What will be left of the union flag?

Precisely what would happen to the flag in the event of a yes vote is not clear. Constitutional experts suggest there would not necessarily be any requirement for the remainder of the UK to abandon the current flag, although Lord West, deputy chairman of the parliamentary flags and heraldry committee, has suggested it would be “nonsense” to imagine the St Andrew’s blue could remain in the flag.

Downing Street insists it has made no preparations for a yes vote, not even on the question of the national symbol. “We haven’t made any contingency plans for that,” a spokesman said on Monday.

The College of Arms, the official register for flags, coats of arms and pedigrees for the crown, which was responsible for the design of the current flag in 1606, similarly declined to be drawn ahead of the vote.

The York Herald, Peter O’Donoghue, said that in the event of such a dramatic change, “I’m sure it’s something that would be discussed by the Garter King of Arms [the most senior officer at the college] with the government and the palace”.

Pressed over whose final responsibility it would be to choose the design, however, he acknowledged it was something of a grey area: there was no automatic legal bar on the current red, white and blue flag, and no established mechanism for changing it. It is not, after all, something that comes up very often.

Part of the problem, according to Charles Ashburner, chief executive of the Flag Institute, is that the flag “fell into use” rather than ever being formally adopted, so “nobody controls the union flag”. Successive governments, he said, declined to sort out the constitutional anomaly, meaning that “potentially on Friday morning in the post apocalyptic nightmare that Scotland is going to have after a yes vote, all these questions are going to come home to roost”.

Despite leading “the world’s leading research and documentation centre for flags and flag information”, Ashburner describes the constitutional confusion surrounding the current union jack – which was amended in 1801 at the College of Arms to incorporate the red diagonals of the Irish cross of St Patrick – as “a dog’s dinner”. Wales, he notes, is not currently represented at all.

According to some constitutional experts, because the current flag technically represents a union of the crowns not the nations, and the Queen would be likely to remain monarch of an independent Scotland, there is no legal or constitutional reason to stop flying the current flag south of the border.

Ashburner thinks it more likely that Britain would eventually be represented by two flags: the current union jack abroad, and another which “represents the rest of the UK as it then exists”.

“If Scotland is not in the UK any more, can it really be OK that Wales is not represented in the flag and Scotland is?” Prepare for the red, white and green? Esther Addley

What will happen to Gretna Green?

The Scottish border town famous for hosting “runaway weddings” will survive. Currently it’s not very difficult for foreign nationals to get married there and that is unlikely to change. Just like Scots, foreigners must give the registrar at least 15 days’ written notice of a marriage, ideally four weeks. The only difference is they have to provide a “certificate of no impediment to marriage” proving they are not a bigamist, for example, which is easy to obtain in most European countries. At the moment, anyone resident in the UK for at least two years prior to the wedding doesn’t need this certificate.

As with everything in a post-independence world, no one really knows what will happen. But as Alan Air, spokesman for Gretna Green’s Famous Blacksmith Shop, puts it: “I can’t see any government wanting to harm an industry which is so important to a town.”

Last year 3,620 marriages were registered in Gretna Green, with most brides and grooms not being Scottish – a tradition begun in 1754 when Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act introduced a minimum marital age of 21 without parental consent in England, which did not apply to Scotland. Helen Pidd

Will I need a passport?

The notion of passport checks at the Scottish-English border seems almost ludicrous. A deal to keep an independent Scotland within the common travel area – as Ireland is – looks to be the most straightforward solution. But immigration could be a real obstacle to such a political settlement. Scotland is likely to take a more relaxed approach to immigration, which a Westminster government could object to, meaning it is not a foregone conclusion that the border would remain passport free. Claire Phipps

What would the rest of Britain be called?

The “United Kingdom of Great Britain” was created by the 1706 treaty of union, and the 1707 Act of Union the following year, as England and Scotland were merged. A swaggering Britain, then very much on the rise, was too confident to waste time fretting about its brand name: when Ireland was roped in, in 1800, “and Ireland” was crudely appended as an afterthought, just as “and Wales” had sometimes been tacked on to the name of the English kingdom of old.

