by Marc Hogan

July 16, 2015

Out of the more than 10,000 playlists on the new Apple Music is one called “Artists John Peel Helped Make Famous”. A longtime BBC Radio 1 DJ who died in 2004, Peel embodied the ideal of a music curator long before that phrase was buzzworthy. From Pink Floyd to PJ Harvey, he offered airtime to bands that he believed in. With his eclectic combination of knowledge, passion, and curiosity, Peel provided a model for what playlists could be.

Ordered lists of songs are as old as radio itself, but the idea of the playlist has gained particular currency in the past few years. As on-demand streaming services such as Spotify, Rdio, Rhapsody, Deezer, Google Play Music, YouTube Music Key, SoundCloud, Amazon Prime Music, Tidal, and now Apple Music have proliferated, each with vast and roughly similar music libraries, they’re now working to differentiate themselves by how well they help listeners sift through all that choice.

As simple as the concept might appear, approaches to today’s playlists are varied in a way that’s reminiscent of music itself. Computer algorithms or human curators? Editorial professionals or amateur compilers? Lesser-known upstarts or major-label stars? “The new radio,” as some have gushed, or just the latest repackaging of old formats? How it all shakes out could have long-term ramifications for the music-listening and music-making alike.

Embers of sunlight glint over downtown Des Moines’ modest skyline as I walk toward the YMCA at the end of instructor Sara Kapfer-Croskey’s early-bird 5 a.m. step class. The 44-year-old also leads spinning and body pump workouts, and she knows how music can make or break an exercise session. “If a bad song comes on that’s not the right beats per minute, it just feels like your whole class falls,” she tells me.

Kapfer-Croskey puts great care into her song selections, compiling them from her CD collection as well as the thousands of MP3s her husband has dropped into her iTunes. When making a playlist for a class, she tries to span all genres and decades while making connections between lyrics and specific exercise moves. “If we’re doing squats, I like a song that says something about your booty in it,” she says. Not everything is so intuitive, though, and certain workout music that she herself enjoys might not translate to a group. “I tend to lean toward the heavy metal side of things when I’m exercising,” she adds.

The strong connection between music and the gym isn’t lost on streaming companies. Working out and playlists are joined, if not at the hip, then at the foot, and the link between the two is emblematic of playlists’ importance more broadly. In May, Spotify introduced its Running feature, which is designed to detect and complement a user’s running pace. Google Play Music offers a Working Out category of playlists, with subcategories from “Hillbilly Bodybuilding” to “Girl Hold My Earrings”. For a while, Kapfer-Croskey tried Pandora, “but I got annoyed because there were so many songs that I didn’t like,” she says.

Kapfer-Croskey isn’t alone in standing on both sides of the streaming-versus-buying divide. On-demand streaming by U.S. listeners was up 92% through the first half of 2015, with more than 135 billion streams, according to Nielsen Music. Still, in 2014, streaming made up just 27% of industry revenues, compared with 37% for digital downloads and 32% for physical sales, according to the Recording Industry Association of America. So while streaming is most definitely the future, the future hasn’t quite gotten here yet.

