A face to remember

MIT researchers’ feature tuning algorithm can make your profile photo more memorable

Sarah Lewin • April 17, 2014

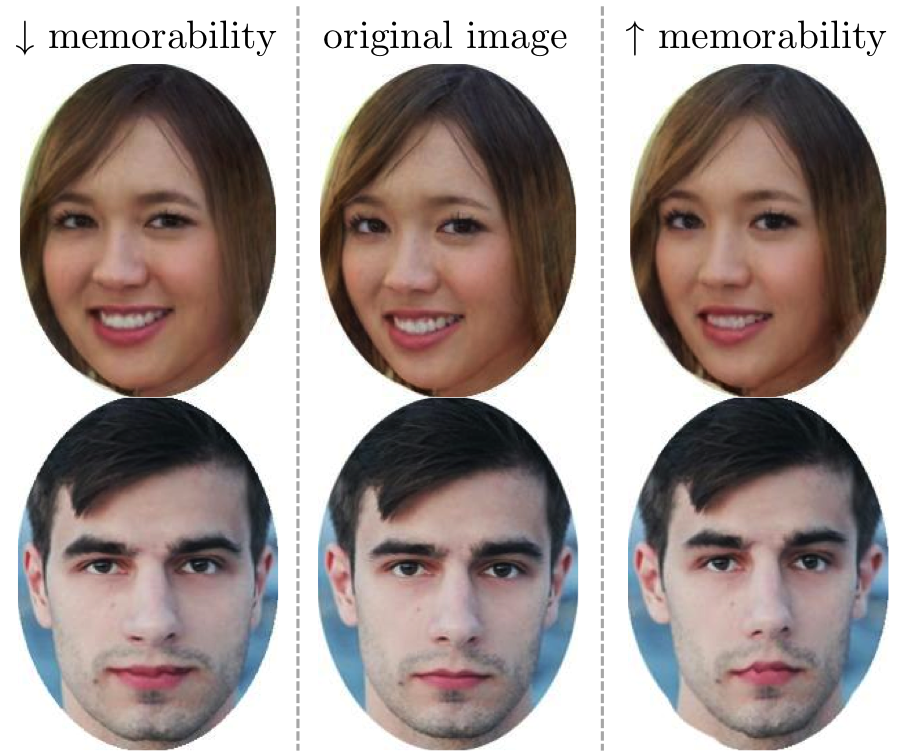

A thousand tiny changes were made to these portraits to make them more or less memorable while keeping their resemblance to the original. [Image credit: Aditya Khosla]

Standing out in a crowd — and particularly, the crowded world of social media — may become a little easier as MIT researchers develop a clever way to tweak profile photos to play up a person’s most memorable facial features.

Aditya Khosla and others at MIT have found a way to make photographs of faces more memorable or more forgettable, opening new doors in the understanding of memory. The process was detailed in work presented at the International Conference on Computer Vision in Sydney in December 2013 and earned Khosla a Facebook Graduate Fellowship for further research. According to the researchers, such “feature tuning” — which could be extended from memorability to other qualities, like confidence or trustworthiness — has the potential to change everything from one’s profile photo on Facebook to online dating to political campaigns and advertising strategies.

Do you remember me?

In Khosla’s first few weeks as a graduate student at MIT, the talk on campus was about a recently published paper that brought psychology together with machine learning — training a computer to identify patterns in data. Aude Oliva, a researcher with MIT’s computer vision and graphics group, explored what makes images memorable and came to an unlikely conclusion.

“They found that all images are actually not created equal,” says Khosla. “There are some that just stick in our mind: Memorability is an intrinsic property of an image.”

Oliva and her colleagues noticed that although people couldn’t guess which pictures would be memorable in an online test, certain images were consistently remembered better or worse. Their next line of research was to figure out what in a photo of a face makes it stick, or fade away. By inputting 2,222 photos and their memorability scores from the online test as training data, Oliva’s group was able to teach a computer to predict the memorability of photos it hadn’t seen before.

The photos that ranked highest on memorability didn’t have greater beauty, a bigger smile, a special gleam in the eye or a certain shape of the jaw. Rather, the computer was picking up on a multitude of tiny details and quirks that contributed to memorability but would be impossible to find and define on their own. There were no big distinct trends — instead, a thousand tiny tweaks, statistically tied to the memorability of the photos in the study.

Machine learning often follows this process, although it hadn’t been used for memorability before, says Gregory Hager, a computer vision researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

“By and large, these sorts of approaches don’t give you explanatory power — they give you a result,” says Hager. “So you get an algorithm which might perform quite well, but you can’t articulate necessarily why it does that. It’s basically a black box that goes from measurements to output.” Knowing that something is measurable is the first step; after that, it’s possible to train a computer to look for it and put it to work.

