From the flicker of heat in pepperoncini to the incendiary burn of the Carolina Reaper, the chilli has conquered the world. These pungent pods are now the most widely grown spice crop of all. But, in recent years, the medical profession has become increasingly interested in the chemical ingredient of its trademark heat, with one recent study even suggesting the spice may also offer a way to help conquer the ravages of old age.

The chilli pepper is the fruit of plants from the genus Capsicum, a member of the nightshade family that includes tomatoes, potatoes and eggplants. The compound that makes them so spicy is known as capsaicin, a nitrogen-containing lipid related to the active principle in vanilla (vanillin) and has the same effect on our pain receptors as heat.

The blowtorch effect of a Scotch Bonnet arises because pain-sensitive nerves in the mouth, notably the tongue, harbour a receptor protein known as TRPV1. When this receptor is activated by capsaicin, it produces the sensation of scalding heat. Strictly speaking, however, chilli does not really taste hot. Our taste buds respond to salt, sweet, sour, bitter and umami, while chilli offers the sensation of heat. That's why, when exiting the body, capsaicin has a second opportunity to burn, even though there are no taste buds at its point of departure.

While capsaicin might set our mouth on fire, it also leads blood vessels to relax, so it could help people with high blood pressure. Prolonged activation of TRPV1 on the membranes of pain and heat-sensing nerve cells also depletes substance P, one of the body's messenger chemicals. That is why the compound that puts the fire in jalapeños is used as an analgesic in ointments, nasal sprays and patches to relieve minor aches and pains, and the itching of psoriasis.

Now a study by Andrew Dillin of the University of California, Berkeley, suggested this analgesic effect could have a yet more profound impact on humanity. He explained how as humans age they report a higher incidence of pain, suggesting that pain might drive the ageing process and, indeed, his team found that mice genetically manipulated to lack TRPV1 lived on average about 14% longer than normal mice and, importantly, without apparent complications.

Blocking the pain receptor not only extends lifespan, it also gave the mice a more youthful metabolism, including an improved insulin response that allows them to deal better with high blood sugar. "Pharmacological manipulation of TRPV1 may improve metabolic health and longevity," Dillin says.

But, of course, chilli offers another way to achieve the same end because constant activation of the TRPV1 receptor results in death of its host nerve cell, mimicking the loss of TRPV1 that extended lifespan. Eating a diet rich in capsaicin might, he says, "help prevent metabolic decline with age and lead to increased longevity in humans".

There are caveats, of course. Mice have enjoyed many advanced therapies that have not translated to people. And to enjoy the health benefits might require the kind of heroic chilli consumption that would daunt even the most hard core "heat geek". Still, Dillin points out that diets which are rich in capsaicin correlate with a lower incidence of diabetes and metabolic problems in people.

All the while, other research has shed light on this spicy story of global warming, one that speaks volumes, not just about our taste and health but psychology too.

Normally a plant creates fruit in order to entice animals to eat and disperse its seeds, so it was puzzling that a fruit evolved to be painfully hot. To investigate, Joshua Tewksbury of the University of Washington, with Douglas Levey of the University of Florida, and colleagues studied chillies that grow in the Bolivian wild and found a correlation between high capsaicin levels and low seed mortality, particularly in moist conditions.

It seems that evolution smiled on capsaicin because it slows microbial growth and protects against damaging fungi that invade the fruits through wounds left by insects. Plants that produced hot chillies had seeds with thin coats, a presumed consequence of sacrificing the production of lignin, a complex molecule that forms the protective seed coat, in favour of more capsaicin.

Capsaicin deters mammals, such as raccoons, foxes and mice which, having molars, kill seeds when they chew the fruit. However, birds lack the right receptors. They will happily eat the hottest of hot chilli peppers (which is why some varieties are popularly known as "bird peppers") and gobble seeds whole only to deposit them further afield, where young chillies can grow with less competition.

In coming months, festivals in Espelette in the Basque country, Tampere in Finland, Santa Fe in the United States and beyond will celebrate chilli. So why do we like them so much?