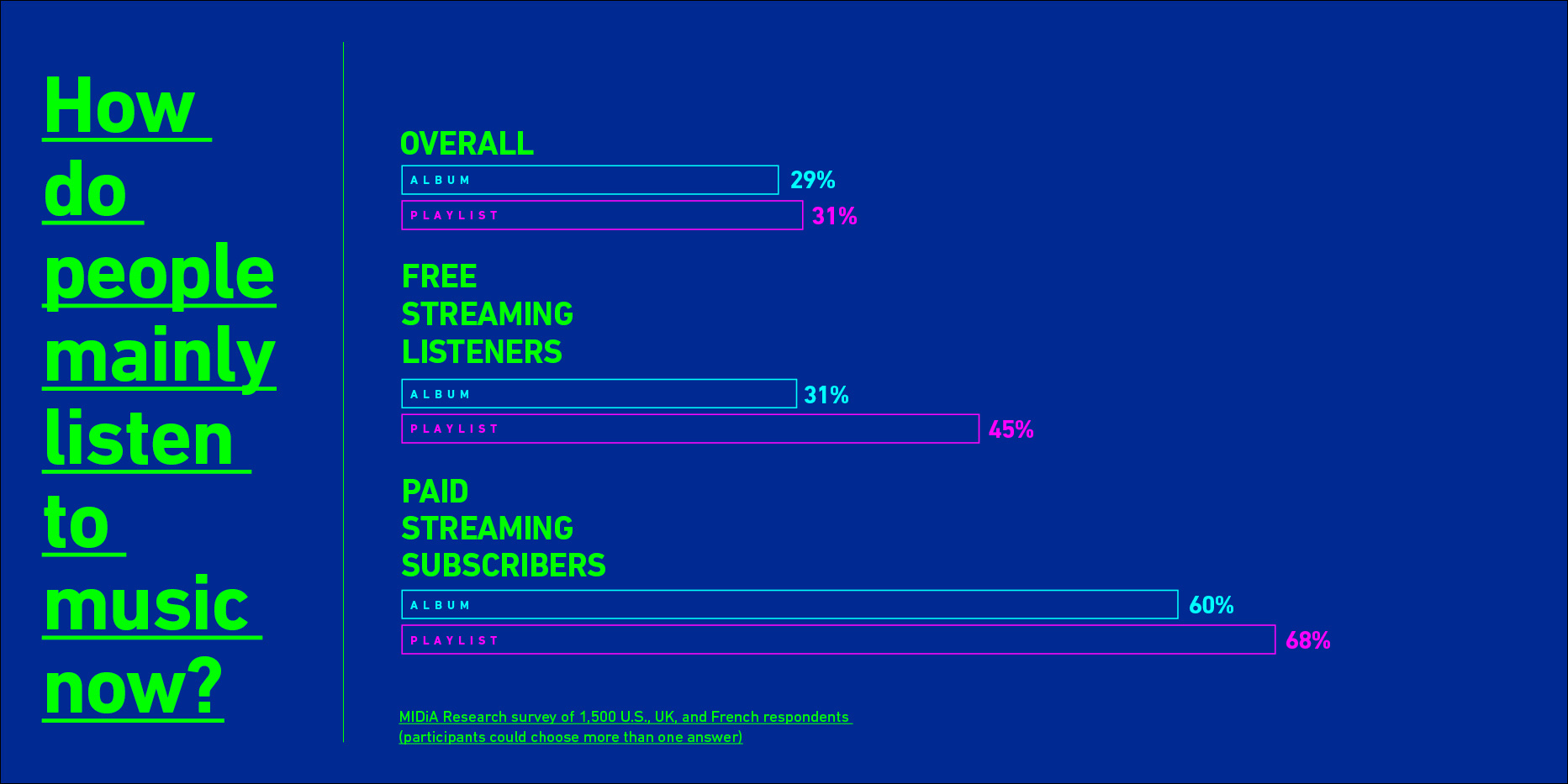

Within streaming, there’s a similar crossover between playlists and traditional albums. “We are absolutely in a world where two consumption patterns are coexisting,” says Mark Mulligan, founder of London-based MIDiA Research, a digital-music market research firm. In early June, Mulligan surveyed 1,500 U.S., UK, and French respondents. Overall, 29% said they mainly listen to albums, while 31% said they mainly listen to playlists. Among the generally younger and more pop-oriented participants who listen to free streaming music, 45% said they mainly listen to playlists, and 31% said they mainly listen to albums. As for paid subscribers, 60% said they mainly listen to albums, while 68% said they mainly listen to playlists (participants could choose more than one answer).

“This is a generational change,” Mulligan says. “We’re at a crossroads, but it’s not a crossroads where any direction is going to be taken immediately. It’s like the emergence of the car—the railroad business didn’t disappear overnight.”

Playlists, too, are hurtling into the future without completely losing sight of the past. The seeds for playlists as they exist now were sown by the likes of Napster and then iTunes, which liberated songs from albums and made it easier to enjoy a broader array of music. When streaming services came along, the divide was initially between the “lean back” method of online radio provider Pandora and the “lean forward” tack of Spotify and its ilk, but the lean-forward players eventually added their own radio-like features, too.

More recently, the pendulum swung toward adding a human touch to the process of music discovery. Now, one vision of playlists’ future has moved beyond recommending music based on what people like already and toward songs tailored to each user’s exact present circumstances. And I mean exact: “Songs to Sing in the Shower”. “Country Songs About Fishin’”. “Coffee-Break Songs for People Who Are Deep-House Fans on Wednesdays But Prefer Grindcore on Thursdays.” (OK, I made up that last one, but it doesn’t seem that hard to imagine at this point.)

