The Future of Media Will Be Streamed

For music and movies as things you buy and own, this is the beginning of the end.

There was a day when music and movies were a simpler business. Movies made money from tickets. Bands made money from physical albums. Transactions took place between hands or across a register. The business model was a simple point of contact: Drive consumers through the doors.

Today, fewer people are walking through those doors. Music stores are shuttering, devastated by the digitization of music, which sent physical albums into the dustbin of history. Meanwhile, cinema has been eclipsed by TV as the juggernaut of video entertainment. The number of annual movie tickets bought per person has declined from 4.8 to 4 in the last decade. This is what economists call "structural decline," what couch potatoes have called "waiting until it comes out on DVD," and what Hollywood executives call "a reason to pray rather fervently that people will pay more for the 3D version of the fourth sequel of the second reboot of our comic franchise."

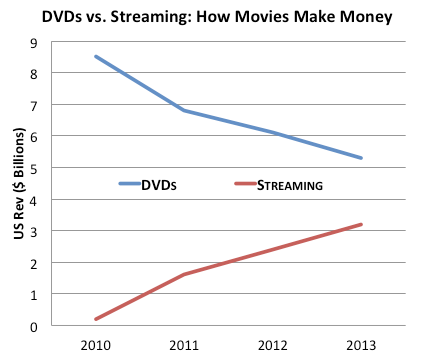

It's ironic, then, that just as the Internet and TV have conspired to devastate the old business models of music and movies, they're also come together to create new business models to save them. A new report from Moffett Nathanson estimates that since 2010, streaming (e.g.: Netflix and Hulu) has gone from zilch to a $3 billion business, while DVDs, which many hoped would rescue the movie industry, have declined sharply in the same period.

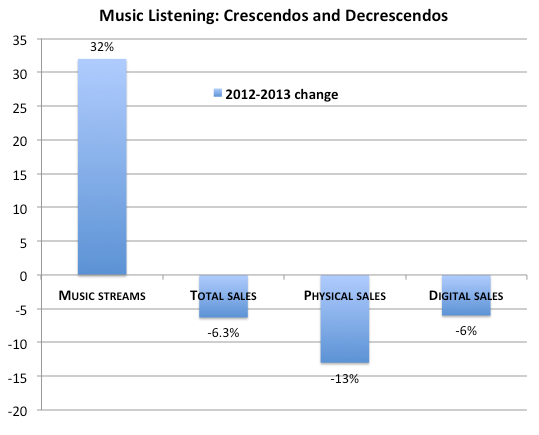

Streaming is coming to the rescue of the music industry, too. Just as DVD sales have wilted after once appearing to be the savior of movies, digital music sales (e.g.: iTunes singles) have started to decline as well. Overall streaming is up 32 percent. Music subscription services like Spotify doubled their listens last year and just became a billion-dollar business.

The upshot is that entertainment industries have, in the last half-century, gone from simple merchants—buy a ticket in this physical store; buy an album in this physical store—to digital cephalopods, sticking their tentacles into a multitude of diverse businesses and adapting surprisingly quickly to consumer habits as we fall in and out of love with different ways of watching video and listening to music.