But having already lost an empire, if the Britain of today were to lose a third of its landmass there would be considerably more introspection. Residual UK – or rUK – has gained some currency as a potential name, though it would only highlight the state in which it had been left. An obvious acronym problem makes Former UK even worse.

As panicked politicians scramble to propose new devolution settlements, perhaps they should give up on the whole idea of a single national brand, and dig back into history’s back-pages to come up with splendid placenames, such as Mercia, Northumbria, Wessex and even Danelaw, each of which could sit in rough equality alongside Wales and Northern Ireland under some messily redesigned flag. Tom Clark

If Scotland does secede, can the rest of us stay on British Summer Time?

The debate about how to set our clocks has been going on since standardised time was introduced with the expansion of the railways in the 1840s. Campaign groups advocate keeping BST over the winter months and putting the clocks forward a further hour during summer, giving the UK the same time zone as much of central Europe. Supporters of this idea say it would reduce energy consumption, increase economic productivity and reduce accidents.

Previous attempts to change UK time have been opposed in part because of the effect it would have on areas of Scotland and Northern Ireland, where the sun would rise as late as 10am and children would have to walk to school in darkness.

In the past the prime minister, David Cameron, has seemed sympathetic to the idea of extending BST and, with Scottish voters out of the picture, there would be less opposition to Westminster giving the issue serious consideration. Frances Perraudin

Will there be a house price boom on the English side of the border?

Who knows? Andrew Low, a valuer at H&H King estate agents in Carlisle, which does business on both sides of the border, says he anticipates Carlisle benefitting from an independent Scotland.

“We will be the nearest economic centre to Scotland, with the rail and motorway infrastructure, so almost perversely we could see a sales increase as firms relocate to Carlisle so that they can stay English-based while doing business with Scotland,” he said.

Over the last year people had been “holding their breath” and waiting to see what happened before buying or selling. “There are people who would like to live over the border for the benefits which come with living in Scotland – free university places etc – but they want to wait and see if those benefits will change as a result of independence.”

A lot of uncertainty surrounds the outcome, he said.

“I don’t think there will be a new Hadrian’s Wall or barbed wire and search towers on the border, but if there is a new currency it will undoubtedly affect cross-border sales. Right now we have three sales going through in Scotland. That would be more complicated with a different currency. Perhaps we’d have to think about opening a Scottish branch.” Helen Pidd

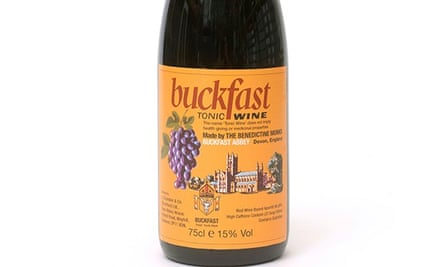

What will happen to Buckfast?

The first time somebody told me they were worried that Buckfast would not be available in an independent Scotland, I thought they were joking. The availability of the notorious tonic wine, brewed by Benedictine monks in Devon, certainly wasn’t something I’d heard the no campaign include in their ever-expanding list of dire consequences following a yes vote.

But a handful of folk have mentioned it to me now, and it seems there are genuine concerns about future access to this highly caffeinated alcoholic drink, or Wreck the Hoose Juice, which is mentioned as a contributing factor in thousands of violent crimes every year in Strathclyde alone.

The company that distributes Buckfast says it has been fielding calls about it for months, but remains neutral on the referendum. But it seems unlikely that it would prove any more difficult to import Buckfast to an independent Scotland than, say, French-made champagne, though whether its price would rise to match Moet is another matter. Libby Brooks

This article was amended on 16 September to correct a quote by Charles Ashburner about constitutional confusion around the union jack.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion