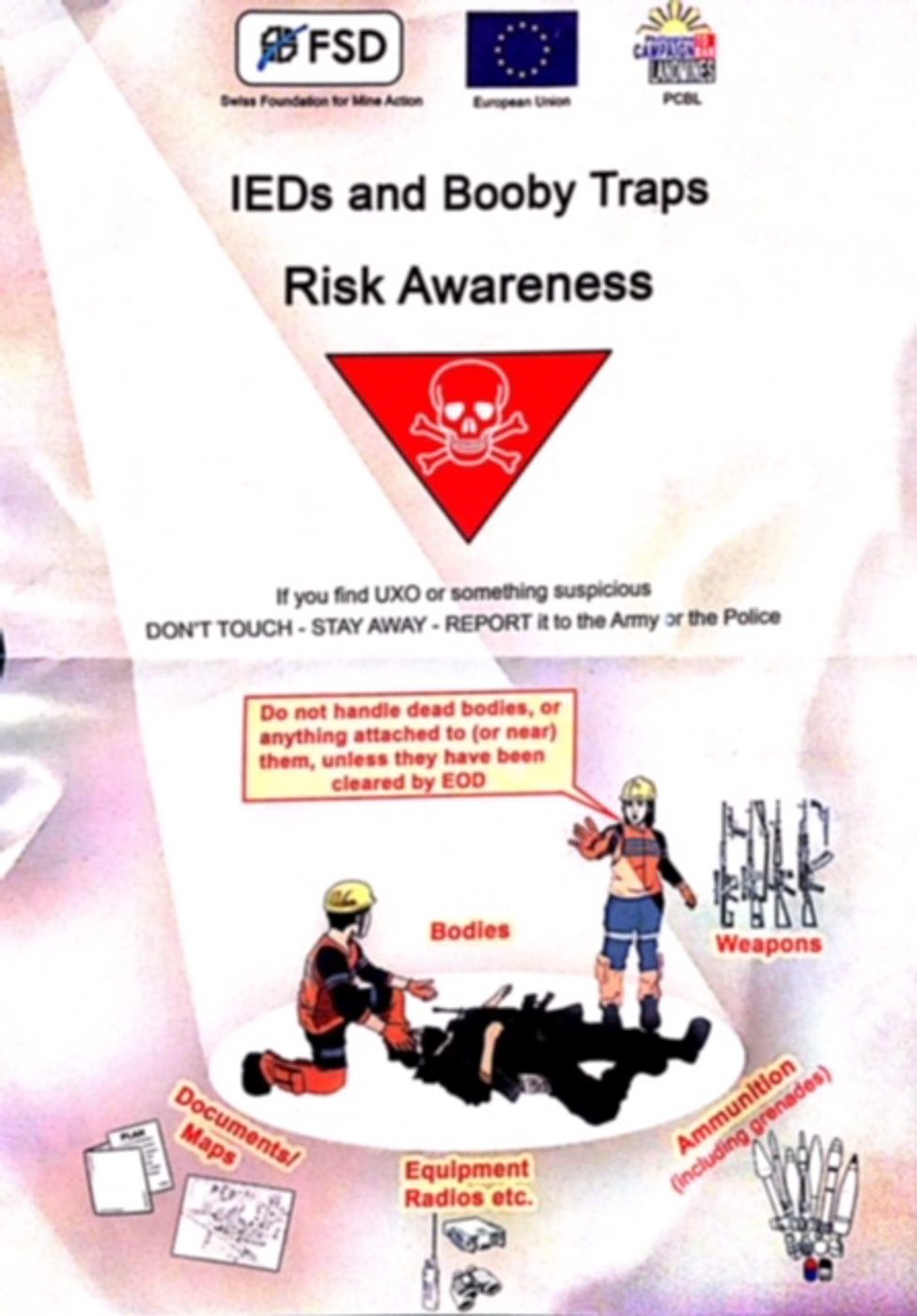

“Residents need to be aware of the risks posed by unexploded ordnance or bombs that were dropped but did not explode and improvised explosive devices,” said Namra Bagundang, a Mine Risk Education officer from Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD).

“Some mistake an unexploded ordnance for gold or something valuable because it is made of shiny metal. They may try to crack it open. Kids may think it is a toy and play with it. This is very dangerous and can cause the device to explode,” she added.

FSD Mindanao and its network of trained volunteers from the Department of Education (DepEd) conduct school visits to educate Marawi residents about the risks of unexploded ordnance and how to keep themselves and their families safe. The learning sessions are conducted in coordination with the Philippine military.

Displaced

More than 350,000 people were displaced from Marawi after the ISIS-inspired Maute Group overran the city on May 23. It took state forces 5 months to regain control of the city and drive out the local terrorists.

The months of intensive fighting with nearly daily airstrikes left Marawi City littered with unexploded ordnance. Improvised explosive devices reported to have been used extensively by Maute fighters may have been left behind, camouflaged by or hidden under debris.

Aerial bombs dropped during air strikes may not have exploded. Other natural occurrences like heavy rains may have transported an exploded ordnance to riverbeds and closer to residential settlements. This situation poses potential dangers to civilians returning to their homes.

The military had already conducted extensive clearing operations and employed bomb-sniffing canines to ensure that affected areas are safe for both residents and aid workers involved in rebuilding efforts.

Colonel Romeo Brawner Jr, deputy commander of Task Force Ranao, confirmed that 27 barangays have been cleared by the military. However, about 36 barangays in Marawi City remain closed for returning residents as the military continues its clearing operations.

The main battle area composed of 36 barangays is still closed to the public as the military continues its clearing operations there.

“The military and its partners will continue to work on making sure that residents who can return to their homes will be safe,” Brawner said.

Adult training

The basic three-rule mantra was taught to children with instructions such as how not to use a mobile phone near an explosive device because the electrostatic waves from the phone could detonate it.

While the grade school learners were being educated about the dangers of bombs, outside the classrooms, parents and other adult residents attended trainings on recognizing unexploded ordnances.

FSD started conducting these trainings in 2013, around the time of the Zamboanga siege. There were no injuries reported from unexploded ordnance or improvised explosive devices after the siege. Authorities said they would like to keep such safety record, noting the importance of conducting safety trainings.

At the Bobo Elementary School in Piagapo, an old bomb has been used as a school bell for years. The principal did not know where it came from or when the school has started using it.

“They think it may have been left by the Japanese,” FSD’s Bagundang said, referring to the period when the Japanese occupied the Philippines during World War II.

To end the training, FSD changed the old bomb with an actual school bell.

“We need to keep our message consistent so kids will not be confused,” Bagundang said, stressing that “bombs should not be touched nor should they be clanged like bells.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.