One clue emerged in 1998, when Jennifer Billing and Paul W Sherman published a study in The Quarterly Review of Biology in which they surveyed 4,578 recipes from 93 cookbooks on meat-based cuisines from 36 countries. Countries with hotter climates used chilli and spices more frequently than countries with cooler climates. This makes sense since bacteria grow faster in warmer areas and, as Sherman points out, chilli is one of many spices that are antibacterial. A follow-up study by Sherman, this time with Geoffrey A Hash, studied 2,129 vegetable-only recipes from 107 cookbooks from 36 countries and found that they relied on fewer spices than meat recipes. The reason? Bacteria do not proliferate as well in vegetables, so adding spices was not as necessary.

Chilli and other spices probably helped to protect our food from microbial attack long before freezers or artificial preservatives. "Before there was refrigeration, it was probably adaptive to eat chillies, particularly in the tropics," Tewksbury commented. "Back then, if you lived in a warm and humid climate, eating could be downright dangerous because everything was packed with microbes, many harmful. People probably added chillies to their stews because spicier stews were less likely to kill them."

But some argue the antimicrobial hypothesis may not be enough to account for the advance of spicy foods in the modern age of refrigeration and preservatives. "I don't think there is actually much evidence for the antimicrobial action of chilli," explains Paul Rozin at the University of Pennsylvania. "People get to like the burn. In fact, the one effect it definitely has is to cause salivation, which lubricates the mouth and facilitates chewing."

Capsaicin causes the body to release painkilling endorphins, which are themselves pleasurable, so he argues that our love of chilli heat may also be a kind of benign masochism. By this he means something seemingly dangerous, such as riding a fairground thrill ride, in the knowledge that it won't do any real harm. Perhaps the adrenalin kick from tackling the scorching heat of a Dorset naga, plus the natural opiates, are an unbeatable combination.

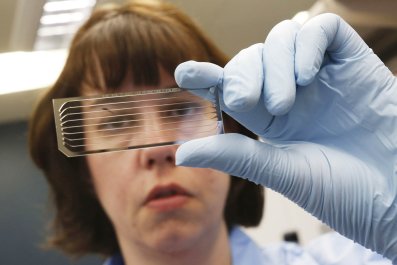

The hotspot where ancient farmers first warmed to the charms of the chilli pepper was revealed by research published this year by an international team led by Paul Gepts at the University of California, Davis. Scientists traditionally pinpoint the origin of domestication by seeking the location with the most diversity of wild relatives, reasoning that the greater the diversity, the longer lineages have been evolving. Genetic evidence, based on 139 wild peppers collected by colleagues Kraig Kraft and José Luna, suggested the hot big bang took place in northeastern Mexico.

Gepts and his colleagues went further, taking into account linguistic evidence uncovered by Cecil Brown of Northern Illinois University and Geo Coppens of CNRS in Montpellier, France. They found that east of the Valley of Tehuacán, where the most ancient remains of the spice have been uncovered, the oldest word for chilli was spoken in Proto-Otomanguean some 6,500 years ago. To bolster this evidence, team members Kraig Kraft, Eike Luedeling, and Robert Hijmans used a mathematical model to predict the most suitable locations for the domesticated pepper.

The origins of domesticated chilli seem to lie in a region of central-east Mexico, in a swathe ranging from southern Puebla and northern Oaxaca to southeastern Veracruz. When it comes to studies of domestication, "this is the first research to integrate multiple lines of evidence," says Gary Nabhan at the University of Arizona, another team member.

We know little about how the Mayans and others in the region used chilli peppers. But research by Terry Powis at Kennesaw State University and colleagues revealed clues in 2,000-year-old pottery samples from a site in southern Mexico, home of the Mixe-Zoquean. They discovered Capsicum residues in a spouted jar, a vessel used for pouring liquid for culinary, pharmaceutical, or ritual uses.

Upon reaching the New World in 1492, Columbus was one of the first Europeans to encounter the fruits of Capsicum, calling them peppers because they had a hot taste dissimilar to anything else he had encountered. Not long after, they were being added to dishes prepared in Spain and Portugal and their use soon spread to Asia and beyond. From familiar curved varieties to those that are pea-shaped, heart-shaped, bumpy and flat – with colours ranging from green to red, orange, purple and black – they're now found in endless cuisines and everything from ready meals to cocktails.

The world's getting hotter.