Doug Ford, director of music programming at Spotify, talks excitedly about “surfacing the best content for the right moment.” According to Google Play Music product manager Elias Roman, the current state of the art is “less about personalizing existing tastes and more about, ‘What would a DJ that was following me do?’” At Apple Music, Trent Reznor channels his employer’s best-not-first branding. “Ultimate mixtapes by people who know how to make them,” he summarizes. “You can sense the quality.” Former Pitchfork editor-in-chief Scott Plagenhoef, who runs music programming and editorial across Apple Music, says of the service’s own set of activity-based playlists, “The experience of curating around what you’re doing is what’s important, the way a club DJ would.”

Each streaming service emphasizes a slightly different relationship between human and artificial intelligence. Spotify’s Ford takes pride in how his team combines algorithms and human oversight, filtering through billions of hours of listening data to deliver the right “moods and moments” from more than 1.5 billion playlists, many of which are user-generated. “Sometimes it feels like ‘algorithm’ is a nasty word, and it’s not,” he tells me. “It’s an incredibly powerful word.”

Jessica Suarez, Google’s lead streaming music editor (and a former Pitchfork associate editor), stresses that the service is editorial-driven and that algorithms come into play in how playlists reach people, but not in choosing songs. Apple’s Plagenhoef similarly says no algorithms are used until the distribution, rather than the construction, of the service’s playlists. “Both our radio product and our playlists are all completely hand-picked,” he tells me. (Pitchfork is one of Apple Music’s curation partners.)

There’s little doubt that when it comes to playlists, companies are putting their money where the pundits’ mouths are. Google’s Roman and Suarez joined the online search giant after it bought Songza, the playlist-making startup he co-founded; Apple Music stems from its parent company’s $3 billion purchase of Beats Electronics; Warner Music Group bought Playlists.net, an aggregator of Spotify playlists; Rdio acquired music recommendation platform TastemakerX; and 8tracks, a site that has been streaming user-curated playlists since 2008, recently announced $2.5 million in debt financing from Silicon Valley Bank.

Companies have also been betting big on startups that analyze data about people’s listening habits. This year, Pandora bought Next Big Sound and Apple bought Semetric, while in 2014, Spotify bought The Echo Nest. Financial terms of the deals aren’t disclosed, but the pattern—investment in services meant to help listeners find music they might like—is clear.

It’s not quite dark yet at the outdoor bar adjacent to Vaudeville Mews, a 230-capacity venue near my home in Des Moines. T.J. Wood, who tends bar here and a couple of doors down at The Lift, is blasting Jon Spencer Blues Explosion’s 1999 release Xtra-Acme USA, which he calls “my idea of a summer record.” Later, at my suggestion, we’ll listen to a few songs from retro soul singer Leon Bridges’ new debut, Coming Home, before Wood puts on a crowdsourced two-hour mix of summer songs from a group he’s part of on the streaming site Mixcloud. “I love hearing someone’s playlists,” he says.

If there’s anyone I trust to tell me about the usefulness of playlists, it’s Wood—my phone’s Notes app tends to add a band name or two with each of our conversations. When he’s really busy at the bar, Wood creates artist-based custom radio stations using his Microsoft Xbox Music subscription. On slow days, he seeks out new music, maybe spending time listening to a college radio station.

He is perhaps the most musically evangelical of The Lift’s staff of bartenders, each of whom brings a distinctive soundtrack on the nights they’re working. “When they started The Lift, they didn’t want to have a jukebox—you just had a bartender playing cool music, and that’s it,” the 32-year-old says. “Playlists aren’t a new thing. It’s just what they’ve been called now because it’s in the user’s hands so much more than it ever was.”

Along with professional curation, user-generated playlists are another central feature of the current streaming landscape. Half of Spotify users stream from other users’ playlists at least monthly, according to the company. To get a sense for what makes these amateur playlist makers tick, I got in touch with a few of the Swedish streaming giant’s power users, who ended up being as different and similar as any music fans.

There’s Jonathan Good, a 37-year-old business manager near Glasgow who has about 2,000 followers on Spotify and says his “obsession” started after a positive review for one of his playlists on another site. One of his most successful playlists, “If Darth Was a DJ”, is based on what he imagined the Star Wars villain would play behind the decks. “I’ve always enjoyed sharing my musical discoveries, and Spotify gives me the ability to do that on a larger scale,” Good tells me in an email. “Playlists are now the way we listen to music, and I can see a time coming when the playlist creator becomes just as important an element in the process as the artists being featured.”