Changing it up

Intrigued by the idea that small changes could lead to big differences in memorability, Khosla brought his idea to Oliva: If a photo is memorable because of differences in a few pixels, could changing those pixels change the memorability?

Khosla and his colleagues set out to create an algorithm to capture that memorability and impart it to other photographs. The researchers focused on faces because small changes could have a large effect while leaving the photo recognizable.

The team’s program first makes a chain of small, random changes to a photo, creating a slew of photos with only slight differences from the original. It gives each new image a score, detracting points if the changes affect attributes like emotion or attractiveness or if the face begins to look different from the original; it awards points if the photograph becomes more memorable. Meticulously measuring 10,000 randomly-changed versions, the program pinpoints the highest scorer: a more memorable face that still looks like the subject. Then it starts the process again and alters that picture, slowly building up to the best possible modifications. It can also go the other way — toward a less memorable photograph. As Khosla worked with the algorithm, he tried tuning other attributes besides memorability — the algorithm could just as easily tune things like attractiveness and friendliness, and it was easier to see at a glance if it was working.

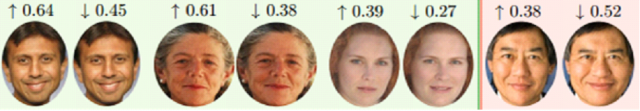

Tuning other features like age, attractiveness and friendliness led to easier-to-identify success cases. [Image credit: Aditya Khosla]

Researchers tested the newly changed images on participants using an online memory game. Three out of four images they altered to be more or less memorable produced the desired reaction in real people.

The results are the first of their kind. Hager, the computer vision researcher, says that while the data collection process was similar to other machine learning work, combining that algorithm with an optimization process is new.

The changes to faces in the green box succeeded in changing memorability as planned, and those in the red box failed. The arrow indicates whether memorability was expected to increase or decrease, and the number is the memorability score when viewed by actual humans. [Image credit: Aditya Khosla]

Branching out

Algorithm in hand, Khosla will soon turn his sights to tuning other, more complicated features of a photo using the same type of data gathered from online surveys. Then the possibilities are endless, he says.

“Make me look more confident, for a dating website,” says Khosla. “Make me look more trustworthy, for a politician’s photo in a newspaper. There’s more than just the simple attributes that people have studied.”

Oliva says it’s important to remember that the measurements and alterations refer to the photograph, not the face. “It’s not necessarily that your face itself is memorable or forgettable,” she says, “it’s actually the attitude you have. The light coming from your face. Everyone, depending on how the photo was taken, can look more average or more distinctive.” She suggests that the process could be used to choose photos with better features, rather than just to alter them after the fact.

According to Adam Glenn, a journalist and digital media consultant, this kind of feature tuning — while technically impressive — fits with the way people currently use social media.

“I really see no difference between altering your image in this way and fudging your age on a dating site or polishing your resume to focus on your skills in a positive light,” he says. “It’s like virtual makeup, a way of presenting yourself.”

Glenn anticipates that the process could be very popular, especially when used with apps that rely on an image to draw you to a purchase or a romance.

Looking forward

In broader terms, the MIT researchers are already thinking about future uses. The benefits for advertising are clear to Khosla.

“If we could pick or modify images to make them extremely memorable, we’d just have to show them once,” he says, as opposed to over and over again on billboards, in magazines and on TV. “You don’t really have a choice but to store the information because that’s how we are all programmed.” Changing photos of products or packaging in smart ways could create an instant connection.

He’s quick to add that there are more meaningful uses for the memory research as well. Researchers might develop a model tailored to help people who are unable to recognize faces, for instance, or educators could make more memorable charts and infographics for easier learning. Oliva’s group has already published an analysis of what makes infographics memorable and what parts of them people store in memory, as well as looking into the memorability of particular words.

Final form

Phillip Isola, a graduate student who works with Oliva on memorability, put his own image through the algorithm near the beginning of the project.

“If I were confident that it was really preserving my identity,” he says, “not modifying who I am but just making the best angle on me, then it’d be pretty nice to use for a profile pic.”

Of course, because it was an early version of the algorithm, it didn’t go perfectly: the computer had tried to insert teeth into his closed-mouth smile.

Khosla is confident that the technology will be useable by the mainstream soon – his next goal is to cut down on the time the algorithm takes and to reduce errors and artifacts introduced in the process. He says smoothing out the process only a matter of tinkering. Then and only then will it reach its final and inevitable form: the smartphone app.