Then there’s Soundofus, aka Gerard, a retired school director from the suburbs of Paris with almost 20,000 Spotify followers who asks me not to publish his age or full name (but says he has seen the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and the Who all perform live). He runs a music review website and got a big break when a playlist he researched and compiled with songs from the 2012 Summer Olympics in London ended up going viral.

Diestro, aka Cristian Garcia, an unemployed 25-year-old from southern Spain with 18,000 followers, says he made his first playlist to organize music that he likes, such as Dire Straits and Queen, but since then has made more than 200 more across different genres and styles. He tells me in an email that while Apple and others hire paid playlist makers, it’s amateurs like him that are often more effective. He hopes more services will take Spotify’s lead in empowering its users and, at the same time, hopes to one day work in a job “related with music, something that I enjoy every minute of my life.”

The line between amateurs and professionals is another area of overlap where playlists are concerned. Stephen Thomas Erlewine, senior editor for pop music at AllMusic, has more than 1,000 followers on Spotify in his own right, and I’ve heard nothing but high praise for his “STE Ultimate Yacht Rock” playlist, which itself has around 400 followers. He points out that plenty of user-generated playlists are simply the tracklists from an album, further blurring distinctions. “It’s a seemingly simple subject that’s actually quite complex,” Erlewine says of playlists.

For all the nuance required in talking about playlists, their rise also brings up an important question for the future of music culture. For one, artists will have more of an incentive to experiment with other formats beyond the conventional album, though hardly anyone expects the album itself to fade away as a promotional or artistic statement anytime soon. Diplo may have hinted in that direction in discussing the brief, 32-minute length of Major Lazer’s new album Peace Is the Mission, which USA Today reported was geared toward young fans’ attention spans. MIDiA Research’s Mulligan says, “There’s a huge amount that can be done that hasn’t even started yet in filling the album-shaped hole that will evolve in the future of streaming.”

From a listening standpoint, if fans develop fewer strong attachments to individual artists, the shift toward playlisting could eventually lead to what Mulligan has called “a collapse in arena and stadium-sized heritage live acts.” Already, the average age of UK festival headliners is going up, according to a Spotify analysis reported by The Economist.

Then again, if playlist-ification means fewer traditional superstars, advocates have an inkling it could also help shed light on artists who weren’t previously famous. Two of the biggest success stories from Spotify’s playlists so far are Lorde, who famously appeared on Napster co-founder Sean Parker’s Hipster International playlist before she became an international sensation, and Hozier, who garnered 46% of his first plays on Spotify from the service’s curated playlists last year. A still more serendipitous example may be Jamaican singer OMI’s “Cheerleader”, a three-year-old reggae song that recently hit #1 on the U.S. Hot 100 as a trumpet-sprinkled tropical-house remix. Its improbable, Spotify-aided invasion followed a trail blazed by Dutch singer Mr Probz’s “Waves”, a self-released track that was a hit in Europe before an uptempo remix helped it to reach #14 on the Hot 100. For all of these songs, playlists were crucial: Spotify director of economics Will Page has written that “curated playlists carried Mr Probz across borders that he otherwise would not have crossed.”

Spotify’s Ford says, “The beautiful thing for me is that every song stands a chance to make its way onto a playlist and stand on its own merit.” Google’s Jessica Suarez tells me about a playlist called “Sun-Streaming”, which includes songs by both indie faves Atlas Sound as well as goliaths like Arcade Fire: “There’s bands on there that had trouble building up a physical audience, but they do just as well on that playlist as bands that sell out stadiums, because we picked out the best song from their album.” Another widely discussed risk is that playlists could just be pushing what the labels want us to hear. But as with any editorial venture, credibility comes down to keeping an audience’s trust. Google’s Roman tells me, “If Jessica doesn’t like it, it’s not happening.”

Going forward, one question mark will be how well playlists a user makes for personal use on one service can be transferred to another, especially if competition between the services increases. Tidal’s website offers a link to Soundiiz, one of the third-party sites that converts playlists from one streaming company to another. “We are like a bank—not for money, but for playlists,” says Thomas Magnano, who co-founded the French startup. As Magnano tells it, streaming music is like renting a house, and exporting playlists is like changing homes—meaning that some huge furniture can’t always survive the trip.

Also on the user-constructed side, a potential benefit of playlists could turn out to be their use in advocacy. Feminist Music Geek blogger Alyxandra Vesey, a University of Wisconsin-Madison media scholar, tells me playlists allow feminist communities to promote their work but also bring that work into meaningful context. “When you put TLC’s ‘No Scrubs’ and Destiny’s Child’s ‘Bugaboo’ in dialogue with other songs that may not explicitly be dealing with harassment, they can be contextualized,” she says. Outside of feminism, playlists have also popped up around causes such as the Black Lives Matter civil-rights protests after last summer’s police-involved killings of African-Americans.

Tech and music are two business hardly known for being immune to trends, and the playlist push has been met with mixed responses from the news media. “I worry I’m hiking into an unhappy valley of music streaming, where I like more, but love less,” noted The Wall Street Journal’s Geoffrey A. Fowler recently. Pitchfork contributor Jill Mapes wrote for NPR: “I find myself constantly fighting the inclination to switch the song when I’m using one of these recommenders, be it Pandora, Spotify Radio, Beats Music, or Rdio’s You FM. It all sounds so … same-y.” The New York Times’ Ben Ratliff, after praising playlists created for Tidal by artists including Beyoncé and Usher, called for streaming services to hire “a single person of distinction” and empower that person to pick songs. “That’s where discovery will always lie: In the suggestions of actual human beings,” Ratliff wrote. “Divisions by genre, format, or mood may be arbitrary. Individual people never are.”

Like many music lovers, I’m of two minds when it comes to today’s prominence of playlists. On one hand, I feel like streaming playlists have been a part of my life since the middle-school mixtapes that I can no longer find but still attempt to reassemble virtually. On the other hand, I’m less excited about trying new technology than I am about trying new music, so I’m more likely to trust in a friend or a college radio DJ: “a single person of distinction.”

I’ve been listening more to playlists lately though, partly in a professional capacity and partly because listening to a list of familiar songs as my wife steers our family home on a sweltering Friday night seems like a good idea for keeping everyone awake (even if that means staying awake to a familiar song I thought I never wanted to hear again… OK, fine, it was Matchbox Twenty’s “Push”). For playlists, for curation, it seems not only natural, but essential to take my time deciding if there’s really wheat within all this chaff.

“Each user is also curating the entire history of music,” Apple’s Plagenhoef tells me. “They’re naturally doing that through the limitlessness of choice and the limitlessness of being able to manipulate that choice. Some kind of notion of a playlist is the natural organizing principle and delivery system for it.”

If playlists are how the entire history of music can most naturally be organized, then that history, too, appears to be at a stage of transition. According to Nielsen report released in June, 93% of adults still listen to traditional AM/FM radio at least once a week, and a slightly earlier report found that “radio remains the top source for music discovery.” Is the “new radio” still just radio?

Terrestrial broadcasters and the new online playlisters will no doubt continue to coexist, but the industry is wagering that younger listeners will increasingly curate music’s history more directly. They’ll pick from among the manifold variety of playlists, some curated by professionals, others selected by users like themselves. And they’ll listen both in the places long home to older types of playlists, such as gyms and bars, as well as newer locales enabled by the mobility of smartphones.

But there will be access to more “ultimate mixtapes,” to use Reznor’s phrase, than before, with input from more people: exercise instructors and amateur streamers a world away, along with college radio DJs, Top 40 playlisters, and, yes, Beyoncé. The promise is that, in this new pocket library of nearly infinite playlists, we all, looking together, might find those particular records that mean so much.

And what if most listeners end up finding a bunch of music they “like” rather than “love”—the same old musical comfort food in snazzy new packages? Albums might change their shape, a good festival headliner might get harder to find, but that still wouldn’t be the worst possibility—for music as mass culture, in fact, it might be the same as it ever was. Either way, while “the unhappy valley of music streaming” sure sounds like a bummer of a place, it doesn’t have to be real.

A Google search for “songs about playlists” still comes up empty for me as of press time, but there are countless tracks about predecessors like radio, DJs, and mixtapes. One from a band on Apple Music’s “Artists John Peel Helped Make Famous” playlist is the Smiths’ 1986 indie-pop classic “Panic”, with its sneering refrain, “Hang the blessed DJ, because the music that they constantly play, it says nothing to me about my life.” But today’s DJs know much more about our lives—including our tastes, activities, and circumstances—than ever before. Their necks ought to be a bit more precious now.

Additional reporting by Evan Minsker